Cleopatra’s View of Love | The Egyptian Queen of Passion and Power

Born on the winds of the Nile, she captivated men and shook empires — Cleopatra VII.

Her name, even after thousands of years, still stirs the imagination as a symbol of love and power.

In this article, we focus on the history and love of Cleopatra, tracing the heart of a queen who lived between myth and reality.

Behind the labels of “seductress” and “strategist” often found in textbooks, there existed a quiet will — that of a woman who turned love into both her weapon and her shield.

What did she feel when she loved, and what resolve carried her through life?

Here, we will gently unravel the path of her love.

The Beginning of a Queen Who Loved

A Greek-Blooded Queen of Egypt

In 69 BCE, Cleopatra was born into the Ptolemaic dynasty of Greek origin.

Her name meant “glory of her father,” and she was raised as a daughter of royalty.

But her identity was complicated.

Though known as the “Queen of Egypt,” she wasn’t ethnically Egyptian—her lineage traced back to Macedonia.

To the Egyptian people, she may have seemed like a goddess from another land.

Still, she was the first of her royal family to master the Egyptian language.

She paid deep respect to the local gods and customs.

Even at a young age, Cleopatra understood this simple truth:

“To rule, one must first know how to love.”

Exile from the Throne, and Her First Taste of Despair

At seventeen, Cleopatra was crowned co-regent with her younger brother, Ptolemy XIII.

Though technically married to him, it was little more than a political formality.

The reality was a brutal struggle for power.

Intrigue, poison, betrayal—

the standard tools of ancient courts swirled around her as if by default.

Eventually, the rift between her and her brother grew irreparable.

She was forced into exile, fleeing the palace for Syria.

But Cleopatra did not collapse in grief.

Instead, she quietly began to plan.

To reclaim her throne, she would need a force greater than any within Egypt.

That force was Rome.

And at its heart was Julius Caesar.

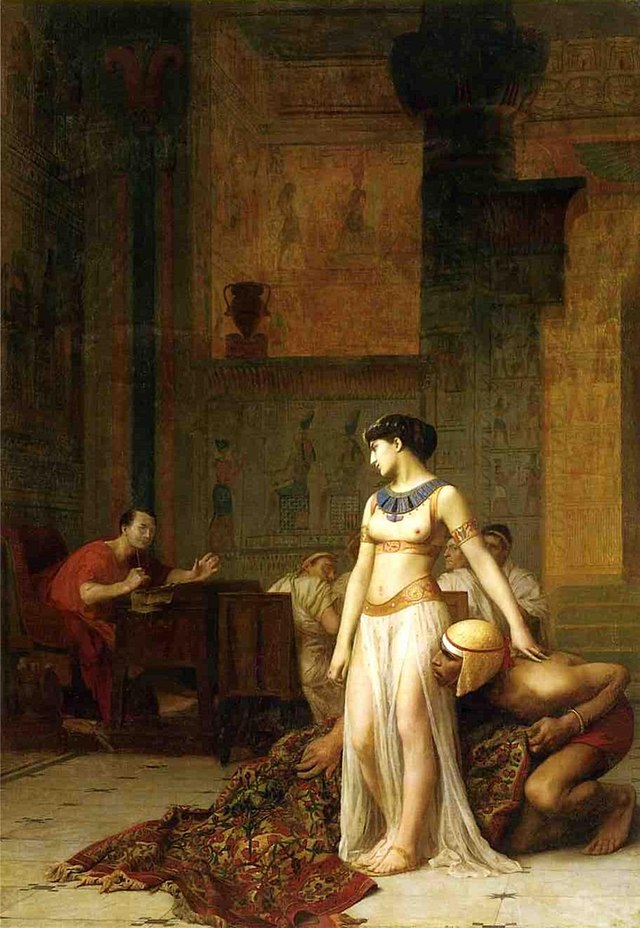

A Night with Caesar — The Legend of the Carpet and the Scent

In 48 BCE, in Alexandria, Caesar arrived to mediate the royal conflict in Egypt.

That night, Cleopatra made her move.

Wrapped in a long Persian carpet, she had her servants smuggle her into the palace.

In a stone hall flickering with candlelight, after the eunuchs had departed,

the rug was unrolled before Caesar.

And there she was—

a young queen draped in the scent of oil and wild fruit,

her eyes as deep as the night,

her fingertips not just royal, but unwavering in their intent.

Caesar did not draw his sword.

Instead, he offered his hand.

Perhaps in that moment, he understood everything:

That she was not merely beautiful,

but wise, burdened with a kingdom,

and a woman who had chosen survival over affection.

Her voice began in fluid Greek,

then shifted to flowing Latin.

Political conversation mingled with sly smiles.

The general and the queen spoke until dawn.

Love and Power — An Equal Exchange

Caesar restored her to the throne.

But this was not mere charity.

He saw Cleopatra not as a pawn, but a partner.

She, in turn, pledged her loyalty to Rome—

and gave him her heart.

Soon after, a son was born: Caesarion.

He was both the fruit of love and a “seed of history,”

blending the bloodlines of Ptolemy and Caesar.

How calm was Cleopatra at that moment?

Did she allow herself to dream, even for a second,

that she was allowed to be loved?

Perhaps.

But she was also the first to awaken.

Alone in Rome, and Unloved in Reality

Invited by Caesar, Cleopatra brought Caesarion to Rome.

But for her, it was no grand stage—only a foreign cage.

The Roman citizens did not welcome the exotic queen.

Her skin tone, her perfume, her gods, her demeanor—everything about her was alien.

Whispers followed her in the forum.

Some called her a seductress.

As Caesar openly favored her despite having a Roman wife,

the air in Rome grew cold and cruel.

She was both a queen and a mere “guest.”

Back in Egypt, she was revered as a living goddess—

but here, she was just “too much.”

At night, she dreamed of the Nile.

A place where her words meant something.

A place where she knew who she was.

But she didn’t cry.

Because to love and to be loved—

are rarely the same thing.

What She Left Behind as She Departed

In 44 BCE, Caesar was assassinated in the Senate.

As daggers plunged into his chest,

Cleopatra may have already been thinking of her next move.

Without fuss, without resistance,

she took Caesarion and quietly left Rome.

Not to escape.

But to protect her story—

as a ruler,

as a mother,

as a woman.

On her back, she carried the sorrow of a woman unloved,

and the pride of a queen who refused to stop loving.

Antony — A Man of Passion and Intoxication

After Caesar’s death, Marcus Antonius emerged as one of Rome’s new power holders.

His meeting with Cleopatra was like fire meeting perfume—

immediate, overwhelming, all-consuming.

Antony was more “human” than Caesar had been.

Strong yet fragile, emotional and starved for affection.

To him, Cleopatra gave both her kingdom and her heart.

They shared their days,

bore three children including twins,

and filled their Egyptian nights with pleasure and devotion.

But their way of life clashed violently with Roman morals.

Soon, whispers reached Rome:

“Antony is under her spell.”

And such whispers were enough to ignite war.

A Foreseen Ruin, and the Final Love

In 31 BCE, the Battle of Actium sealed their fate.

Cleopatra and Antony’s fleet, chaotic and scattered, fell to Octavian’s forces.

They fled—not with hope, but with a sliver of peace—

back to Alexandria, once their paradise.

But the paradise was gone.

The herbs in the garden had withered.

The fountains fell silent.

The paintings on the walls had faded into melancholy.

Death, as always, crept in without a sound.

Still, they shared those last days.

They wrote letters, held their children,

sipped wine, and talked until the sky turned black.

Cleopatra is said to have asked:

“Did you love me?”

And Antony may have smiled and replied,

“From the beginning, I was ready to die for it.”

As Roman troops closed in,

Antony was told—falsely—that Cleopatra was dead.

In despair, he took his own life.

She received the news not with screams,

but by sinking silently to her knees.

She was brought to him,

and kissed his forehead.

That was their final exchange.

She spent several days preparing herself.

She chose her final robes, adorned herself in gold and pearls.

This was no defeat—

it was a queen’s final, personal performance.

The story goes that she held an asp to her breast.

That even death was part of her stage.

When its fangs met her skin,

she looked, they say, like a child falling asleep—

a touch of relief,

a quiet end.

To call her “a woman who lived for love” feels inadequate.

Her death was not an escape from love—

it may have been its completion.

What Was Cleopatra’s View of Love?

Cleopatra’s view of love was not the dream of a girl who merely wished to be adored.

It was the wisdom to move a nation — and the resolve to bear solitude.

Her love for Caesar was a strategy for survival.

Her love for Antony was a salvation to reclaim her heart.

And in the end, what she chose may have been a love that no one could command.

Love, for her, was not submission — it was the courage to stake one’s very self.

Even in death, she continues to ask us what love truly means.

— Perhaps Cleopatra’s love was not a tragedy, but an eternal declaration.

日本語

日本語