Schrödinger’s View on Love|A Marriage as Free-Spirited as a Cat

Many people have heard the phrase “Schrödinger’s cat.” The cat that is said to be both alive and dead has become known as a strange symbol of the uncertainty inherent in quantum mechanics.

And the creator of this thought experiment was the theoretical physicist Erwin Schrödinger. Having formulated the wave equation and won the Nobel Prize, he stands as a giant whose name is firmly engraved in the history of science.

But did you know that his private life was filled with forms of love that lightly skipped over the boundaries of common sense?

In this article, we follow Schrödinger’s journey from his childhood to his later years, focusing especially on his view of love.

I would be delighted if you come to know another side of Schrödinger—one that never appears in the pages of history textbooks.

Light and Shadow of Childhood

A Quiet Home and a Springlike Gaze

In 1887, in Vienna—the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—Schrödinger entered the world as if bathed in soft, gentle light.

His father was a botanist, the kind of man who would peer through a loupe and become absorbed in the delicate structures of spores. His mother, the daughter of a chemistry professor, possessed a sensitivity that allowed her to speak of minerals and crystals in poetic language.

In this household, questions such as “Why does a rainbow curve?” or “Why is the underside of a leaf rough?” may have flowed as naturally as dinner conversation.

Growing up in that environment where theory and sensibility blended seamlessly, young Schrödinger would sit cross-legged on a chair, silently listening. He spoke little, but his eyes moved constantly—such was the kind of child he was.

The Observer Born in Silence

Schrödinger’s boyhood is often described as “quiet.” But that quietness was far from empty.

He would pull Goethe’s poetry collection from the bookshelf and observe the marching rows of ants in the grass—moving back and forth between observation and imagination as if they were a single breath. Behind his glasses, his eyes did not merely look at the world; they seemed intent on absorbing it whole.

He had few friends, yet he was never lonely. Plants, stones, particles, and even silence itself were always beside him.

The adults around him watched over him as though he were something sacred. The prototype of the man who would later describe the world using the precise language of physics was already forming quietly—and unmistakably—during these years.

The Beginning of a Young Love

The Lingering Echo of First Love

At fourteen, Schrödinger found his heart stirred for the first time by a girl a few years younger who attended the same school. In his diary she appears under the name “Rella.”

Whenever they passed each other in the classroom or the hallway, he would quietly let his gaze rest on her. His introverted nature likely kept him from ever putting his feelings into words.

There is no record of whether they ever truly spoke, and their relationship never developed into a romance. The feeling lived only within him, growing and ending in silence—his solitary first love.

We cannot know exactly what traces this gentle infatuation left within him.

Yet, considering that he later showed a recurring, particular interest in “young girls,” this quiet emotion toward Rella may indeed have held special meaning for him.

A Broken Engagement

At twenty-four, working as a physics assistant at the University of Vienna, Schrödinger spent his days absorbed in lectures and research—but his heart was deeply occupied by a different thought.

It was a secret, fervent love that had begun with his meeting Felicie Kraus, a girl nine years his junior.

To support himself, Schrödinger also worked as a private tutor, and Felicie was one of his pupils. Raised in an eminent Catholic family, she possessed both refinement and intelligence, and she quickly stood out to him as someone special.

His diary from that time contains scattered fragments about Felicie—quiet entries in which his feelings toward her subtly shimmer between the lines.

Though formal engagement was forbidden, the two continued to meet in secret, eventually becoming committed enough to pledge their future to one another.

But the relationship ended when Felicie’s mother, Johanna, vehemently opposed it. Her family refused to accept Schrödinger as a son-in-law, deeming him a poor match lacking stable income or social standing.

Unable to pursue marriage, Schrödinger fell into such despair that he even considered abandoning physics altogether to take over his father’s factory.

In the end, through his father’s persuasion and his own inner resolve, he returned to the path of research—leading eventually to his important publications.

This quiet farewell etched a deep shadow into Schrödinger’s inner life and would cast a long, subtle influence on the forms of love and choices that shaped the rest of his years.

A Contract of Love and Liberation with Annie

The Beginning of Resonance

Around the age of twenty-five, Schrödinger was staying in a mountain village called Seham in northern Austria, partly for recuperation.

For someone often in poor health, the clear air and gentle climate brought rest not only to his body but also to his mind. Under the pretext of observing atmospheric electricity, he would look up at the Alpine sky and momentarily forget about the self tethered to the ground.

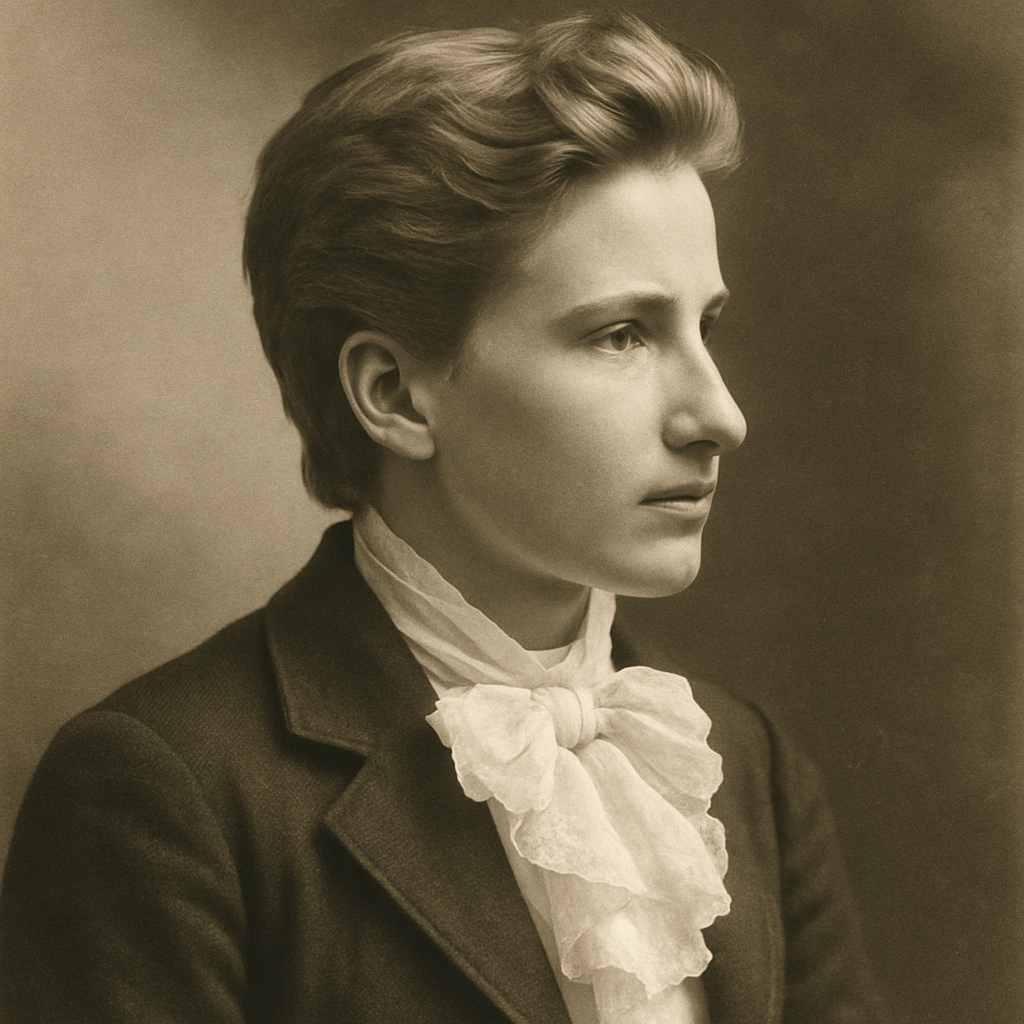

One day, he met a sixteen-year-old girl who was staying in the village as a caretaker for a friend’s children.

Annemarie Bertel. People called her Annie.

She was a girl who did not like drawing attention, yet somehow carried a kind of transparent light around her. Their encounter did not include any dramatic moment. Rather, their time simply began to intersect little by little, as though melting into the mountain light.

That love eventually blossomed was, in a way, entirely natural. Annie prepared meals for the often-ailing Schrödinger, stayed quietly beside him when he was tired, and in that silence gently unraveled the knots in his heart.

Before he knew it, Schrödinger had entrusted his thoughts—his very heart—to Annie. Her presence was the first that made him feel it was “safe to share himself.”

And seven years later, at the age of thirty-two, he married Annie and found a lifelong partner. It was less a public institution and more an inner, quiet vow between the two.

An Experiment in Open Marriage

To Schrödinger, marriage may have been less an institution and more a kind of spiritual laboratory.

After marrying Annie, he consistently regarded “monogamy” as a bourgeois illusion and continued to practice forms of love that transcended that framework.

The two mutually allowed each other romantic or emotional relationships with others. In other words, it was an open marriage.

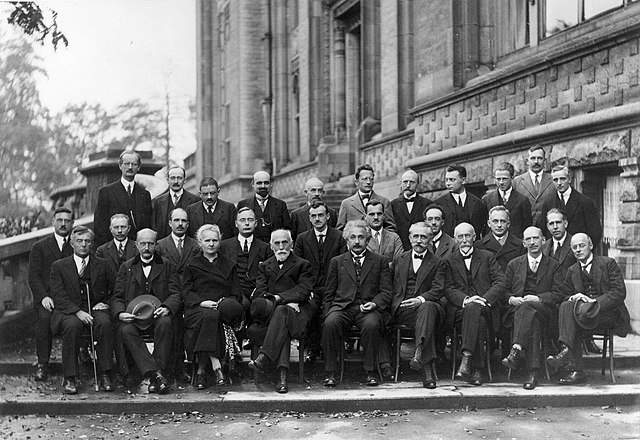

There is even an anecdote that once Schrödinger lost sexual interest in Annie, she helped him search for a suitable lover. It is also known that Annie herself entered into a romantic relationship with the mathematician Hermann Weyl.

The reaction around them was chilly, but Schrödinger brushed it off and said:

“In my life, I want to be honest with the truth. The same applies to love.”

For him, sincerity did not mean conforming to social forms, but following his own sensitivity and ethics. His philosophy allowed probability and fluctuation in love just as it did in the indeterminacy of physics.

It was in the midst of this life that he published the wave equation, bringing a revolution to the world of quantum mechanics. It was almost as though he had translated his own philosophy of love into mathematical form.

Waves overlap, intersect, and pass through one another without merging.

That uncertainty is what makes them true, and beautiful—

and within that fluctuation, he and Annie found their own kind of sincere resonance.

Dangerous Desires and Social Condemnation

Longing for Innocence and Transgressive Desire

When thirty-nine-year-old Schrödinger was working as a tutor in Berlin, his gaze turned toward a fourteen-year-old student, Ithi Junger.

The age difference lay between them like a deep gorge, but he crossed it with ease.

By the time she turned seventeen, their relationship had become that of lovers, and eventually it led to pregnancy, an abortion, and their separation.

Here, the underlying “longing for innocence” that fueled his romantic worldview is laid bare.

His diary Ephemeride records the words:

“For an intellectual genius, a young and innocent girl is the ideal companion.”

It is a line that dangerously turns desire into philosophy—a justification with an ominous ring.

Later, he became involved with Hildegunde March, the wife of physicist Arthur March, and after turning forty, he fathered a daughter, Ruth.

The bizarre three-way cohabitation—housing his wife Annemarie and Hilde under the same roof—became a scandal in British society, drawing attention and criticism, and casting a shadow over his reputation.

The idea of cohabiting with both wife and lover, like a quantum superposition, defied common sense—yet to him, it was merely a natural extension of his view of life.

A New Form of Love in Dublin

When the shadow of Nazism grew darker, he fled the country and eventually arrived in Dublin.

While he continued his research as director of the Institute for Advanced Studies, his heart remained ever drawn to women.

He met the Irish actress Sheila May when he was fifty-six; she was in her mid-twenties, wrapped in the youth and radiance of the stage.

A daughter was born between them, adding a new weight to his life in exile.

Over time, however, a distance began to form.

Between a woman who lived on stage and a man absorbed in research, an unbridgeable gap slowly widened. Their daily rhythms ceased to mesh, and the relationship came to a quiet end.

Several years later, through acquaintances in Dublin, he met another woman—Kate Nolan.

Unlike the actress Sheila, Kate did not belong to the glamorous world of the stage but rather to local cultural circles and warm, domestic spaces. She was around thirty, with a calm demeanor and simple charm, and is said to have offered Schrödinger not intellectual stimulation but the warmth of everyday life.

Their relationship began as friendship.

But as she came to understand and support him—a lonely exile—the bond quietly shifted into intimacy.

He had a daughter with Kate as well, and Schrödinger’s life became a tapestry of overlapping threads: research, romance, and family.

The Gentle Light That Remained in His Final Years

The Sublimation of Love and the Afterglow of Poetry

Through his relationship with Kate Nolan, Schrödinger entered a time when the once-blazing fires of his passions gradually settled.

With age, his love grew quieter, as if avoiding the public eye; the passion he once directed outward turned inward, becoming contemplation.

He devoted himself to poetry and philosophy, trying to give shape to his own life.

The perilous longing he once held for young girls in his youth was, in later years, transformed into a tranquil symbol—no longer sensual, but a space of spiritual nuance.

By his side in his final days was his wife Annie. She remained with him to the end, accepting the complex shape of his heart—where love and freedom blended—without denying it.

At seventy-three, Schrödinger passed away quietly in Vienna.

Though he was a giant who laid the foundations of quantum mechanics, as a man he continued to cast himself into the uncertain waves of love.

His life ended holding both scientific and erotic “indeterminacy.”

In the end, he was like a wave—layers of emotion superimposed—gradually dissolving without a sound.

What Was Schrödinger’s View of Love?

Looking back on his life, we see that equations and romance always ran side by side.

His open marriage with Annemarie, his cohabitation with Hilde, his relationships with Sheila and Kate in exile—all were condemned by society, yet he walked his own path.

For him, love was an “energy source” that transcended systems and ethics.

It is not impossible that the passion behind the wave equation was born from the same impulses as his love affairs. His longing for young girls and his unrestrained relationships—all likely served as forces driving his thinking.

To him, love and marriage were not things to define but things that wavered each time one observed them.

If someone were to ask, “Is marriage something only two people share?”

Schrödinger might answer:

“Until you open the box, maybe it’s three people… or maybe no one at all.”