Michelangelo’s View of Love|What Solitary Passion Burned in the Sculptor of God?

In the city of Florence, where light and shadow of the Renaissance intertwined,

a young boy once looked up at the sky as he walked the cobblestone streets — Michelangelo Buonarroti.

He was a man who carved souls into marble, painted the breath of God upon ceilings,

and searched for eternity within the realm of art.

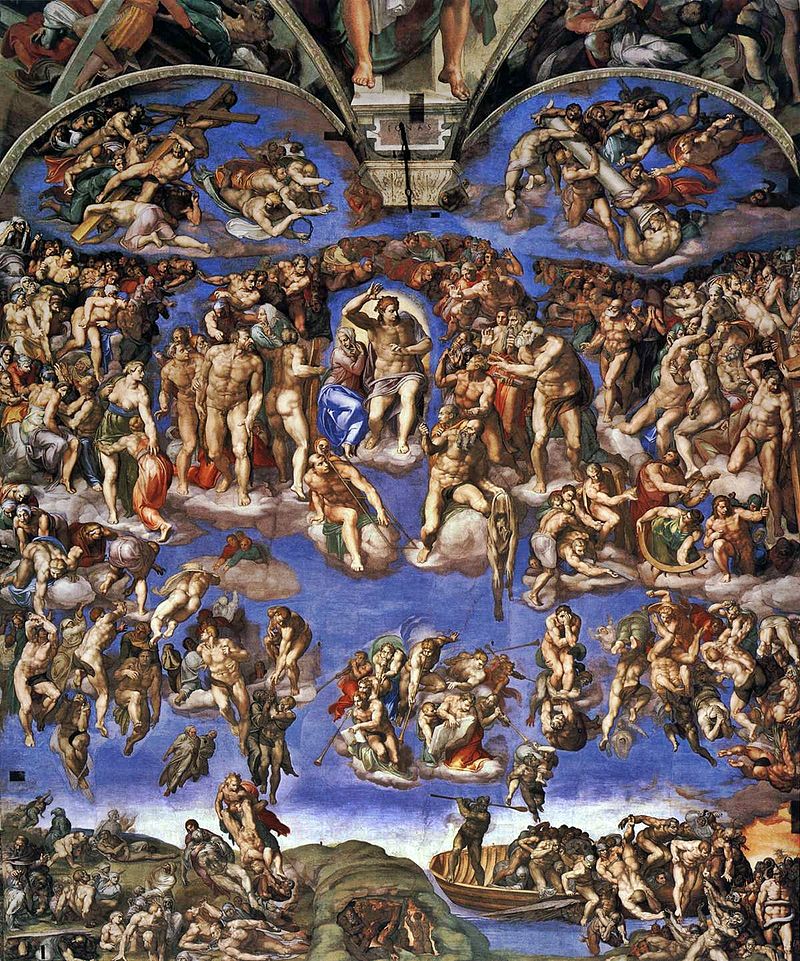

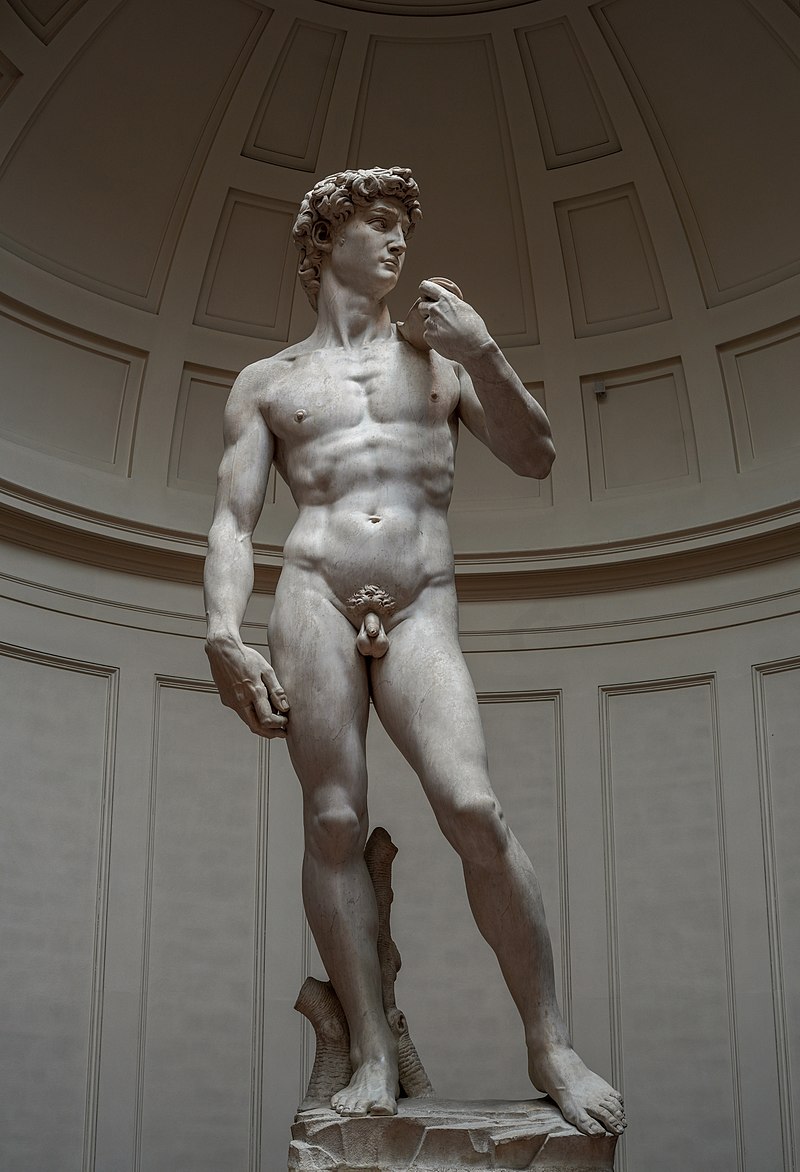

His masterpieces — David, the Sistine Chapel ceiling — remain symbols of humanity’s awe and devotion.

Yet behind that grand creation may have burned a quiet flame of love deep within his heart.

In this article, we cast light on the romantic sensibilities of Michelangelo,

tracing the emotional journey of a man who lived between beauty and faith, creation and desire.

Stone, Sky, and a Lonely Boy

The Son of a Stoneworker, Deprived of Parental Love

The Son of a Stoneworker, Deprived of Parental Love

Michelangelo was born in 1475, in the small village of Caprese, Italy.

His father was a somewhat self-important official, his mother died young, and the boy was raised by a “wet nurse of the quarries.”

—Later, he would joke, “I drank in marble dust with my nurse’s milk.”

Unfamiliar with the warmth of a real mother, he grew up touching stone. Perhaps this was the true origin of young Michelangelo’s sense of “love.”

A Fleeting Smile Etched on His Heart

In his teenage years, Michelangelo worked in the Ghirlandaio workshop, surrounded by older, rugged men.

Later, in the sonnets and letters he left behind, one can faintly sense a special fondness for his fellow apprentices and senior men at the workshop.

Perhaps a casual smile or a gentle hand from one of them left a soft flutter in young Michelangelo’s heart.

Fact is quiet, but imagination is gentle.

His introverted affections sank quietly into the depths of marble, known to no one.

The Light of Florence, the Shadows of Rome

The Crossroads of Art and Passion

At a young age, Michelangelo set out as an artist.

At 23, he completed the “Pietà”—the statue of Christ cradled by the Virgin Mary—a “sculpture of the soul” that mingled a yearning for motherhood with lost familial love.

In those days, he was surrounded by patrons and beautiful men and women.

But Michelangelo’s gaze was directed toward beautiful men.

The Genius and His “Beloved Disciples”

In his late twenties, there were young men rumored to be his “lovers.”

Among them, his disciples Aristodemo Gabbrielli and Gregorio de’ Sebastiani melted into his daily life—sometimes patrons, sometimes more than friends.

From their correspondence, one senses an ardent friendship, shadowed by something “not quite romance.”

Around this time, rumors of his “fondness for men” began to spread. But in Renaissance Italy, intellect and love often coexisted.

Perhaps what the genius sought was not physical love, but a “melding of spirits.”

A Hidden Love

Meeting Tommaso dei Cavalieri

In 1532, at age 57, Michelangelo met a young nobleman, Tommaso dei Cavalieri, through a friend in Rome.

Tommaso, then 23, shone among those around him, with his intelligence, beauty, and refined manner.

Michelangelo would later write to him, openly declaring,

“Since I met you, I have found a new soul within myself.”

Perhaps, as an artist and as a man, this was a moment when a completely new light shone into his life.

After those words, it is only natural to imagine that Michelangelo’s aging heart brimmed with a freshness and passion he had never known before.

A Wandering Chisel, a Hundred Love Letters

Michelangelo left behind over 300 poems in his lifetime.

Among them, those dedicated to Tommaso dei Cavalieri burn with particular heat.

“I am captivated by your beauty; my soul is yours.”

“Your eyes bewilder my chisel.”

“In the stillness of night, I carve your name.”

These are passionate phrases that rival even modern love letters—sometimes bold, sometimes graceful, and at times so single-minded they almost draw a smile.

“If I cannot be at your side, let me at least be a stone at your feet.”

A poignant wish unique to a master sculptor.

His feelings—wavering between art and love—were quietly inscribed on paper and in stone.

So intense were these passionate verses, it seems even his family grew somewhat concerned.

It is said that when Michelangelo’s nephew published his sonnets, he changed the pronouns in the poems to Tommaso from “he” to “she”—a “beautiful lie” for posterity.

In Renaissance Italy, a culture of affection between men was not itself remarkable.

Yet deep within Michelangelo’s heart, there may have been a “complex and somehow unfinished love,” unique to the artist.

The Blurred Boundary Between Art and Love

Love Sublimated into Art

In the marble Michelangelo carved, the shadows of beautiful young men he secretly admired are gently sealed away.

The “David”—an idealized body of youth—astonished and captivated the citizens of Florence.

The name of the model remains uncertain, but contemporary accounts and later poems hint at the names of young men Michelangelo cherished, such as Andrea Quaratesi and Fabiano di Bert.

What is intriguing is that, in Florence at the time, becoming a “model” for his sculptures or paintings was a quiet source of pride among young people.

To have one’s own body immortalized in eternal art—surely, that must have been an extraordinary experience even for those nameless youths.

Perhaps the grace that flows through his works was born from a blend of unreachable longing and the artist’s relentless curiosity.

Letters to a Widow, a Kiss That Never Reached

There are few women who stand out as “loves” in Michelangelo’s life.

Yet in his later years, he is said to have shared a close friendship with the poet Vittoria Colonna.

Colonna, a noble widow, was intelligent and deeply pious. The two exchanged sonnets and spoke of art and life until Vittoria’s death in 1547.

It is said he once kissed her hand, but could never bring himself to kiss her cheek—

Ascanio Condivi, his biographer, wrote that Michelangelo called this “the only regret of his life.”

Their relationship, perhaps, was more of a resonance between souls than of love in the usual sense.

To Michelangelo, women were not so much beings who stirred his heart with passion, but distant lights to be quietly revered.

The Twilight of Life, and the Love That Remained

Loneliness That Stayed Close in His Old Age

Even past eighty, Michelangelo continued to face stone.

In his quiet atelier, the faces of his disciples, young friends, and those who had lived in his heart since long ago seemed to gently sway.

In his last years, the one closest to him was Tommaso dei Cavalieri, to whom he had once given such deep affection.

Perhaps that presence gently warmed the old artist’s heart.

As the end of his life drew near, Michelangelo is said to have murmured,

“To have loved deeply—this is what made my art.”

Those words, it is said, carry a quiet pride even amidst loneliness.

What He Saw Beyond the Marble

Rome, 1564.

In the cold air of February, Michelangelo drew his last breath in his small room.

At his deathbed were his disciples and Tommaso dei Cavalieri—gentle witnesses to his life.

Though he had already set down his brush and chisel, his eyes, perhaps, were gazing far away—toward marble not yet seen.

“I am still unfinished.”

Leaving those words behind, Michelangelo ended his long journey.

With unfinished works and feelings he could never fully give, he quietly left this world.

His love, too, remains hidden within the marble, softly lingering as an afterglow.

What Was Michelangelo’s View of Love?

Michelangelo’s life was a journey where divine genius and human loneliness walked side by side.

The same hands that shaped the ideal of man in David and carved God’s wrath and mercy into The Last Judgment may also have carried a love that could never quite reach its destination.

For him, love was not something to possess, but something to pursue endlessly — a form forever in the making.

It was the warmth hidden within cold marble, the prayer that seeped into each brushstroke, the very act of asking, again and again, “What does it mean to be human?”

His love, though unfulfilled, took on eternal shape through art.

The beauty his soul sought beyond the body may well have been the truest form of his love.

And even now, that love seems to breathe softly — whispering someone’s name from deep within the marble.

日本語

日本語