Murasaki Shikibu’s View of Love|What Quiet Passion Lived Within Her Brush?

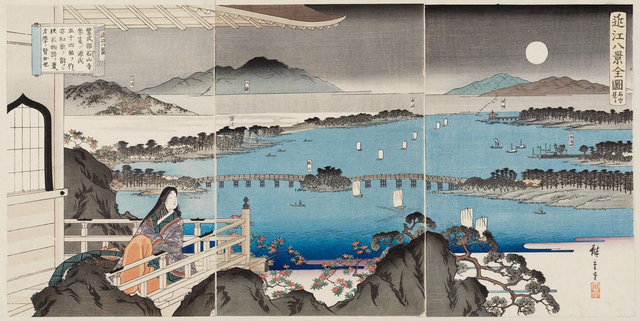

Around the turn of the 11th century, in the middle of the Heian period, poetry and love were woven into the fabric of daily life, like light and shadow dancing together. In this era, one female poet left her name in history through the power of storytelling.

Her Tale of Genji is far more than an elegant court romance.

Desire and loneliness, yearning and vanity, and the unheard voices of women rise from its pages like a wisp of fragrant incense.

But what about her own love—the woman who held the brush?

Did she long to be loved?

Or did she allow her solitude to show only on paper, hidden from all eyes?

Murasaki Shikibu’s view of love, behind her quiet prose, must have burned with fierce intensity.

A Girl’s Gaze

Words Unfolding

Murasaki Shikibu—believed to be named Fujiwara no Kaoruko by birth—spent part of her youth in Echizen Province, having accompanied her father Tametoki on a provincial appointment.

The rugged natural environment and life far from the capital are said to have shaped her sensitivity and honed her powers of observation—and of silent endurance.

At the time, it was rare for women to be fluent in Chinese characters.

Yet she is said to have read the Chinese classics and Buddhist texts at home “of her own accord.”

Upon witnessing this, her father reportedly murmured:

“If only she were a boy…”

No one knows what that remark truly left in her heart.

But throughout her work, we can sense an ever-present tension between regret and pride in being a woman.

Memories of First Love

As a young woman, she was considered eccentric—gifted, but introverted and reserved before entering court life.

And so, it is thought that the first man she gave her heart to may have been someone humble and unaffected by social status or scholarly pride.

Though no solid records remain, there are theories that she once had a brief romance with a low-ranking official in her youth.

His name is lost, but some believe his shadow lingers in her poetry.

One such poem reads:

Not past, not present—none but I could ever see

these sleeves, stained with tears of longing.

Even after love ended, she may have shown her sorrow to no one,

letting it flow silently through her brush.

Life with Her Husband, Fujiwara no Nobutaka

Was Marriage a Refuge of Peace?

Murasaki Shikibu married after the age of 30—a relatively late marriage for the time.

Her husband, Fujiwara no Nobutaka, was a court official over 20 years her senior, introduced through mutual acquaintances.

Their union was not political, but seemingly quiet and gentle, perhaps rooted in a mature, tranquil affection beyond youthful passion.

Nobutaka was a skilled poet himself and one of the rare men who respected and understood her literary talents.

They had one daughter together—Daini no Sanmi, who would also become a celebrated poet.

But Nobutaka soon fell ill and died, ending their marriage after only a few years.

After his death, Murasaki Shikibu once again faced deep solitude.

It’s said her writing in The Murasaki Shikibu Diary changed during this time.

Though not directly stated, sorrow seems to seep between the lines.

Perhaps the more quietly she loved, the deeper her loss became.

In that era, exchanging poetry was part of courtship—a way to build intimacy.

She and Nobutaka are said to have traded verses, some of which hint at sensual encounters, like this one:

How I long for the night—

when in the mingling shadows

your presence, hidden like the moon,

touches me again.

Their bond blended intellect with emotion,

a love defined by words more than by touch—quiet, yet sure.

A Wavering Heart and the Beauty of Distance

From Wife to Woman Again

After becoming a widow, Murasaki Shikibu’s name became linked to several rumored romances—the most famous involving Fujiwara no Michinaga.

Michinaga, the de facto political ruler of the time, summoned her to court and appointed her as a tutor to his daughter Shōshi (Empress Akiko).

Records confirm they exchanged letters, and in one she writes,

“Your handwriting reads my heart.”

—A phrase that leaves much to interpretation.

Court gossip swirled about their relationship, and other court ladies viewed her with a mix of jealousy and curiosity.

Was it love? Trust? Or merely a balm for loneliness?

We can’t say for certain.

But it seems she was the only person who kept a respectful distance while also revealing her heart to Michinaga.

Genji’s Dream, the Shadow of Reality

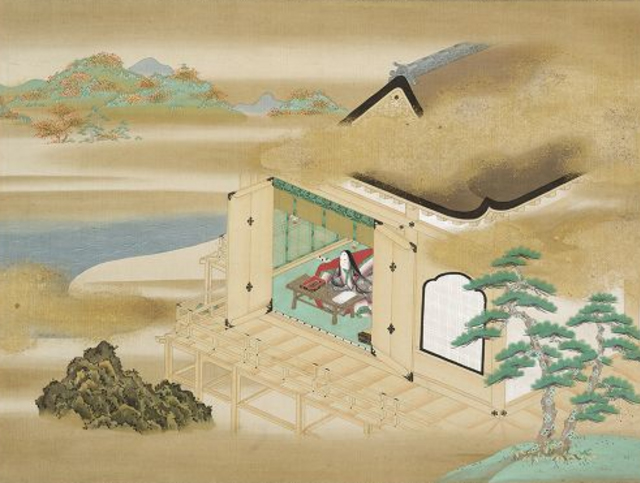

Love at the Tip of Her Brush

The protagonist of The Tale of Genji, Hikaru Genji, is a beautiful nobleman who romances many women.

Yet behind his womanizing lies a stream of unfulfilled longing and loneliness.

Murasaki Shikibu is said to be the first writer to portray such “male weakness.”

The erotic scenes in Genji are not mere fiction—they likely reflect her own experience and astute observations.

One famous scene involves Genji’s forbidden affair with his stepmother, Lady Fujitsubo.

Though taboo, the moment is rendered with breathtaking beauty and quietude, drawing readers into a space between sin and surrender.

Another memorable scene depicts Genji’s first night with Murasaki no Ue, where the transformation of a girl into a woman is portrayed with delicacy and pain.

Here, Murasaki captures innocence and vulnerability, love and anxiety, all in a single breath.

The women in her stories are cunning, tragic, and full of strength.

Though powerless against fate and tossed by love, they refuse to surrender their pride.

They are, in many ways, her own reflection.

The Difference Between Tears and Ink

Murasaki Shikibu was not someone who easily expressed emotion outwardly.

Her Diary offers a glimpse into her inner world—a court life weighed down by expectations, protocol, and quiet sighs.

Lonely even in company.

Doubtful even when praised.

Longing to be loved, but unable to fully believe it.

Perhaps her brush was her way of weeping.

Her writing contains sharp observations of others—like the moment when court poet Akazome Emon glances her way and laughs, or when she watches other ladies in love from afar.

These scenes reflect her emotional restraint—

not coldness toward love, but a quiet reverence for it.

On paper, she could be honest without reserve.

There, at least, she didn’t want to lie.

Rather than being indifferent to love, she seemed to understand the value of distance—loving without making noise.

That gaze gave her literature its dignified beauty.

A Fire Within the Stillness

She Could Only Love by Writing

Murasaki Shikibu’s view of love was never grand or showy.

It didn’t blaze—it smoldered, deep and slow, in the depths of her chest.

More than craving someone.

More than hating someone.

She simply wanted to quietly sit inside their heart.

Less like love, more like prayer.

Less passion, more devotion.

And perhaps because that was the only way she knew to love,

she could portray the hearts of so many women so truthfully.

Love transcends time.

Murasaki Shikibu’s love, too, never spoke aloud, never took form—

but through her brush, it gently seeped into the world.

To those carrying a love they can’t name.

To those with a longing that has no place to go.

She quietly offers her stories.

So the flame in your heart

won’t flicker out in silence.

No definitive record remains of her final days.

It is said she quietly laid down her brush around 1014,

but her cause of death, even her parting words, are lost.

What is certain is that her brush stopped—and the tale closed.

Perhaps she faced her paper, lit her incense,

and wrote, to the end, of a love she never revealed to anyone.

Though her name fades with time,

her story still lights a fire in your heart.

日本語

日本語