Benjamin Franklin’s View of Love|What Kind of Love Struck the Inventor of Lightning?

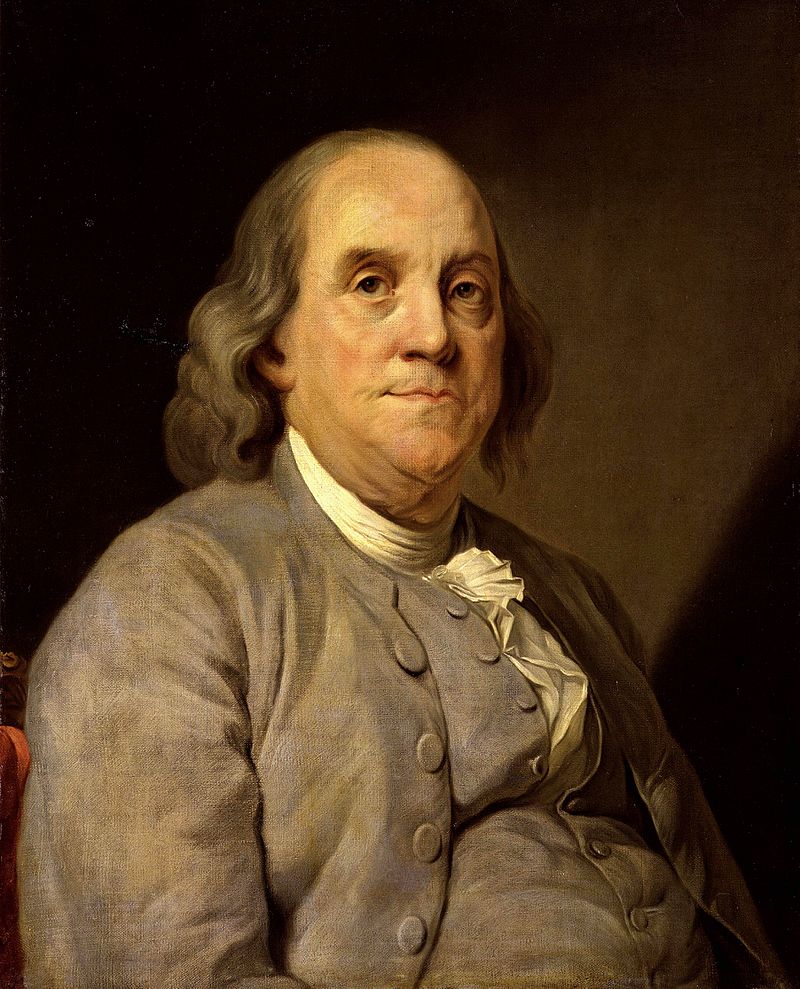

Benjamin Franklin.

Born in 1706 in Boston, the fifteenth of seventeen children in the household of a humble candle maker,

he grew up surrounded by noise, warmth, and light.

As a statesman, he helped draft the Declaration of Independence.

As a scientist, he unveiled the mystery of lightning.

He was also a diplomat, an inventor, a writer — a true giant of intellect and action.

Yet behind that brilliance flickered a passion as unpredictable as the lightning he once captured.

In this article, we turn our gaze toward Benjamin Franklin’s history of love—

tracing the emotional journey of a man who lived between reason and desire, intellect and fire.

Before Youth: The First Glimmer of Love

The First “Something-Like” Feeling

When Benjamin Franklin was not yet ten years old, he is said to have harbored a quiet admiration for an older girl he met at church.

Perhaps the scene of her smiling sweetly as he handed back a prayer book she had dropped on the way home from Sunday service is a romantic embellishment added by later storytellers.

But considering the lifelong intellectual curiosity and observational attentiveness Franklin showed toward women, it would not be surprising if his “first gaze” began around this time.

Budding Feelings Behind the Printing Press

In his teens, Franklin worked at his brother’s print shop, where he immersed himself in words and ideas. Amid the mingled scents of lead and ink, he occasionally cast thoughtful glances at the older women who passed through.

But this was no mere schoolboy infatuation.

He observed their expressions, their words, even the rustle of their garments—as though studying the approach of a thunderstorm. His mind sought to know love, just as he later sought to understand electricity.

After running away to Philadelphia as a youth, he encountered fleeting romances—but none that rooted deeply in his heart.

Loneliness and Desire in London

At 17, Franklin crossed the Atlantic to London with an emerging sense of himself as a writer. Supporting himself in the printing trade, he penned essays and letters and engaged in brief conversations—and liaisons—with women.

But London’s winters were harsh, and the cold blankets of cheap inns offered little comfort for the spirit.

Franklin sought warmth and solace in nighttime encounters, but they often left a quiet ache behind.

One rumor tells of a brief, intense affair with “Miss T”—Miss Williams—a young woman who lived in the same boarding house. Franklin grew attached to her, blending affection and desire in a way that lingered.

Later in his autobiography, he would refer to this as “a youthful indiscretion,” tinged with nostalgia.

It may have been during this time that a distance formed in his mind between “ideal love” and “physical encounters”—a divide he would navigate for the rest of his life.

Drifting Toward Marriage

A Contract Without Paper

In 1723, the 17-year-old Franklin met a young woman shortly after settling in Philadelphia.

Her name was Deborah Read, two years his junior. Franklin fell in love and proposed, but her mother, uncertain of the young printer’s prospects, withheld her consent.

Franklin left for London. During his absence, Deborah married another man—John Rogers—who soon disappeared and was later suspected of bigamy.

Under the laws of the time, she could not legally remarry as long as her husband’s fate remained unknown. Thus, she found herself in social and legal limbo.

Nonetheless, when Franklin returned from London, he and Deborah entered into a common-law marriage—a partnership without legal ceremony.

Before this union, Franklin had already fathered a son, William, born around 1730. The mother’s identity remains unknown. William came to live with Benjamin.

Together, Benjamin and Deborah had two more children: Francis and Sarah. The family raised all three children under one roof.

Franklin noted the births in his journal with little fanfare. But the records reflect quiet reverence, responsibility, and a steady warmth that defined their household.

Love in Later Years, and a Quiet Farewell

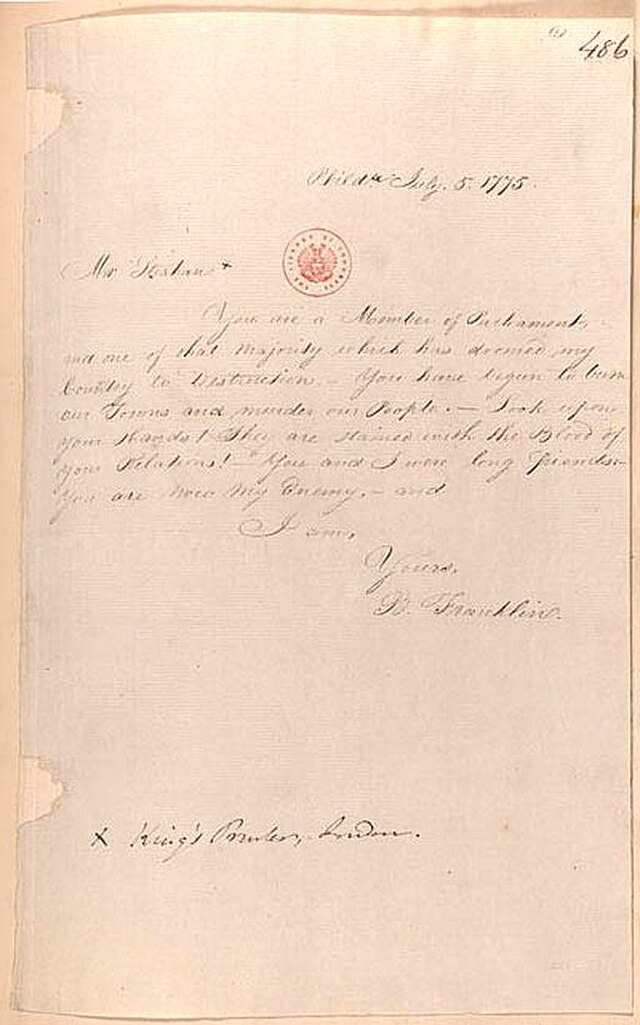

Love Letters in the City of Light

By his late 50s, a quiet, invisible distance had begun to grow between Benjamin and Deborah.

Deborah, often ill, stayed in Philadelphia. The couple’s correspondence grew sparse. Love, like a letter lost in the post, slipped out of reach.

Still, Franklin was never one to stop loving.

In his seventies, sent to Paris on diplomatic mission during the American Revolution, he carried both the weight of his nation and the lightness of an open heart.

And Paris, for all its politics, offered no shortage of warmth.

Of the many women around him, one left a lasting impression: Madame Brillon, a music-loving intellectual.

They exchanged letters often. Franklin called himself “your knight,” and she, in turn, dubbed their relationship “a small adventure.”

Their flirtation was a dance of words—passionate, but never scorching. A love letter disguised as a game.

A Proposal to a Widow, and the Philosophy of Age

Time passed, and Franklin grew fond of another: Madame Helvétius, the widow of a famed philosopher.

Unlike the light-hearted Brillon, Madame Helvétius hosted salons full of art and debate. Franklin was a frequent guest—and an earnest suitor.

He proposed marriage, but she declined, citing fidelity to her late husband.

Still, Franklin persisted, writing letter after letter with youthful zeal.

Their connection transcended the physical. It was a love formed in the spaces between ideas and glances—a dialogue between kindred spirits.

He respected her intellect and addressed her with both sentiment and reason. It was a love that defied age, position, and convention.

Why He Loved Older Women

Franklin often expressed a distinct fondness for older women.

In one of his more humorous anonymous essays, “Advice to a Young Man on the Choice of a Mistress,” he outlined eight reasons to prefer older women.

They are rational, emotionally composed, better conversationalists, trustworthy—and above all, they provide “more satisfying companionship for the mind.”

Though veiled in satire, the essay reveals Franklin’s genuine romantic philosophy.

Rather than the flash of youth, he sought thoughtful dialogue.

Instead of fervent passion, he desired wisdom and grace.

For Franklin, love was measured in depth—not intensity.

Facing Death

Letters That Last

In his later years, Benjamin Franklin lived quietly in his Philadelphia home.

His wife, Deborah, passed away at the age of sixty-six, but the two had remained in a common-law marriage for over forty years.

After her death, he spent his days surrounded by his study and his letters, embracing a life of calm solitude.

By the window of his study, stacks of old correspondence had gathered—letters written to loved ones: family, friends, and several women who had once touched his heart.

It is said that, before his deathbed, he left a few final letters addressed to his children, though much of their content has been lost to time.

Perhaps, in one of them, he left behind a line meant to make someone smile—a quiet thought, gently folded between the pages, written by a man who never stopped caring for others.

The Electric Currents of Love

Franklin’s view on love evolved continuously.

In youth: curiosity and passion.

In midlife: responsibility and choice.

In old age: respect, dialogue, and longing.

Love, he proved, is not reserved for the young.

It cannot be defined like a formula, nor predicted like a storm.

But he knew one truth: love, like electricity, is felt—not seen.

Through love, he encountered women, parted from them, and left behind not just memories—but letters.

Each one a charge of emotion, a message that still hums with life.

And perhaps somewhere within you, too, glows a flicker of light—

a small, warm voltage left by someone’s love.

日本語

日本語