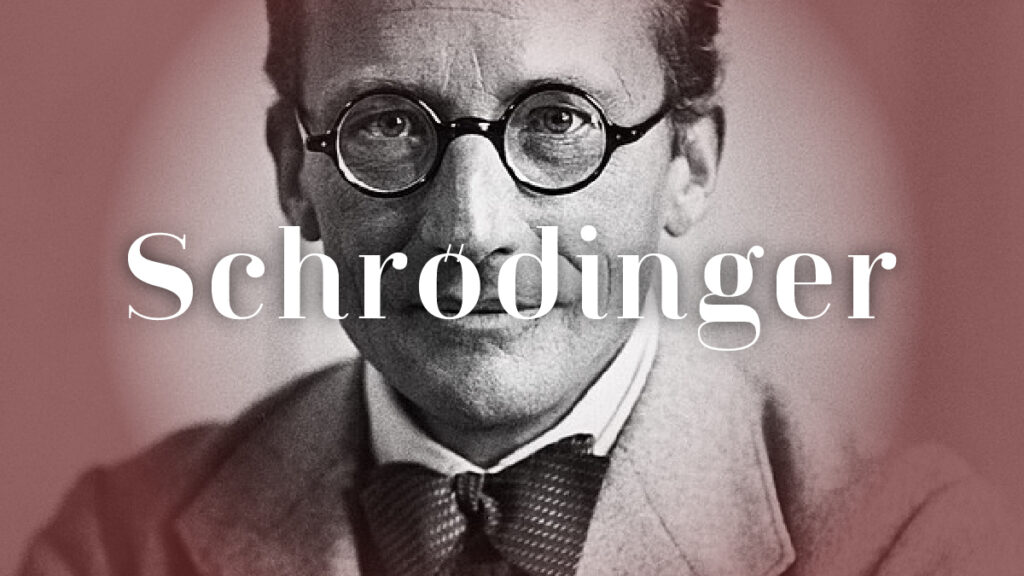

Pablo Picasso’s View of Love|The Artist Who Fueled His Life with Passion

In the history of painting, few figures lived a life that was itself a work of art as completely as Pablo Picasso.

By establishing Cubism, he overturned at the root the very notions of “what painting is” and “how reality is to be seen,” a revolutionary who kept venturing into new forms of expression—ceramics, sculpture, and more—well into his late years.

What lay beneath such creation was neither fame nor theory but love.

He fell in love again and again, seethed with jealousy, and kept painting love and sensuality even in old age. For him, love was a revelation, a curse, and above all, proof of life.

In this article, we follow Picasso’s path from childhood to his final years, focusing on the view of love that smoldered between creation and destruction.

If you can sense, even a little, the true figure of Picasso—not the one in history textbooks but the man himself—I would be glad.

When the Sound of the Brush Was Still a Lullaby

A boy in love with a pencil

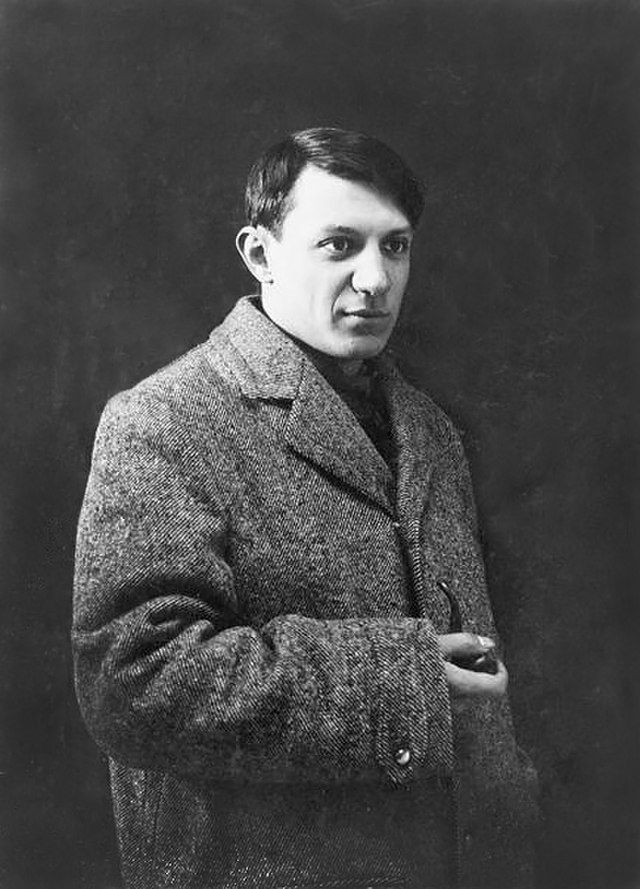

Born in Málaga, Spain, in 1881, Picasso grew up early with drawing under the guidance of his father José, an art teacher.

Their home studio was filled with models and the smell of paints, and the boy breathed that air as he grew. He naturally learned to perceive the curves, shadows, and warmth of human bodies not as “forms” but as feelings.

He loved drawing more than anything and did not take to school; in the mornings, it is said the maid had to take him there while he cried.

But once he held a pencil, the world fell quietly into place, and he knew lines expressed him better than words. According to his mother’s recollection, his first uttered word was “piz,” the latter half of the Spanish lápiz—“pencil.”

From birth, the brush was his language.

By thirteen, he already displayed skill that amazed his father; drawing was no longer play but a way of living.

The origin of his later merging of love and flesh onto a single canvas was already present in these days of boyhood.

In poverty and observation

In his teens, Picasso moved with his family to Barcelona and showed his talent at the Royal Academy. At the same time he confronted urban poverty and the illness of friends, recording the loneliness that lurks in society’s shadows.

These experiences formed the introspective motifs that would lead to his Blue Period.

For a boy who knew no romance, it might have been a time to learn the absence of love. During this period, his only lover was painting itself—silent and capricious, yet always responsive when he raised his brush. In that quiet dialogue with the canvas, he had already begun to know the essence of loving.

When Loneliness and Love Changed Color

In blue Paris, embracing solitude and poverty

Before turning twenty, Picasso first set foot in Paris—a city wrapped in mist and the smell of cigarettes. Life at the foot of Montmartre was poor, yet for him it was an exhilarating time: he painted by day and shared wine with poets and penniless artists by night.

But the deaths of friends, the absence of love, a bottomless solitude—these feelings filled his paintings with a quiet blue. Thus began what would later be called the Blue Period.

Blue was his symbol of sorrow, and also a calm color that enveloped human beings with love.

Gradually, a pale hope, like light filtering up from the depths of poverty, began to cast pink and gold into his pictures.

As he painted harlequins, dancers, and circus families, his world slowly turned rose, with warmth akin to love taking up residence in his art.

Desire and Jealousy Under the Same Roof

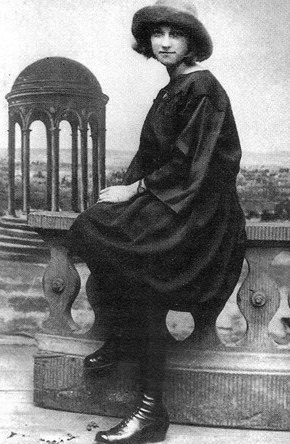

At twenty-three, Picasso met Fernande Olivier (then twenty-two), a beautiful, free-spirited, strong-willed model.

They quickly fell in love and began living together in Montmartre’s Bateau-Lavoir. The room mingled the smell of paint with her laughter—days where love and art swirled together.

Picasso drew her body again and again—lines like caresses, shadows tinged with jealousy.

Fernande soothed him, and at the same time tested and hurt him. Love was fuel for creation and also the fire that scorched him.

Around this time he is said to have conceived Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. The women’s masked, distorted faces may reflect the fear within his relationship with Fernande—a foreboding of control and destruction behind love.

Weary of passion and jealousy, his heart would gradually begin to seek quiet.

A Quiet Love and an Eternal Farewell

Past thirty, Picasso met Marcelle Humbert—stage name Eva Gouel—a gentle, reserved woman.

Some say they met through Fernande’s acquaintances, others that it was at a gathering of painters. In any case, to Picasso she was like a drop of rain after the storm.

She was kind and modest, the opposite of Fernande. He called her “truth,” and grew so devoted that he hid phrases such as “Ma jolie” and “Eva” in his works.

But the calm happiness did not last. Eva fell ill and, while Picasso nursed her, died.

He would go on calling her name in his paintings. Some say that loss guided him toward the new language of Cubism.

To grasp love in three dimensions—perhaps it was an attempt to retrieve, in another plane, her form he could no longer touch.

His love always traveled between creation and destruction. Holding both Fernande’s passion and Eva’s stillness, his heart drew near a realm where “love is art, and art is a variation on love.”

Between Love and Creation, He Became Both God and Beast

Social light and domestic shadow

At thirty-seven, while working on stage designs for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Picasso met dancer Olga Khokhlova(then twenty-seven).

Seeing her from the wings, he felt each movement like lines leaping to life from a painting.

She was elegant, intelligent, and in a way unapproachable.

For Picasso, living then in a poor studio district, Olga seemed from another world. He was drawn to her refined sphere; she was captivated by his untamed talent.

They fell in love and, over her family’s objections, married.

At the Russian Orthodox Church in Paris, figures like Cocteau and Diaghilev stood witness. It is said Picasso remarked at the wedding, “It’s as if I framed my life.”

Olga led him into high society, and he answered with a neoclassical clarity—orderly contours, tempered color. A life with family brought a certain order to his work.

But perfect love did not last. Olga sought order; Picasso, freedom. Even after their son Paulo was born, the distance only widened.

For him, home was warmth—and also a cage that stifled creation. Quietly but surely, his brush began to seek beyond the frame of family.

Embraced by forbidden light — Marie-Thérèse Walter

At forty-five, Picasso met Marie-Thérèse Walter, then seventeen, in front of a department store one winter.

Approaching her at the hat counter, he is said to have told her, “You are going to change my destiny.”

Still girlish, bright as the sun and healthy, she melted at once the weariness that Olga’s cold elegance had laid upon him.

Their relationship began in secrecy, and soon “another home” took shape in the depths of his studio.

When Picasso painted her body, the tip of his brush seemed to breathe. Marie-Thérèse gave him softness and a sense of renewal; his works grew rich with golden sensuality.

A daughter, Maya, was eventually born to them, yet Picasso still could not divorce Olga, and the household moved forward in two layers.

By day he painted family portraits; by night, nudes of Marie-Thérèse. Love acquired the scent of sin, and his art flared even more vividly.

The woman who reflected an age of despair — Dora Maar

At fifty-five, the sound of war was already near. Spain had fallen into civil war, tension hovered even over Paris, and for artists the cruelty of the times made survival more urgent than romance.

It was then that Dora Maar (twenty-nine), a photographer—intelligent, multilingual, politically acute—appeared, stirring Picasso’s rational side.

He was drawn to her sharp gaze and, at the same time, afraid of it. Through the camera she observed him, developing even the darkness of his heart.

Drawn to one another, they fostered love in the eddy of wartime anxiety.

During this period Picasso painted Guernica—a response to the Nazi bombing of the undefended town, expressing the horror of war through the language of Cubism, a work that would become emblematic.

Dora documented its making. Screams on the canvas, reports of bombings, nightly news of death—she felt it all as pain and kept photographing through tears.

Picasso watched those tears quietly. To him, they were not merely sorrow but evidence of truth, fuel to keep the fire of art alight.

Those tears became eternal on canvas—Weeping Woman—a portrait that is both the tragedy of war and love at its limit.

Around the same time, Marie-Thérèse waited with Maya in the south of France. Picasso deliberately kept the existence of the two women ambiguous.

One night, as if by fate, they crossed paths in his studio. As they argued, Picasso is said to have laughed and told them:

“Fight it out. I’ll love whoever wins.”

At those words, Dora wept; Marie-Thérèse fell silent. Love ceased to be a contest and became only pain.

By the end of the war, Picasso’s relationship with Dora ended as well. She fell ill at heart and left him.

Where Love and Death Slowly Mixed

A house with brushes and children — Françoise Gilot

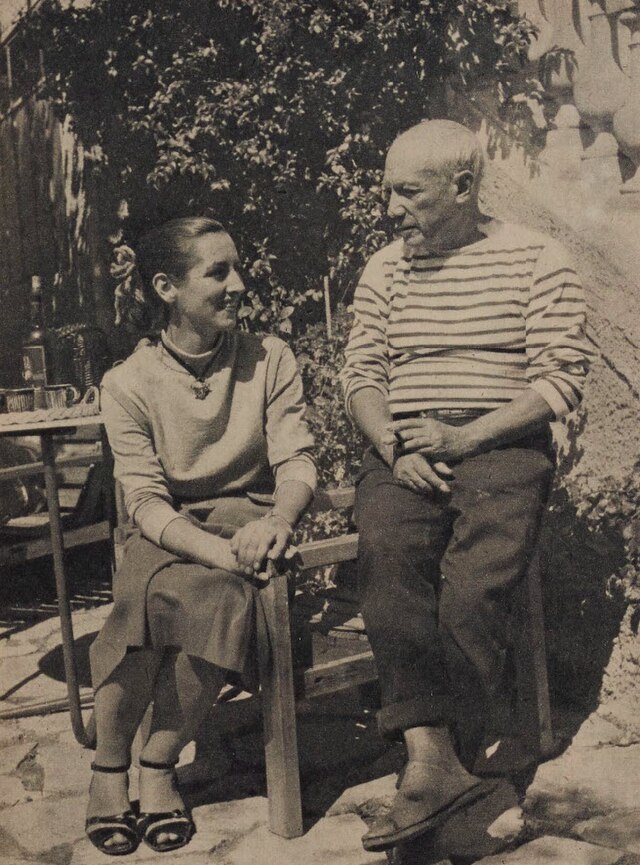

Around sixty, Picasso met Françoise Gilot (then twenty-one), a young painter introduced by friends. She was intelligent, strong-willed, with a quiet that kept others at a distance. Even in the instability after the war, she was a woman who intended to live by her own brush.

Picasso was drawn not to her youth or beauty but to the “power of resistance” that flowed within her.

Françoise, for her part, is said to have been attracted less by his “genius” than by his force of life—thinking that by his side she, too, might push something to its utmost. In her memoir Life with Picasso she wrote:

“I did not submit to him; I stepped into the storm.”

In other words, her relationship with Picasso was not “for him,” but a choice she made as part of her own life.

They moved to Vallauris in southern France and began a calm life under the sun. Their children, Claude and Paloma, were born, and laughter never left the studio’s corners. Soft lines and bright colors returned to his work; her presence gave him courage unafraid of aging and a new energy for creation.

But the happy days did not last long.

Picasso was a man who believed, “If you love me, give me everything,” while Françoise was a woman who wished to live without losing herself.

Gradually she felt that living with him was draining her own creative force; after ten years she left, taking their two children.

Deeply wounded by what he felt as betrayal, Picasso nevertheless did not blame her. Later he said:

“Françoise was the only free woman who loved me.”

There was a pride in that—like defeat. A love that began as a storm ended without ever reaching a quiet sea.

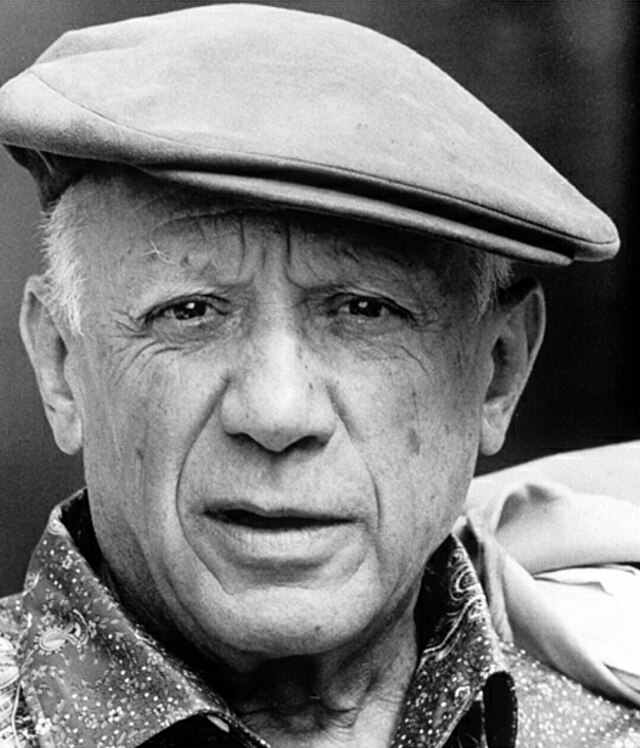

The Silent Muse — Jacqueline Roque

Past seventy, in the Madoura ceramics workshop at Vallauris, Picasso met Jacqueline Roque, then twenty-seven.

She worked at the atelier, speaking little, watching his work with a quiet gaze. Her silence was both comfort and mystery to him.

In this woman who stood by him not with words but with her eyes, he felt a “quiet love” different from his former lovers.

Unlike Fernande or Françoise, she did not insist on her independence; she simply entrusted herself to the rhythm of his creation. In her obedience he found relief, and could face his work without fearing his own aging.

They became lovers, and when Picasso was eighty and Jacqueline thirty-four, they married, making her his companion for life.

He drew her in hundreds of portraits—lines that held both the nobility of a goddess and the innocence of a girl. Jacqueline supported his late-life creation and shielded him from the surrounding clamor.

Even in old age, Picasso’s work mingled an unafraid fierceness with a quiet, fulfilled love.

Eternal blank space

The Last Color

In the spring of his ninety-first year, Picasso—as always—faced the canvas at his home in Mougins, southern France. The studio floor was flecked with paint not yet dry, and the walls were lined with dozens of variations on Jacqueline’s profile.

One night he invited Jacqueline and a few friends to dine. Pouring wine, he smiled gently and said:

“Drink to me, drink to my health, you know I can’t drink any more.”

Those words were his last. The next morning, Picasso passed away as if falling asleep. It is said his hand was still closed as though holding a brush.

After his death, Jacqueline buried him at the Château de Vauvenargues and planted white roses by the grave.

But later a family dispute arose over Picasso’s estate, and she was consumed by deep isolation and guilt. For thirteen years after losing him she withdrew from the world, and in the end took her own life, as if returning to him.

Marie-Thérèse Walter, too, lost her heart at Picasso’s death.

She was not invited to the funeral, nor included in the estate. Even so, she kept loving him, visiting the place where he lay and saying, “A world without him has no meaning.” Four years after his death, she quietly ended her life—as if following him.

What Was Pablo Picasso’s View of Love?

Picasso, who remade the history of twentieth-century art, was a man who lived for creation and love throughout his life. The loneliness of the Blue Period, the revolution of Cubism, the ceramics of his later years—women were always at their root.

For him, love was not reason but proof of being, and sex and creation sprang from the same well of life’s impulse.

Even in old age he kept falling in love, kept taking up the brush, and kept assuring himself he was alive by loving.

Perhaps he did not love “someone” so much as he loved the act of loving itself.

His paintings still illuminate the world like the afterheat of love burned to ashes.

What form of love do you feel in Picasso’s art?

日本語

日本語