Einstein’s View of Love|What Equation of the Heart Could the Genius Not Solve?

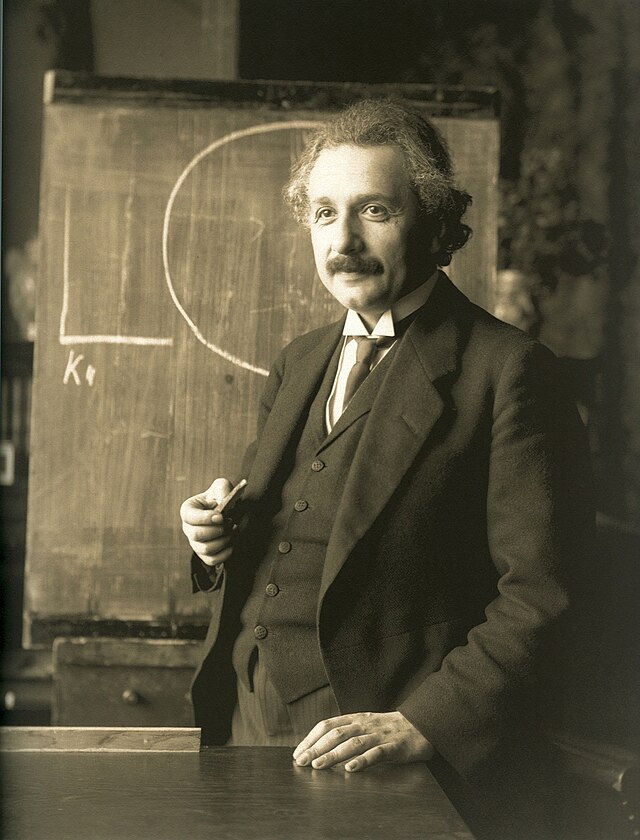

Albert Einstein.

The man who formulated the theory of relativity and is hailed as the greatest genius of the 20th century.

But inside that brilliant mind swirled not only equations—

it also held a passionate and tangled view of love.

Born in Ulm, southern Germany, Einstein revolutionized theoretical physics while working at the Swiss Patent Office.

Behind the discoveries that changed the world lay a series of loves—at times intense, at times filled with anguish.

He wasn’t just a genius.

Even in love, Einstein was… relative.

A Childhood of Dreams and Solitude

Music, Magnetism, and First Love

Young Albert was a quiet, sensitive child.

He spoke late and often preferred solitude.

But his mind always turned inward—toward the depths of the universe and the human heart.

At age five, his father gave him a compass, and Einstein became obsessed with the “invisible forces” it revealed.

There was a piano at home.

He would close his eyes, listening to his mother play Schubert.

And even he had a faint memory of first love.

Her name was Lise, an older girl who lived next door.

She had dark hair and sang like a bird.

Einstein admired her—but was said to have grown frustrated that he couldn’t express his feelings through formulas.

Later in life, he would say:

“Music is a substitute for love.”

Surely, the memory of Lise lingered in that thought.

Heat and Hesitation in Youth

Love Letters and Escapism as a Student

During his time at ETH Zurich, Einstein was unexpectedly prolific with love letters.

He preferred lively debates in cafés over lectures.

On his desk sat equations—and sometimes flirtatious letters side by side.

He often wrote impassioned messages to classmates and women he met in town.

“Your smile reached my heart faster than the speed of light.”

Even his pick-up lines hinted at relativity.

At the same time, he struggled to find work after graduation and faced mounting psychological pressure.

Love, perhaps, was his way of escaping reality and affirming his self-worth.

Between Love and Equations

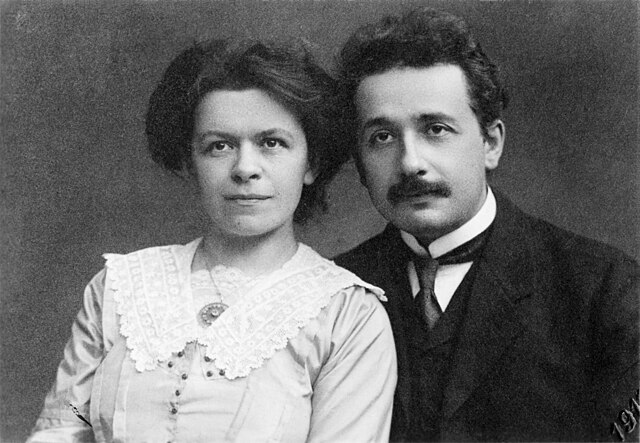

Meeting Mileva Marić

In 1900, at age 21, Einstein met Mileva Marić, a fellow student at ETH Zurich.

She was a rare woman studying physics at the time—a brilliant, Serbian-born intellectual.

Einstein was immediately drawn to her.

“Whenever I talk with you,” he wrote, “the world looks different.”

Between them flowed a tension—part friendship, part romance—charged with intellectual chemistry.

They married in 1903.

Shortly before that, the couple had a daughter, Lieserl, whose fate remains a mystery.

Some say she was given up for adoption; others, that she died young.

The truth is still hidden in the mist.

Marriage and Its Collapse

Though Einstein now had a family, his passion for research and the pressures of daily life slowly eroded their bond.

In 1905, at age 26, Einstein published a series of papers now known as his “miracle year,” including the special theory of relativity.

At the time, he was an unknown patent clerk.

But those papers sent shockwaves through the world of physics.

He soared to fame—

While Mileva, buried in domestic life, faded into the background.

Eventually, Einstein presented her with a list of 13 conditions for cohabitation:

“You must not speak to me.”

“You will obey my orders.”

“You must not enter my study or bedroom uninvited.”

It was less a marriage contract than a treaty of efficiency.

They divorced in 1919 when Einstein was 40.

As part of the settlement, he promised her the prize money if he ever won a Nobel.

In 1921, at age 42, he did just that.

A Second Marriage, But Peace Remained Elusive

The Cousin: Elsa

In the same year as his divorce, Einstein married his cousin Elsa.

She was devoted and domestic.

“She even worries about the wrinkles in my trousers,” he once said.

But even this relationship began to fray.

Despite the marriage, Einstein continued to engage with multiple women—

assistants, journalists, the wives of doctors, even the daughters of friends.

His letters scattered remarks to various women—like a romantic logbook:

“Today I walked by the lake with Berta. I missed you, of course. Though I must say, her hat has worse taste than yours.”

Behind the witty charm lurked a lack of accountability in love.

Women drawn to Einstein were enchanted not just by his intellect and humor,

but by his rebellious, nonconformist spirit.

One woman even said:

“Looking into his eyes made me feel I finally understood why the Earth turns.”

But often, his love was one-sided.

Women who came seeking intellectual companionship often found themselves absorbed into his orbit—

losing their own gravity in the process.

Setting Conditions for Love

Einstein seemed to seek “laws” even in love.

In one letter, he listed requirements for any potential partner:

“Don’t interfere in household matters.”

“Don’t intrude on my time.”

“Limit jealousy.”

It was love as experiment—conditions carefully set.

Some of his lovers couldn’t even reveal their relationship.

They were married, students, or colleagues—identified only by initials or symbols in his letters.

He once joked to a friend:

“If I were ever sued for my love life, half the jury would be my ex-lovers—and the other half, their husbands.”

His many overlapping affairs, including sexual ones, did not seem to weigh on him.

To Einstein, perhaps, they were extensions of curiosity—another experiment to understand the human condition.

Late Letters and Quiet Philosophy

The Secretary: Helen

In 1933, Einstein fled to the U.S. to escape the rise of the Nazis.

For the next two decades, his companion was Helen Dukas, his secretary.

She wasn’t an academic collaborator—she was his emotional anchor.

It’s unclear if theirs was a romantic relationship,

but after Elsa’s death, Helen continued to quietly support his daily life.

She helped draft letters, soothed his moods—

like a gentle assistant helping a weary old astronomer close his celestial journal.

Between Love and Freedom

Einstein’s late letters brim with insight on life and love.

He spoke often of the “freedom to escape the bonds of human entanglement,”

and of the truths seen only in solitude.

And yet, even then, his letters to women carried a youthful thrill.

“Every time I recall your voice, the universe seems to open up in silence.”

To him, love was not a feeling to be solved—

It was elusive, ambiguous, and sometimes broken.

It was in that uncertainty where he may have found true beauty.

At the Edge of Relativity

Einstein’s romantic life was, in a word, “free”—and equally “lonely.”

He loved.

He was drawn to many women, let them go, betrayed some, admired others.

But beneath it all churned two opposing desires:

To be understood—and to never be bound.

The love that poured from his brilliant mind took no single form.

It was a constellation of feelings—always shifting, always relative.

No matter how much he unraveled the universe,

the human heart remained an equation with no solution.

日本語

日本語