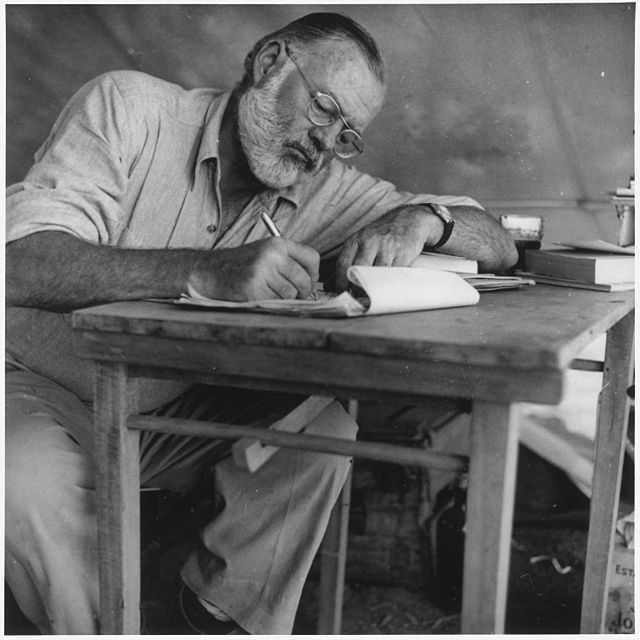

Hemingway’s View of Love|What Kind of Love Did the Writer of War Seek?

His life read like a hardbound novel steeped in the scent of whiskey and tobacco.

Ernest Hemingway —

a man who faced the tempests of war and history with a rifle in one hand and a typewriter in the other,

and carved a new language and soul into the literature of the twentieth century.

The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls —

in every story runs the pulse of death and love, solitude and pride,

and the quiet grace of those who endure.

Yet the fiercest and most perilous battles he fought were not on battlefields or seas,

but in the storm of passions kindled between himself and the women he loved.

Four marriages. Countless affairs.

Each left a mark — shaping not only his art, but the very way he lived.

In this article, we turn the light toward Hemingway’s view of love,

tracing the inner voyage of a man who lived between love and loneliness.

A Feverish Youth

A Tender Passion Blooming in the Woods

In 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois — a quiet suburb of the American Midwest —

Ernest Hemingway was born to a physician father and a music-teacher mother.

Raised in a strict yet cultured household, he grew up surrounded by both nature and art.

His father often took him into the forests and lakes of Michigan,

where he learned to fish and hunt, and to listen to the silence of the wild —

a silence that slowly sharpened his sensitivity and imagination.

His first brush with love came one summer when he was twelve,

an age when a fishing rod meant more to him than any rifle.

It happened on the shores of a lake in Michigan.

During a Boy Scout outing, he met an older girl named Sylvia.

Her braids, her smile, and the soft, poem-like voice she used beneath the trees

captivated the young Hemingway completely.

He set down his fishing rod, leaned against a tree, and looked up at the stars beside her.

The night air was sweet; her laughter mingled with the rustling of the leaves and vanished.

He was too young to know a kiss,

yet the flutter and ache of that moment would echo through his fiction again and again.

When summer ended, Sylvia returned to the city.

Nothing happened between them — and yet that very nothingness

became one of his most powerful memories.

It was the clear, fragile pain of a first love that never came true.

Another First Love: Nature Itself

There was another love that Hemingway cherished in his youth—nature.

Taught by his father, he learned the rhythm of hunting and fishing, and these were more than hobbies; they were quiet expressions of emotion.

The breath of animals, the ripples across the lake, the hush of the forest—

in these, he may have seen a form of love more certain than words.

This secret communion with the natural world would later form the undercurrent of his writing:

a silent passion, the fragile beauty of life, and the elegance of solitude.

In those woods and waters, he found his first lesson in how love could be both cruel and beautiful.

A Love That Bloomed in Wartime

Romance in Uniform and White Linen

World War I.

At nineteen, Hemingway volunteered as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross and was sent to the Italian front.

Wounded in both legs by enemy fire, he was taken to a hospital in Milan—

and there, waiting in her white uniform, was Agnes von Kurowsky, a nurse seven years his senior.

At twenty-six, Agnes radiated a classic beauty, blending grace and quiet strength.

As he lay in his hospital bed, Hemingway saw not just a nurse, but an angel behind the gauze.

With every dressing of his wounds, she gently unwrapped the defenses of his heart.

They whispered poems to each other, dreamed aloud about the future.

In the dim glow of the hospital room, it wasn’t the sound of shells that filled the air—it was the rhythm of two hearts.

Hemingway spoke seriously of marriage.

In his letters, he wrote:

“A world without you is painted in grey.”

To which she replied:

“With you, everything falls quiet.”

But the same war that had brought them together soon tore them apart.

As peace neared, Agnes sent a letter ending their relationship—

she had become engaged to an older army doctor.

That letter struck deeper than shrapnel.

He would later transform the pain into one of his finest novels, A Farewell to Arms, with Agnes living on forever in the form of its heroine, Catherine.

Marriage, Betrayal, and the Typewriter

A Pure Love with Hadley—and Its End

After returning home, Hemingway found himself amid the jazz and smoke of Paris’s Lost Generation.

There, he met his first wife, Hadley Richardson.

He was 22. She was 29.

Older, quiet, and modest, Hadley possessed a quiet strength that drew him in.

Within a few short months, they married.

Their life in Paris was far from glamorous.

They had little furniture, often no heat, and shared wine in their coats, huddled together for warmth while Hemingway typed at a small desk.

Hadley supported his writing wholeheartedly.

She typed his manuscripts, stood by him during creative droughts, and never asked for more than his presence.

Then, one day, tragedy struck.

On a train, Hadley lost a suitcase that contained all of Hemingway’s early manuscripts.

She wept in apology. Hemingway raged—

but then held her, forgave her.

Or perhaps, he could forgive only because he loved her.

He would later reflect:

“Had I blamed her then, my whole life might have come undone.”

With the birth of their son, Bumby, came warmth and domestic calm.

But as Hemingway’s fame grew, so did his restlessness.

And the name of that restlessness?

Pauline Pfeiffer—Hadley’s “friend.”

A Chain of Love and Collapse

From One Wife to Another—A Pattern of Shifting Hearts

Hemingway’s relationship with Pauline Pfeiffer began while his heart still smoldered with the ashes of Hadley.

Pauline was a journalist for Vogue—intelligent, elegant, and composed.

Where Hadley had been reserved and gentle, Pauline was driven, sharp-witted, and confident.

Hemingway was soon captivated by the electricity between them.

After marrying Pauline, their lives changed dramatically.

Her wealthy uncle provided them with luxury: a grand house in Key West, Florida, and a private studio just for Hemingway’s writing.

Yet the comfort dulled his creative edge.

They had two sons, but Hemingway never fully settled into fatherhood or domestic life.

His attention drifted, his restlessness returned.

A Woman of Passion Found on the Battlefield

Then, on assignment during the Spanish Civil War, Hemingway met a new storm of a woman—

Martha Gellhorn, a war correspondent as fearless with her pen as she was with grenades exploding nearby.

He was instantly drawn to her fire and strength.

Pauline—once a source of vitality—was now a shadow behind him.

He ended their marriage with barely a backward glance, and Martha became his third wife.

But even she, strong and independent, proved too much.

Hemingway grew resentful of her autonomy.

What had once drawn him in now made him feel inferior.

Their marriage, built on war and passion, collapsed in just five years.

He might have loved her—but he never learned how to stay in love.

Final Love and the Quiet Before the End

Mary Welsh, the Last Wife, the Last Refuge

Mary Welsh. Hemingway’s fourth wife. The woman who stayed until the end.

They met during World War II, both working as correspondents. She was sharp, witty, courageous—a journalist in London with a spine of steel and a flair for bourbon.

Through shared stories from the front and the clatter of typewriters under bombardment, the two drew closer, bonded not by romance alone but by survival.

They married in 1946.

“With her,” Hemingway once said, “I need nothing else.”

Mary became his final sanctuary—a place of quiet understanding, of refuge from both the world and himself.

Their life in Finca Vigía, a hillside estate in Cuba, was Hemingway’s brief glimpse of peace.

He wrote in the mornings to the rhythm of Caribbean winds, fished in the afternoons, and sipped mojitos by sunset.

Evenings were spent with Mary, not in fire and passion, but in stillness—what passed for intimacy in the life of a man who rarely let down his guard.

But even in that calm, darkness seeped in.

Injuries from car crashes.

Lingering trauma from wars.

Alcohol. Depression. The slow erosion of the mind.

By the late 1950s, he was plagued by paranoia, hallucinations, and crushing melancholy.

Electroshock therapy blurred his brilliance. The typewriter grew silent.

Mary watched him fade, piece by piece.

And on a July morning in 1961, Hemingway picked up his favorite shotgun and ended the story himself.

Mary kept her silence for years.

When she finally spoke, she said,

“I do not mourn what I couldn’t save.I am proud of having been loved by him.”

That quiet declaration was her final letter to the world, written not with ink, but with memory.

What Love Leaves Behind

The Soul’s Shadows and Letters Never Mailed

Hemingway’s love life followed a certain pattern.

Even as he held one love in his arms, his heart would lean toward the next.

He was a man always half-in, half-leaving, carried forward by the scent of fresh desire.

Each new passion was both escape and combustion.

In his later years, readers didn’t just ask him about writing—they wrote to him about love.

Soldiers’ widows, struggling housewives, teenagers reeling from their first heartbreak.

And Hemingway, surprisingly, answered many of them.

Not with condescension.

Not as a master of love, but as a fellow survivor of it.

To a woman grieving a lost fiancé, he wrote:

“If love doesn’t hurt, it hasn’t started yet—or it’s already over.”

To another:

“Love is more complicated than war.In war, at least you know who the enemy is.”

These were not just answers.

They were fragments of a broken mirror, each reflecting his own wounds.

Through them, he examined his failures—not as regrets, but as truths worth writing down.

Love Was the Harder War

Hemingway’s view on love was always a paradox.

He tried to dominate love like a battlefield, but he longed to surrender to women who needed no saving.

He was drawn to strength, only to be frightened by it.

He craved tenderness, only to sabotage it.

Love, for Hemingway, was a war he kept re-entering, never quite knowing why.

And in the end, what he found wasn’t a medal, or applause.

It was silence—and within that silence, loneliness.

That morning, with the shotgun in hand, perhaps the last thing that remained in his heart was not fear,

but something more haunting:

The unbearable sense that he had not yet loved enough.

Let us end as he might have:

by leaving behind a question instead of an answer—

Was love, for Hemingway, a bell that never stopped ringing?

And if so, then perhaps his entire life was an attempt to answer the question:

For Whom the Bell Tolls?

And maybe—just maybe—it tolled for love.

日本語

日本語