Napoleon’s View of Love|Who Was the One Woman an Emperor Couldn’t Possess?

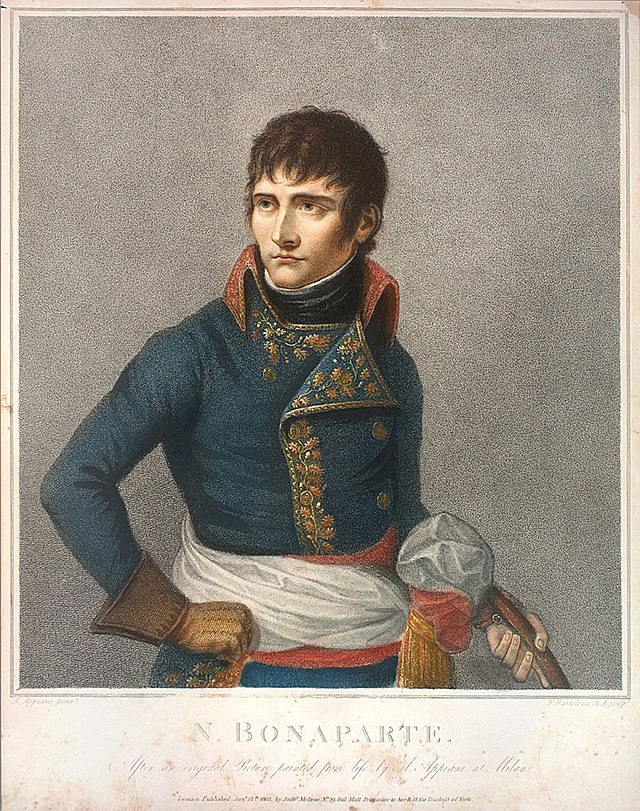

A boy born on the Mediterranean island of Corsica would one day build an empire and shake the world—

Napoleon Bonaparte.

Racing through the storms of revolution and triumphing on countless battlefields,

his life was forever shadowed by two inseparable forces: victory and loneliness.

And behind them lingered the memory of a woman—one he could never conquer by strategy or sword.

This article explores Napoleon’s view of love and life, tracing the path of his emotions hidden beneath the armor of an emperor.

The Solitude of the Boy Napoleon

Of Mothers, Islands, and the Origins of Loneliness

Napoleon’s origins lie in the winds of Corsica.

As a child, he lost his father early and was raised by his strict mother, Letizia.

She ruled the household like a soldier—disciplined, restrained, and seldom expressive of her emotions.

Young Napoleon loved books and spent long hours in quiet thought.

Yet inside him burned a small, fierce flame—a desire to be seen, to be acknowledged.

When he was sent to a military academy in mainland France,

he found himself surrounded by the sons of nobles, isolated and mocked as a “foreigner.”

He began to lose his sense of belonging.

That loneliness shaped him into a man of ambition.

But at the same time, it nurtured within him an unnamed longing—to be loved deeply and without condition.

In the years to come, this would become his eternal struggle:

to learn that to win and to be fulfilled were two entirely different things.

The Young Napoleon’s Wandering Heart

After graduating from military school and becoming an artillery officer, Napoleon slowly began to rise amid the storm of revolution.

The chaos in Paris, the siege of Toulon, the suppression of the Vendémiaire uprising—on these battlefields, his name began to take root.

In his youth, Napoleon is said to have harbored a gentle affection for a young woman named Élisabeth Le Mierru.

She was the daughter of the Valois family, with whom he stayed as a cadet—a girl of grace, intellect, and kindness.

Between his studies, the young officer would recall her smile and write letters to her each night.

“Every time I remember your voice, my heart grows warm.”

Those words were less a confession of love than a quiet prayer from a lonely boy.

But the tender bond did not last long.

The difference in their stations—and the uncertainty of a nation on the brink of revolution—quietly closed off their future.

In time, Napoleon tore up the letters and turned once more toward the world of study and ambition.

The Young General’s First Spring

Sunlight in Marseille

At twenty-five, Napoleon temporarily left the army amid the turmoil of the Revolution and stayed in Marseille.

There he became acquainted with the family of a silk merchant, the Clarys—and met a sixteen-year-old girl named Désirée Clary.

She was said to be lively, spontaneous, and bright-eyed—a girl untouched by the noise of Paris, like a ray of southern sunlight.

Napoleon was quickly drawn to her and soon became a frequent guest at the Clary home.

In her presence, he would crack jokes and blush, exchanging letters again and again.

Before her, he was neither the cool strategist nor the fiery general—just a young man awkwardly learning how to love.

But fate had already begun to turn elsewhere.

Recalled to Paris, Napoleon was consumed by military and political duties, and the warmth between them slowly faded.

The letters stopped, and even their words grew cold.

It is said they were once engaged, but the promise quietly dissolved.

Years later, on the lonely island of Saint Helena, Napoleon reflected:

“Had I married her, perhaps my life would have been a peaceful one.”

—In that brief sunlight of Marseille, he lived not for ambition, but, for once, simply for love.

The Spell Called Joséphine

The Scent of Love—and the First Unease

At twenty-seven, as he began to make a name for himself as a general in the turbulent streets of Paris, Napoleon met the woman who would change his life forever.

Her name was — Joséphine de Beauharnais.

She was a widow six years his senior, with two children, known in Parisian society for her grace and the subtle fragrance that seemed to linger around her.

To the young general, who had lived in a world filled with the sound of marching boots, she appeared almost like a creature from another world.

Napoleon fell in love instantly.

Or rather, it was less a love than a feverish kind of devotion.

His letters to her burned with passion, as if written by a poet overcome with intoxication.

It is said that Napoleon even grew jealous of Joséphine’s little dog, Fortuné.

The great conqueror of continents was genuinely irritated by the small creature that occupied her lap, sighing each night in helpless frustration.

The heart of a conqueror, it seems, could be surprisingly delicate.

“Three days without your letter—I am going mad.”

“I long for your scent.”

“Come to me as you are, with nothing between us.”

Even heroes are defenseless when they fall in love.

And in that defenselessness, Napoleon’s humanity shone brightest.

A Love Out of Sync

But Joséphine occupied a different emotional space.

Napoleon was young and desirable, yes—but his intensity could be overwhelming, even suffocating.

She could not return his fervor.

And the imbalance began to erode their bond.

While he was away at war, Joséphine found comfort in other men.

When he discovered this, he reportedly shattered dishes, slammed his desk, and fell into a fury.

But more than anger, it was sorrow—quiet and aching.

“I’ve heard rumors of your affair. I feel like I’ve been thrown into a stormy sea, alone.”

“Your silence wounds me more than cannon fire.”

It wasn’t rage—it was a man lost in the face of betrayal, unable to confront love’s collapse.

Yet still, he made her his empress.

Perhaps it was a kind of proud defeat—choosing to embrace even her flaws.

Between Love and the Imperial Throne

A Coronation Named Goodbye

In 1804, Napoleon was crowned Emperor of France.

Yet beneath the weight of that crown, an unfulfilled ache lingered in his heart.

The absence of a child with Joséphine—

that, more than any war or crown, was the wound that tormented the emperor most.

He changed doctors, prayed through countless treatments, but nothing changed.

In time, he came to believe the cause lay with her.

And soon, other women began to drift through the chapters of his life.

There was Éléonore Denuelle, a gentle lady-in-waiting who cared for him while Joséphine was away.

Haunted by the fear that he might never father a child, Napoleon sought the answer through her.

Éléonore bore him a son—Charles Léon—and with that birth, Napoleon gained the certainty that his bloodline could indeed continue.

Then, in Poland, appeared Countess Marie Walewska.

She had approached him out of duty to her homeland, yet became the woman who soothed his solitude.

Their bond, tender and quiet, blurred the line between politics and love—and brought forth a son, Alexandre.

There was also Marguerite Georges, the celebrated actress of the Paris stage.

Their brief affair became the talk of society, a reminder that even emperors are, after all, merely men.

Through it all, Joséphine did not reproach him.

Instead, she brought calm to his court, wrapping his loneliness in her quiet grace.

But the empire demanded an heir.

In the face of politics and history, love was no longer enough.

Their separation was inevitable—

a quiet farewell, almost theatrical, as if rehearsed.

They spoke their lines with trembling lips, and the curtain fell.

“Your tears weigh more than all my honors.”

Those words remained—

the final truth of a man who had conquered the world, yet never ceased to long for love.

A Marriage of Diplomacy

Just three months after divorcing Joséphine, Napoleon remarried.

His new bride: Marie Louise, 19-year-old daughter of Emperor Francis I of Austria.

It was a marriage of pure diplomacy.

By marrying into the old European royalty, Napoleon sought to lend legitimacy to his empire.

Despite the 18-year age gap, Napoleon offered her gentle affection, and she gradually warmed to him.

In 1811, their long-awaited son was born—Napoleon II, styled King of Rome.

In this child, Napoleon placed all his imperial dreams.

But this love felt different from his past.

It was more practical than fated—more function than feeling.

Though Marie Louise grew fond of him, after his fall from power, she returned to Austria, remarried twice, and lived apart from their son.

That quiet separation may have been another small heartbreak in Napoleon’s disillusionment with love.

He fathered several illegitimate children as well, including Charles Léon by Éléonore Denuelle, whom he reportedly supported financially.

Still, the time he spent with Joséphine may have been the only “family” he truly loved.

The Shape of an Unchanging Heart

He Never Stopped Loving Her

Even after their separation, Napoleon never forgot Joséphine.

He sent her gifts, paid for the upkeep of her home at Malmaison, and dispatched envoys whenever he heard she was ill.

In the clothes and perfumes he chose for her, there was not a trace of “a love once lost,” but rather “a love that still endured.”

Joséphine, too, after the divorce, cared tenderly for Napoleon II, abandoning all ambition and living out her days in quiet grace.

In 1814, she fell ill with pneumonia and passed away at the age of fifty.

When Napoleon received the news, he was deeply shaken.

“It was she,” he is said to have murmured, “whom I loved most in all my life.”

In the Winds of Saint Helena

Defeated at Waterloo, Napoleon—then forty-six—lost everything and was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic.

It was neither a battlefield nor a palace,

but a lonely kingdom ruled only by salt, wind, and silence.

He spent five and a half years there.

Ravaged by illness, the once-mighty general who had shaken the world slowly faded into frailty.

Yet in the records of his final years, one name appears again and again—Joséphine.

In his sleep-talking, in his recollections, even in his will—her shadow quietly lingers between the lines.

“The world misunderstood me, but she understood.”

In that single phrase, it is said, dwelled the last confession of a man who had fought all his life.

On May 5, 1821, Napoleon drew his final breath.

And in that final moment, the name whispered on his lips was—Joséphine.

What Was Napoleon’s View of Love?

For Napoleon, love was not reason—it was fire.

Even as he built an empire, he remained, before one woman, nothing more than a man.

His feelings for Joséphine were neither political nor dutiful;

they were the truest emotion of his life—something for which he staked everything he had.

Because that love could never be fully possessed, it became eternal,

engraved deeper in human memory than any record of his victories.

In the end, what he gazed upon was neither glory nor defeat,

but the shadow of the one woman who had truly understood him.

—And you? How far would you let yourself burn for love?

日本語

日本語