Dante’s View of Love|What Eternal Love Inspired the Poet of The Divine Comedy?

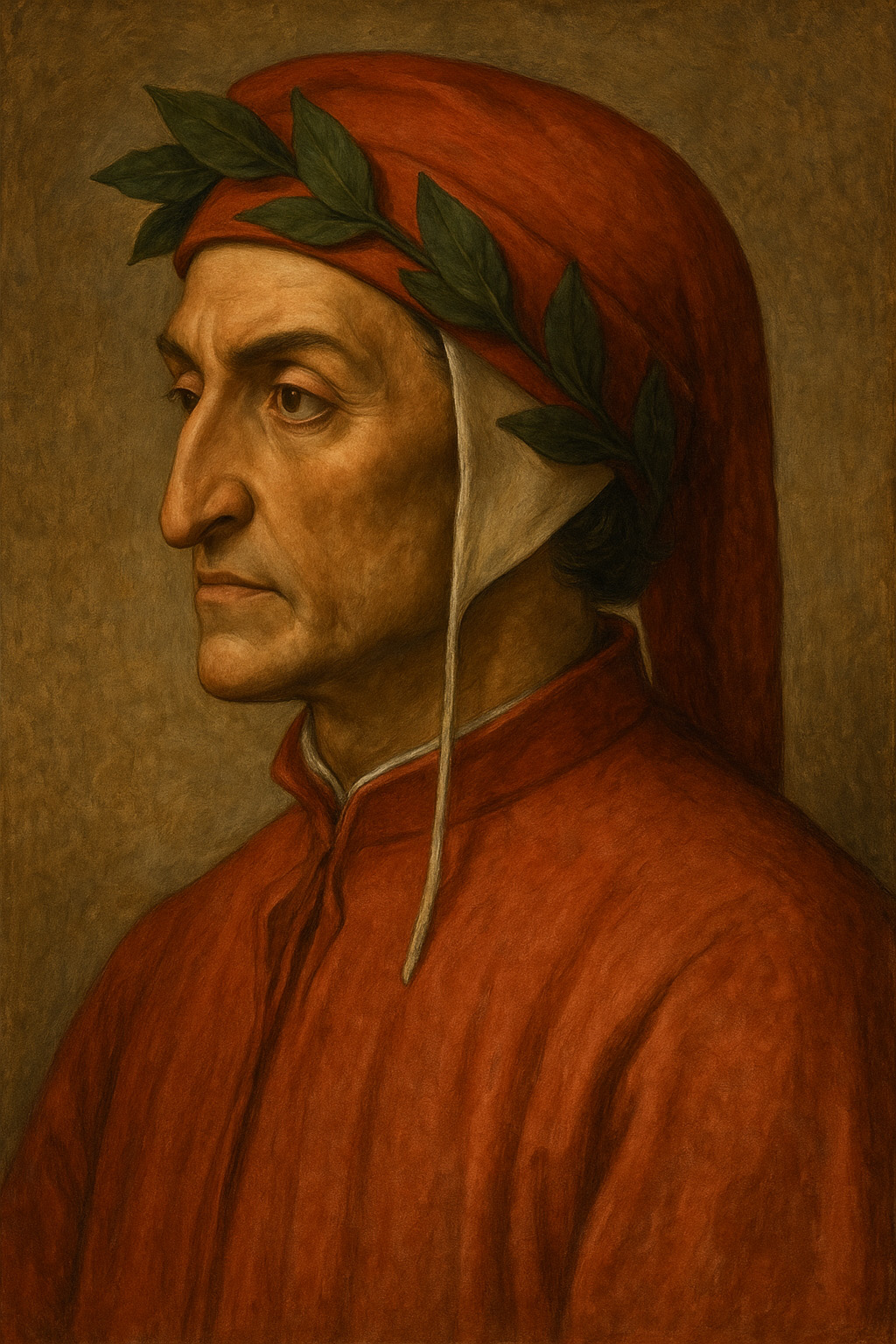

Dante Alighieri.

A towering figure who symbolizes medieval European literature and stands among the greatest in the history of world letters.

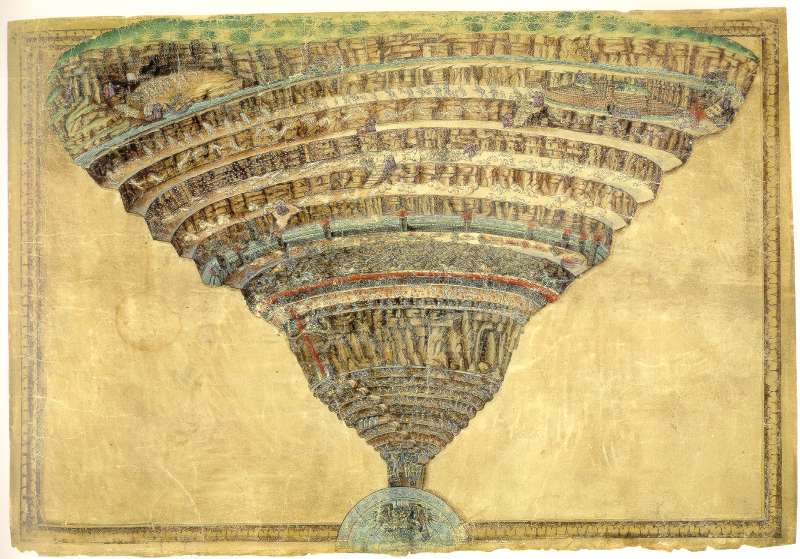

The long narrative poem that immortalized his name, The Divine Comedy, is a grand tale of a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven—but his guide on this journey was not merely a fictional literary creation.

She was the woman who ruled his heart for his entire life.

Dante was also active as a politician, but was swept up in the factional strife of Florence (the conflict between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines) and was exiled from his beloved city.

His life in exile was cold, hungry, and deprived of the warmth of close friends, yet in the softest corner of his heart, her image always glowed.

Though his love never once came to fruition in reality,

it was powerful enough to make him a poet—and to change the course of literary history.

Childhood and a Fateful Encounter

Born in the Light and Shadow of Florence

In 1265, Florence’s stone-paved streets reflected the summer sun, and from deep within its alleys came the scent of fresh bread and olives.

Yet at the same time, tension from political rivalries gripped the city squares. Merchants, poets, and soldiers alike were tossed about by the waves of the age.

Born into a wealthy family, Dante studied Latin, theology, and classical literature from an early age, and was already familiar with poetry.

His gaze wandered beyond the written words in his books, searching for “something deeper.”

He did not yet know what that was—until one day, at the age of nine, the answer appeared before him.

The Banquet of Fate

At a May festival banquet hosted in the home of Folco Portinari, a wealthy banker and acquaintance of his family, she appeared—a girl named Beatrice Portinari, clad in a pale pink dress.

She, too, was born to a prominent Florentine family, and was about the same age as Dante.

Hair like captured sunlight, translucent eyes, and the faint shadow on her cheek when she smiled—in that instant, a new sovereign quietly took the throne within the nine-year-old boy’s heart.

Years later, in his poetic autobiography La Vita Nuova, Dante would write:

“From that day forth, my heart was the faithful servant of Love, my sovereign.”

This was no exaggeration. That meeting had set the course of his life.

The Distant Observer

A nine-year-old boy had no courage to speak directly to the girl he adored.

Instead, he learned to simply “observe” from afar.

The sway of her dress’s hem as she walked,

the subtle movement of her fingers,

the precise curve of her lips when she laughed—

He stored each of her gestures in a secret drawer within his heart, occasionally taking them out to polish them.

By modern standards, it might seem an unsettling kind of staring. But in the Middle Ages, such devotion was seen as the virtue of the courtly poet.

By not touching, love would never decay, and could be preserved in its ideal form—

like a piece of glass art left in the sunlight, admired only from a distance.

That was Dante’s first love.

Youth and the Rekindling of an Impossible Love

The Reunion in White at Eighteen

Years passed. At eighteen, during a festival day in Florence—

The streets were decorated with herbs and flowers, stalls lined the banks of the Arno, and the air was filled with a mix of prayers and laughter.

In the crowd, Dante saw her again—Beatrice, dressed in white.

The moment she smiled and bowed slightly—

the sounds of the world receded, leaving only the beating of his own heart and the sound of light gliding across the river.

In La Vita Nuova, Chapter 3, Dante recalls this meeting:

“A sweetness and trembling, unlike anything I had ever known, passed through the depths of my soul.”

In reality, they exchanged only brief greetings and a few words,

yet those words left an indelible mark upon his heart.

Separate Marriages and Parallel Lives

In Florence at the time, marriage was more about alliances between families than personal affection.

Beatrice married the wealthy banker Simone de’ Bardi,

while Dante married Gemma Donati, daughter of the noble Donati family, when both were around twenty.

Though they lived in the same city, their only encounters were fleeting, at religious ceremonies or public festivals. There were no letters, no secret meetings—always a careful distance.

Today, one might call it quietly “pining from afar,” but at the time it was praised as a “noble, temperate love.”

It is said that Dante even feigned affection for another woman to divert suspicion from Beatrice.

This was a technique known as schermo (“screen” or “veil”)—a medieval courtly tradition of using a “decoy lover” to hide one’s true feelings.

In a city as rife with gossip as Florence, Dante took every precaution to keep his ideal love unsullied.

Preserving Her in Poetry

Because he could not touch her in life, Dante embraced her in poetry.

In La Vita Nuova, Beatrice appears as la gloriosa donna della mia mente—“the glorious lady of my mind”—a heavenly guide.

Her greeting is a sacred rite of salvation, her smile a divine light that lifts the soul upward.

For example, in Chapter 26, Dante recalls the day they first met with such precision—down to the colors and scents—that he writes:

“Her appearance spoke to me with the words of an angel, issuing quiet commands.”

It was an ideal of love entirely removed from physical desire, approaching the religious.

Family and Duty — Life with Gemma Donati

A Marriage Born of Strategy

Dante’s marriage was less about love and more about uniting two houses. The engagement was arranged in childhood, with the actual wedding taking place in his youth.

His wife Gemma was said to be modest and honor-bound.

She appears rarely in his poetry—not necessarily because of a lack of affection, but because his verse was devoted to his idealized love for Beatrice.

That silence itself spoke of the depth of his one-sided devotion.

Children and the Father’s Legacy

Records suggest Dante and Gemma had at least three, possibly four children:

Pietro, Jacopo, Antia, and possibly a younger daughter named Beatrice (whether by coincidence or intention, we do not know).

This younger Beatrice is said to have entered a convent at an early age, taking the name Sister Beatrice.

Even though his children remained in Florence under Gemma’s care after his exile, they later played a role in preserving his work—both Pietro and Jacopo compiled and annotated his poetry.

The Intersection of Reality and Ideal

A contemporary noted that when Dante spoke of Beatrice,

“he looked as though he were a monk in prayer.”

One anecdote reveals his vulnerability:

Friends once took him to a wedding feast to lift his spirits, only for Beatrice to appear among the guests.

At once his heart pounded, his body shook, and he had to lean against the wall to remain standing.

Noticing his state, the ladies began to whisper and giggle—even in Beatrice’s presence.

Humiliated, Dante left the celebration in tears.

Early Farewell and the Birth of The Divine Comedy

Beatrice’s Death and the Silence

In 1290, when Dante was 24, Beatrice died at the age of 25—likely of illness.

The news shattered him.

“I have lost the most beautiful star upon the earth.”

He wandered Florence in grief, ceasing to write for a time.

But eventually, he made a vow: there was one way to keep her alive—

to enshrine her forever in poetry.

The final chapter of La Vita Nuova ends with his promise:

“I will write of her what has never been written of any woman.”

This vow would be fulfilled decades later in The Divine Comedy.

Exile and the Shape of Love in Dante’s Later Years

Days of Wandering Born from Political Strife

In 1302, in the midst of Florence’s political turmoil, Dante, a member of the White Guelph faction, lost power and was sentenced to permanent exile.

“If you wish to return, you must pay an enormous fine and make a humiliating public apology.”

Such were the conditions, but he refused them outright.

The proud poet chose to abandon his homeland forever rather than return shrouded in disgrace. From then on, he drifted through Italy—Verona, Lunigiana, and finally Ravenna—

living under the patronage of noble families, continuing to compose poetry and political treatises.

It is said that, on winter nights in dimly lit inn rooms, he would sometimes see Beatrice’s smile flicker in the lamplight as he bent over parchment.

Distance and Respect for His Wife, Gemma

During his exile, there is no record of Dante ever living again with his wife, Gemma Donati.

No letters between them survive either—likely not from a lack of affection, but from the distances created by circumstance and the era.

His family remained in Florence, while his own life unfolded in foreign courts.

Even so, he never wrote a word of complaint about Gemma.

Perhaps his lifelong silence, while living far from his homeland, was his final way of showing her respect.

Sometimes, “leaving things unsaid” can be the deepest form of courtesy—

and Dante knew this well.

Peaceful Creativity and Memories in Ravenna

In his later years, Dante was welcomed as a guest by the Da Polenta family in Ravenna, where he enjoyed a tranquil courtly life.

He would wake to the sound of monastery bells, debate with his pupils in the garden, reread the classics in the afternoon, and by the fire at night, refine a new passage of The Divine Comedy.

One evening, a young pupil suddenly asked:

“Master, was Beatrice truly just an acquaintance?”

Dante is said to have narrowed his eyes with a brief smile and replied:

“The word ‘just’ does not suit love.”

It was neither a clear affirmation nor denial—

yet in his voice there was both the warmth of quietly cherishing the past and a trace of playful humor.

The Crystallization of Dante’s View of Love

The Poet Who Raised Love to the Level of Faith

In 1321, at the age of 56, Dante contracted an illness on the return from a diplomatic mission to Venice.

While crossing marshlands, he was struck by malarial fever. Even as sickness overtook him, he is said never to have stopped polishing the final lines of his poem.

On the night of his death, a half-finished manuscript lay at his bedside, and a young pupil read Latin prayers aloud.

His face bore a strange serenity—

perhaps, in his final moment, he saw both the gates of Heaven and Beatrice’s smile.

What Was Dante’s View on Love?

Dante’s love had scarcely begun in reality.

It was like a snowflake resting on one’s palm—melting if touched, yet keeping its perfect shape forever when left alone.

He continued to portray love not as physical union, but as a light guiding the soul upward.

In his mind, Beatrice ceased to be merely human and became a messenger of God, watching over him from beyond reality.

With Gemma, he built a household sustained by duty and respect, and their children inherited his literary legacy.

His real life and his ideal love never converged—

yet together, they formed the twin pillars that supported his life.

Love does not always have to be fulfilled.

Perhaps it is precisely the unreachable distance that gives birth to words and makes the soul tremble.

Dante spent his life answering this question through his poetry.

And his words still, even centuries later, light small flames in the hearts of those who read them.

Those flames quietly teach us that the pain and the joy of loving someone from afar are, in truth, the same color.

日本語

日本語