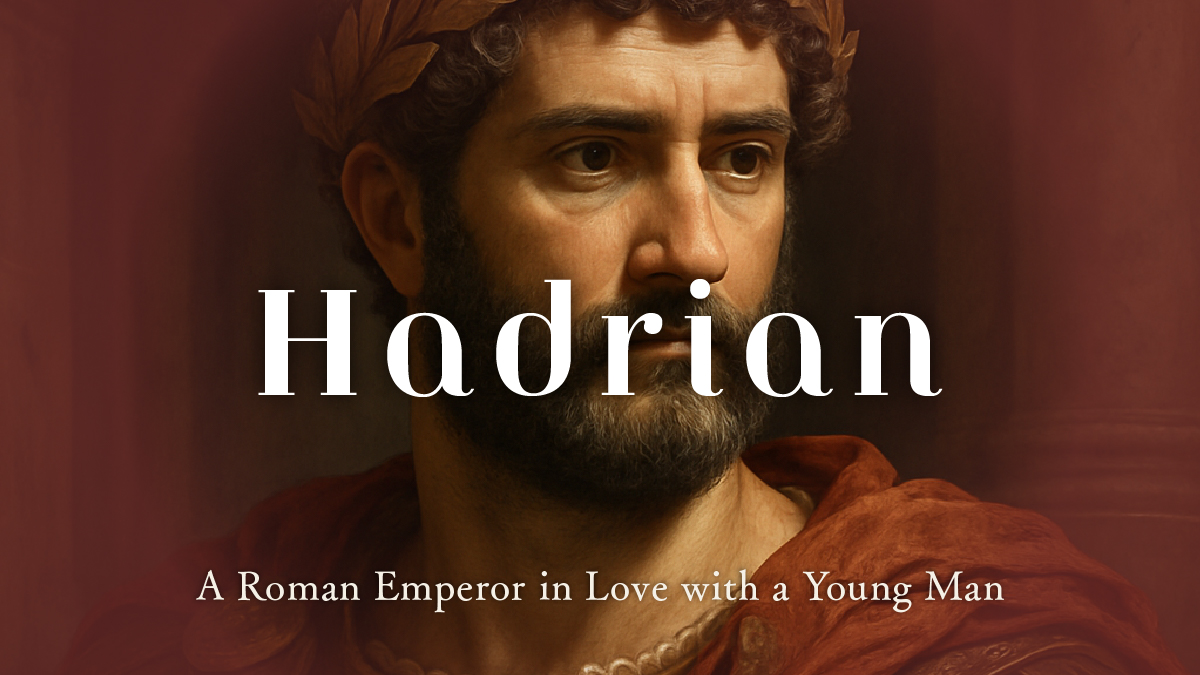

Emperor Hadrian’s View of Love|What Truth Hid Behind the Roman Emperor’s Forbidden Love?

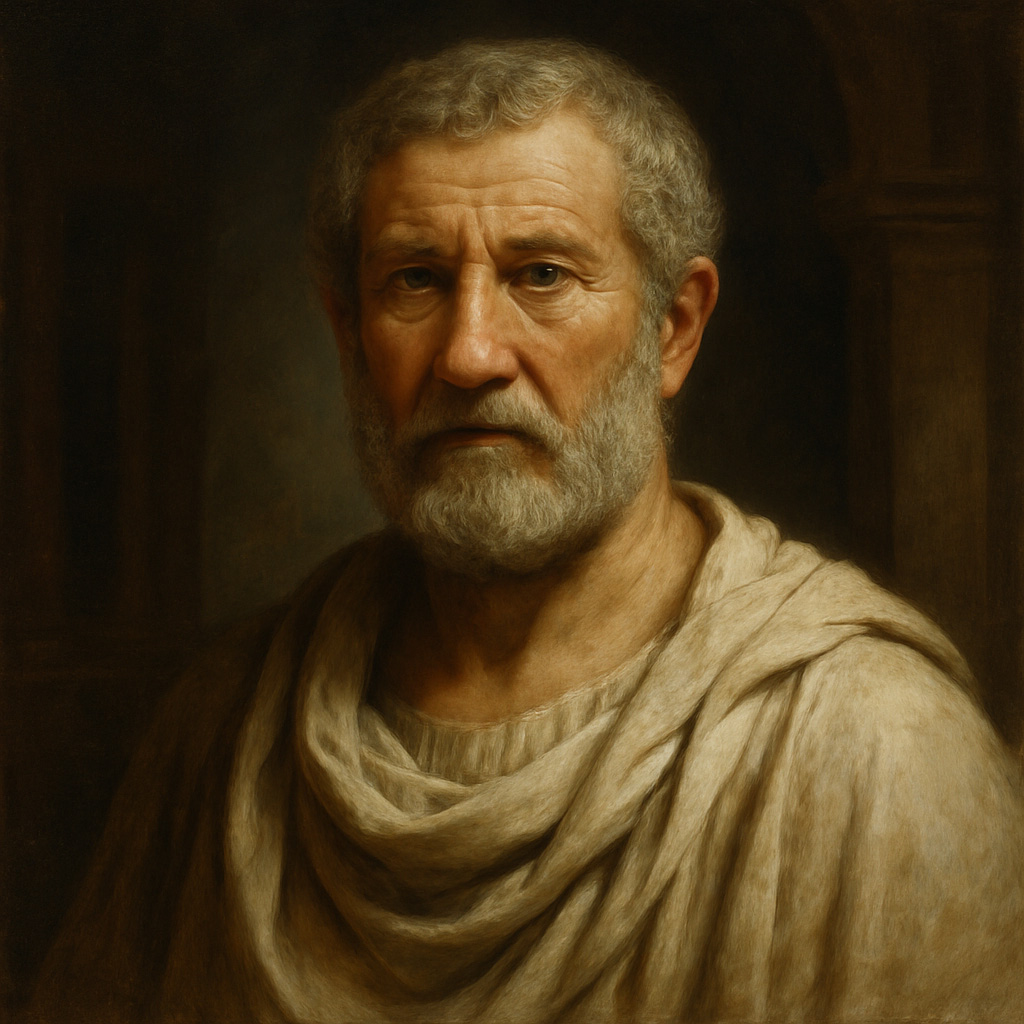

The 14th emperor of the Roman Empire: Hadrian.

Born in a small town on the Italian peninsula, he would one day rule over the world’s greatest empire.

Hadrian was an emperor who valued reason and aesthetics above the sword.

He rebuilt the Pantheon in Jerusalem and constructed “Hadrian’s Wall” in Britain—

Yes, he is a giant who always makes an appearance in the history textbooks.

Yet, what has carried his name across millennia is not merely the legacy of stone and iron.

In Hadrian’s life, there is another “story” to which everyone should quietly listen.

It is the story of his love for a beautiful youth—

Let us unravel the secret memory of a love that burned in the shadows of the empire’s glory.

The Loneliness of Childhood

A Boyhood Soothed by Learning

In 76 AD, in the wealthy Roman city of Italica in Italy, Hadrian was born.

He lost his father at a young age and grew up under the protection of Trajan (his future adoptive father, and later, emperor).

As a boy, Hadrian was drawn more to Greek literature and art than to swords and war.

Even when teased as “the Greekling,” he was enraptured by poetry, philosophy, and sculpture.

Reaching youth, Hadrian experienced military life—sharing food and shelter with soldiers on the frontiers, learning discipline and the realities of command firsthand.

There are no records of any romance from this period of his life.

But perhaps, in those lonely days, he sought his ideal of “beauty” within literature.

Love as an Emperor — A Hidden Romance in History

Succession and Marriage to Sabina

At 24, Hadrian’s life took a dramatic turn.

His adoptive father Trajan ascended to emperor, and Hadrian himself was saddled with the destiny of imperial succession.

Amid this pressure, he married Vibia Sabina, a noblewoman.

They met when Hadrian was in his early twenties and Sabina was probably in her mid-teens—a beautiful, dignified daughter from a distinguished Roman family.

A political marriage—such was the norm in the Roman Empire, where family name and power took precedence over personal happiness or the stirrings of the heart. Sabina, too, likely placed no hopes or dreams in her marriage to Hadrian.

Nevertheless, records suggest Sabina was intelligent and independent, never forgetting her pride as empress. It’s said she earned the respect of Roman citizens and devoted herself to public works and charity.

But what of them as husband and wife?

Hadrian was a just and rational emperor in court, but is said to have been taciturn and cold at home.

Sabina was reportedly pained by her husband’s indifference and emotional distance; some anecdotes even say she lamented to those around her, “My husband does not love me.”

Still, in public, they continued to play the part of the ideal “emperor and empress.”

They had no children, and in time, a gulf of feeling opened between them, but Sabina fulfilled her duties as empress to the end, maintaining her dignity and intelligence while living life in her own way.

Though they never truly became close as a couple, Hadrian never compromised Sabina’s honor or position.

Their marriage was one where they did not meddle in each other’s affairs, maintaining an “adult distance”—

A reflection of two people buffeted by the tides of their era and station.

An Emperor of Action and Aesthetics

Hadrian is known as an “emperor of the field.”

He never rested content in the Roman court, but traveled tirelessly across the empire, speaking directly with soldiers and locals.

At times, he even concealed his identity to observe the lives of commoners, so great was his curiosity.

Even in the camps, he was never without his books of art, poetry, and philosophy—often unfurling scrolls in a corner of his tent, gazing at the stars in contemplation.

Hadrian was not only a ruler who eschewed brute force for reason, but also a cultured emperor who cherished Greek civilization’s intellect and beauty.

His rebuilding of the Pantheon and the construction of Hadrian’s Wall were not just military or religious works, but are remembered as urban designs breathing his aesthetic sense and rationalism.

A soldier’s rigor, and an artist’s sensitivity—

This duality is what made Hadrian a truly singular emperor.

Secrets and Light, and Endless Loss

Fate Encountered on the Road

One day, the “travelling emperor’s” life was changed by an unexpected meeting.

Around 123 AD, while Hadrian was traveling in Bithynia—the region in Asia now western Turkey—he met a beautiful boy who would quietly, yet decisively, change the course of his life.

His name was Antinous.

At their first meeting, he was still a youth of about fifteen, with innocence lingering on his features.

Antinous captivated Hadrian not only with his looks, but with an inner sensitivity and quiet intelligence.

From the moment they met, something beyond words flowed between them.

The two became traveling companions—whether at feasts, on hunting nights, or even in the Roman baths, they were always by each other’s side.

Everyone at court noticed their closeness.

In Roman society, the mental and physical bonds between an older man and a youth could sometimes be praised as “virtue,” but for an emperor to uphold such a love required immense resolve.

Before long, their relationship became fodder for salacious gossip.

“The emperor is obsessed with a beautiful boy”—

Such rumors soon spread through the cobblestone towns. Yet Hadrian did not flinch; he continued to choose time with Antinous.

Hadrian dedicated poetry to Antinous, had statues made, and even stamped his beauty on coins.

A ruler of the empire and an obscure youth—thirty years apart in age.

Yet, between them, a quiet intimacy blossomed that transcended status and social norms.

Sometimes Antinous gazed at Hadrian with anxious eyes, at other times with a pure smile.

Surely, the emperor’s heart was being filled by a void greater than the breadth of the empire itself.

The Tragedy on the Nile

A Roman emperor and a beautiful youth—

Their journey would come to an unexpected end in Egypt.

In 130 AD, Hadrian and Antinous set off on a journey up the Nile. It is said that on a night when the full moon rose over the pyramids, gentle ripples spread across the Nile’s surface.

But happiness could not last forever.

That year, at the tender age of eighteen, Antinous drowned himself in the Nile.

The reason for his death remains shrouded in mystery.

“Offered as a sacrifice to the gods.”

“Took his own life out of absolute love for the emperor.”

Many theories swirl, but the truth is lost to darkness. Each story is tinged quietly with grief and love.

It is said that upon hearing of Antinous’s death, Hadrian wept openly without hiding his sorrow. Perhaps it was the first and last time the master of the empire shed tears before others.

In his grief, Hadrian built a city named “Antinopolis” in Antinous’s honor, and officially declared Antinous a god.

For a Roman emperor to “deify a beloved” was an extraordinary act.

To make a loved one into a god—

Perhaps that was the shape of love for Hadrian, both a man of power and a solitary soul.

Loneliness in Old Age—Echoes of Love and the Emperor’s Twilight

“Emptiness” at the Summit of Power

Having lost Antinous, Hadrian seemed to have left his former vigor somewhere behind.

Not the vast territories of the empire, nor treasures of gold and silver, nor even the court’s bustle that once adorned him—none could fill the emptiness in his heart.

In politics, his cool rational judgment remained, but in old age, Hadrian was enveloped in a shadow of loneliness.

He immersed himself in poetry and architecture, spending his days chasing the traces of Antinous.

His relationship with Sabina grew cold; all that remained beside him were silent loyal retainers, and the smile of the beautiful youth carved in stone.

At times, he is said to have gazed at the moon alone in the palace at night. Perhaps more than anyone, he knew just how fleeting was the balance between what he had gained and what he had lost.

“I sought happiness, but I did not know what it was.”

These words, attributed to Hadrian, are tinged with the loneliness of an emperor and the longing for love as a human being.

In 138 AD, at the age of 62,

he succumbed to illness and quietly accepted the end of his life.

There is no record of whose name he called in his final moments.

What Was Emperor Hadrian’s View on Love?

Hadrian’s life was a delicate tapestry woven from reason and passion, beauty and solitude.

Behind the intellect that rebuilt the Pantheon and restored order to an empire, there may have dwelled a man quietly yearning for love.

As emperor, he held the world in his hands. Yet when he lost the one he loved, he discovered—perhaps for the first time—that there are things even power cannot command.

By deifying Antinous, was he trying to preserve love for eternity, or to pray against the ache of loss?

For Hadrian, love was not something to possess, but something to leave behind—something meant to outlast time itself.

And you—when you lose the one you love, will you try to forget?

Or will you, like him, carve that love into eternity?

日本語

日本語