Exploring the Grimm Brothers’ View of Love | What Forms of Love Were Hidden in Their Fairy Tales?

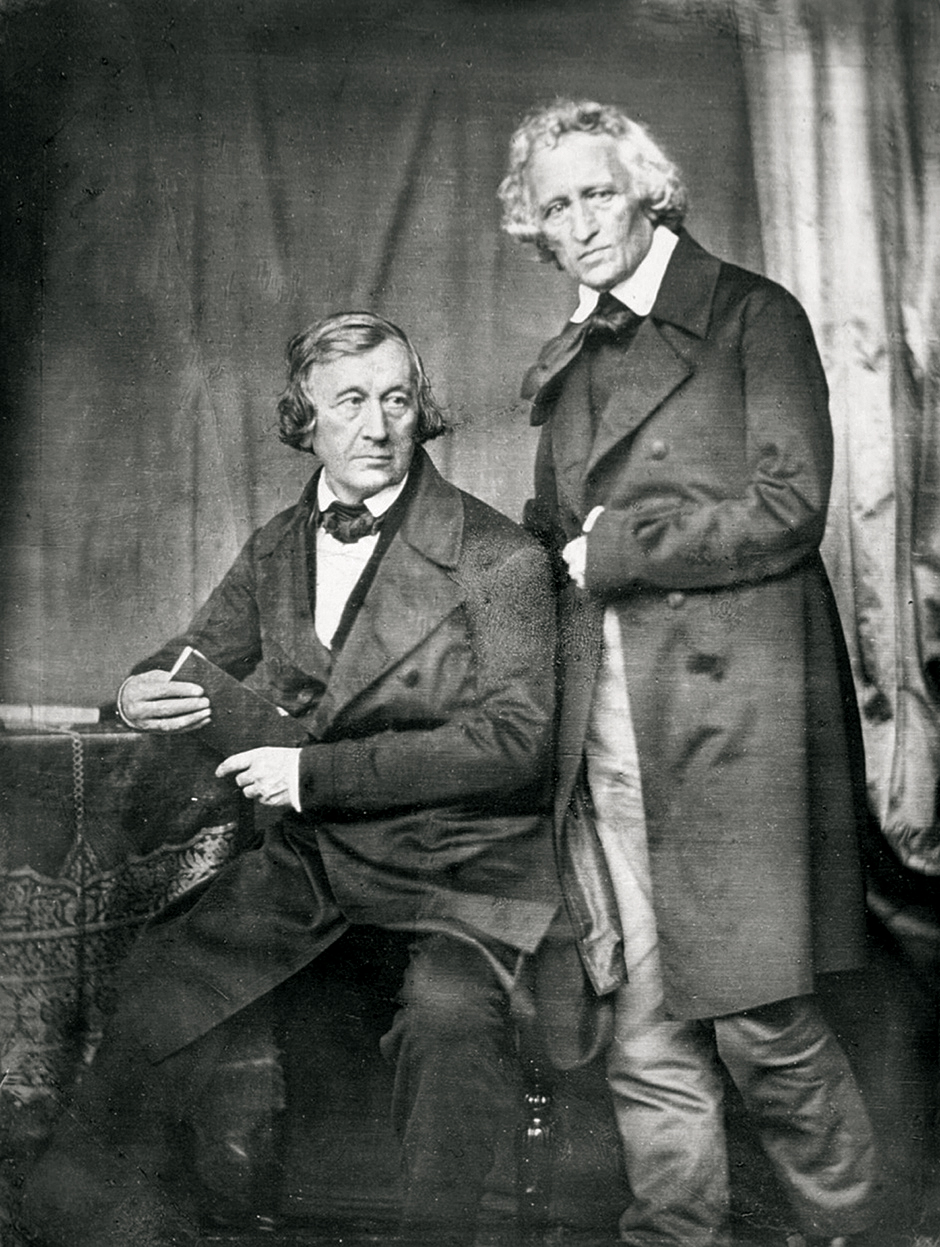

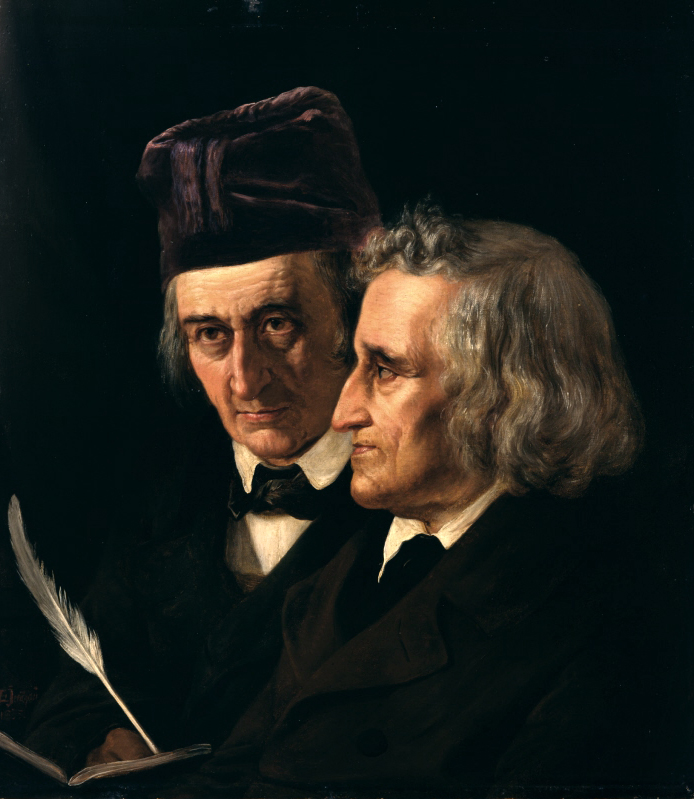

The Brothers Grimm.

When we hear their name, what first comes to mind is likely a delightful collection of fairy tales, adorned with colorful illustrations.

Yet Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm—who also left an immense legacy as linguists—were quiet giants who patiently gathered the words and soul of the German people.

When we trace their lives using “love” as a guiding line, however, something emerges that can never be found in textbook descriptions: a passion that was deeply awkward, yet astonishingly pure.

In this article, I would like to carefully revisit their journey from childhood to their final years, and in doing so, unravel the singular and unconventional view of love they upheld throughout their lives.

As if dusting off shelves of history steeped in the scent of ink and time, I hope to offer a glimpse of the deeply human faces of the Grimm brothers—faces rarely captured in textbooks.

Sheltered by the Quiet Forest

In the Stillness of Hanau

In the early winter of 1785, in the quiet town of Hanau in central Germany, Jacob Grimm was gently welcomed into the world. The following year, as if following closely in his brother’s footsteps, Wilhelm was born. From the very beginning, the brothers may have been destined to walk side by side.

Their father was a capable jurist with a stable income, and the family belonged to a relatively comfortable class for the time. Their mother, a well-educated woman, quietly sustained the household, tending carefully to her children’s daily lives and education.

Germany at the time was not yet a single nation, but rather a patchwork of small territories stitched together like scraps of colored cloth. Yet within this home, at least, the world was kept in careful order.

The spines of thick law books lining the study shelves, the scent of dark bread baking by their mother’s hand, the gentle voices drifting through the house, and beyond the window, a forest so deep it seemed bottomless. All of this formed an unquestioned reality for the young brothers.

The Father’s Death, and a Closed World of Brothers

That world, however, fell suddenly silent just as they reached the threshold of adolescence.

Their father’s sudden death.

It was not merely a farewell, but the collapse of the very center of their lives. The stability they had known existed only as long as he was there.

The moment he was gone, income vanished without a sound, and society at the time offered no safety net to take a family into its care. The life they had known could not be maintained, and reality revealed itself in the form of debt.

At eleven and ten years old, Jacob and Wilhelm were forced to shoulder responsibilities far beyond their years. With the help of an aunt, they were sent to a boarding school in Kassel. But it was a place where poverty measured a person before learning ever could.

Differences in appearance could not be hidden, and the brothers naturally withdrew into each other’s company.

They slept in the same bed, shared the same loaf of bread, and turned the pages of the same old dictionaries. The colder the outside world became, the more deeply they retreated inward, forging a bond sustained by words and silence alone. When Wilhelm later described their relationship as

“as if one soul had been divided into two bodies,”

it felt less like an exaggeration than a quiet statement of truth.

During adolescence—a season when attention would normally turn toward the opposite sex—the brothers faced not the warmth of women’s bodies, but the structures of dead languages.

It is difficult to deny that the logic and intimacy they shared, untouched by anyone else, may have created a bond stronger than most ordinary forms of love.

Jacob, who sealed his emotions tightly within himself, and Wilhelm, who sharpened his sensitivity while carrying a frail body.

Within the fragile balance of these two unequal beings, love had not yet turned outward. It remained quietly at the center of a small universe called brotherhood.

A Heat Belonging to No One, Found in a Library

From Law Shelves to Ancient Love Songs

At eighteen, Jacob enrolled at the University of Marburg. A year later, Wilhelm followed in his brother’s footsteps and entered the same institution.

Their field of study was law—the same discipline their late father had practiced.

It was almost the only remaining option for restoring their livelihood. Yet the dry language of legal codes never truly settled in their hearts.

The turning point came with their encounter with the jurist Friedrich Carl von Savigny.

Savigny did not read law as a system of rules, but as a layering of history. His lectures revealed that behind contemporary regulations lay the thoughts and emotions of people who had once lived. That perspective quietly drew the brothers’ attention away from a future profession and toward the words of the past.

What makes this moment compelling is that, despite being shaped by the same influence, the brothers responded in different ways.

Jacob sought to organize language, to grasp it as a system. Wilhelm, by contrast, was attuned to resonance and aftertone, sensing within words the presence of human lives.

The medieval poetry and love songs they encountered in Savigny’s private library were not, for them, “love itself.” Rather, they were ideal materials for understanding how emotion had been sealed into language over time.

Love, to the brothers, was not so much something to be lived as something to be read—and it was during this period that this sense of distance quietly took shape within them.

The Woman Welcomed into the Circle of Stories

A Long Love That Began with Folktales

After returning to Kassel, the brothers—immersed at university in medieval languages and narratives—began to turn their attention away from words preserved in books and toward those that still lived on people’s lips. It was then that they began collecting folktales in earnest.

During this process, they grew close to Dorothea Wild, the daughter of the Wild family, who ran a pharmacy nearby. She was known affectionately as Dortchen.

The family was well-off, and their shop—frequented by townspeople—served as a quiet gathering point for local news and conversation.

At the time they met, she was still a young girl in her early teens. She loved telling old stories and could recount them with remarkable vitality. She had received no special training; she simply reproduced, in her own words, the tales she had absorbed since childhood.

Wilhelm eagerly wrote down the early forms of “Little Red Riding Hood” and “Hansel and Gretel” as they flowed from her mouth. These were not yet polished narratives, but living folktales—stories whose details shifted with each telling, where fear and cruelty, along with a faint promise of rescue, still existed in an undivided state.

At first, Dortchen was for Wilhelm an “important storyteller,” a “precious collaborator.” But as the years passed, their relationship slowly changed in nature.

The girl grew into a thoughtful, quietly intelligent woman. Wilhelm began to listen not only to the content of her words, but also to the rise and fall of her voice, and to the silences that appeared between sentences.

Gradually, the stories seeped not only onto the page, but into the fabric of his own life.

A Curious Triangle

Nearly twenty years after their first meeting, Wilhelm—now thirty-nine—married Dortchen.

Yet their new life together differed greatly from the conventional image of a married couple. A room for his brother Jacob was, quite naturally, included in the new home.

For many years, the Grimm brothers had shared both life and work completely. Marriage did not sever that bond; it merely altered its structure.

The three lived under the same roof, shared meals, and divided their working hours.

Jacob did not stand in the way of his brother’s marriage, and Dortchen, fully aware of the brothers’ bond, chose to place herself within it.

From the outside, this arrangement may have appeared strange. To them, however, it was a perfectly natural choice.

Wilhelm’s life gained stability, Jacob’s scholarship acquired quiet continuity, and Dortchen—at the center of it all—became the one who tuned the rhythm of time flowing between the two men.

Their relationship lay far outside conventional definitions of romance.

And yet, it may have been precisely this irregular circle that sustained the Grimm brothers’ work and lives to the very end—a distinctive form of love.

Words in Motion, Bonds That Would Not Unravel

Exile and Wandering — As the Seventh Professor

At the age of fifty-two, Jacob found himself at the center of what would become known as the “Göttingen Seven” affair. Among the seven professors who protested the king’s suspension of the constitution, Jacob was one of the leading figures.

For him, this was less a political struggle than a matter of fidelity to words.

If something once promised could be unilaterally violated by power, then silence was not an option—this was the ethical line he refused to cross.

Faced with his brother’s dismissal and exile, Wilhelm chose not to remain behind. Together with Dortchen and their young children, he joined Jacob in stepping once more into an unsettled, wandering life.

Rather than weakening them, this period of uncertainty quietly strengthened the bonds of the family.

Jacob, who remained unmarried throughout his life, welcomed his nieces and nephews as extensions of his own daily existence. Between hours of scholarship, he taught them words, handed them books, and treated them at times with sternness, at times with surprising gentleness.

Even without a home, even without titles, they never ceased to be the “Brothers Grimm.”

Within that enduring circle remained the daily life safeguarded by Dortchen—and the quiet presence of small lives, watched over by Jacob with something close to a father’s gaze.

An Endless Work, an Unchanging Circle

After several years of wandering, the brothers were invited to Berlin by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia. At last, they regained both official positions and a stable life.

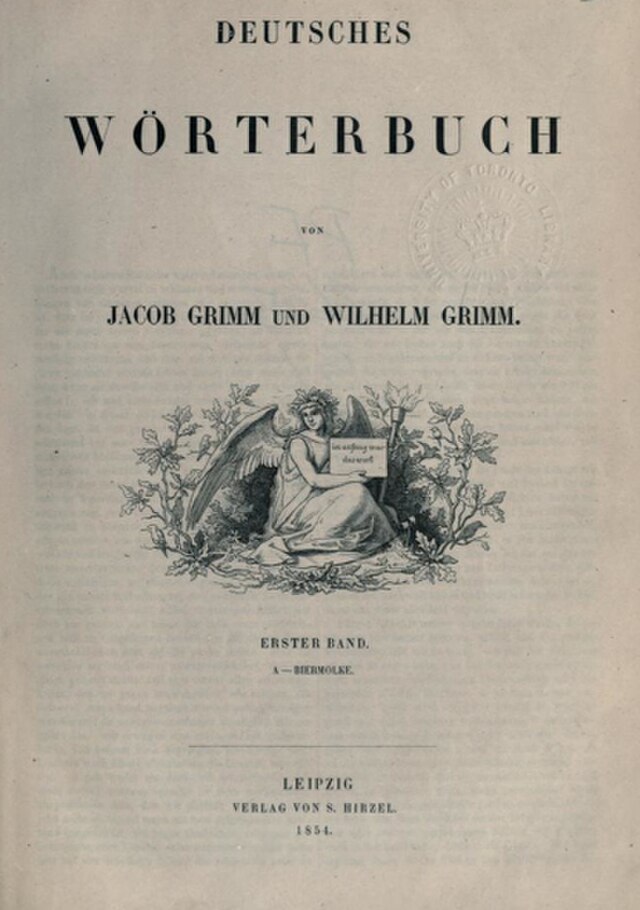

In Berlin, they were entrusted with the compilation of the German Dictionary—a national intellectual project of immense scale. It was not merely a collection of words, but an attempt to record the history of the German language itself: its origins, shifts in meaning, and accumulated usage.

From the beginning, it was clear that the work would take decades to complete. Even so, the brothers accepted the task.

Jacob remained on the front lines of research, plunging deeply into etymology and historical texts. Wilhelm, mindful of his health, continued writing, refining the prose and shaping the work into a readable whole.

Just as in their youth, the brothers sat side by side as equal collaborators.

From Scholarly Text to Fairy Tales

The first edition of the Grimm’s Fairy Tales, published when the brothers were in their late twenties, was an extraordinarily quiet beginning for what would later become a global classic.

At the time, it was not intended as children’s literature, but rather as a record of oral tradition. Critics found it too academic, too cruel, insufficiently polished as storytelling. The reception was far from enthusiastic.

The brothers, however, did not see this response as a failure. Instead, it prompted them to consider what stories need in order to live on.

Over the next forty years, the collection was revised repeatedly, eventually reaching a seventh edition. Throughout this long process, each brother played a distinct role.

Jacob focused on narrative structure, motifs, and the ancient layers of language, striving to preserve the skeletal integrity of the traditions. He was, at first, not without resistance to changes that might distort the original forms.

Wilhelm, by contrast, was attuned to tone, rhythm, and emotional flow. He did not hesitate to let the stories evolve into something meant to be read aloud and passed on.

Thus, even as they disagreed at times, the brothers rewrote each tale again and again.

“Little Red Riding Hood” was sharpened into a concise, resilient narrative; “Hansel and Gretel” gained deeper symbolism; “Snow White” and “Sleeping Beauty” settled into forms that held both terror and beauty in balance.

These were no longer mere records of collected folktales.

Through the brothers’ hands, they became “German stories”—capable of being told and retold across time and place.

That these stories now live on in children’s hands and within households, as tales told at night, is something that hardly needs to be said.

Unfinished Words

The End of the Story

In his later years, Wilhelm lived on while carrying with him the frailty that had marked him since youth.

His illness of the chest gradually worsened, and his physical strength steadily declined—yet he never left his desk.

The compilation of the German Dictionary, the revision of the fairy tales—these were as natural to him as breathing, inseparable from daily life itself.

And then, in 1859, Wilhelm passed quietly from this world at the age of fifty-nine.

It is said that his final moments were like a lamp whose flame slowly, gently faded over time.

To those around him, it may have seemed the death of a distinguished scholar.

But to Jacob, it meant losing the one with whom he had walked side by side throughout his entire life—another self.

“Half of me was buried with him.

The other half must remain here a little longer, in order to complete this dictionary.”

With those words, Jacob took up his pen once more.

The seemingly endless task of the German Dictionary was, for him, the very reason to go on living. Digging into etymologies, gathering examples, recording the histories of words—this labor was also an extension of the time he had shared with his brother.

At seventy-eight, Jacob too passed away peacefully.

His was a quiet end, close to death by old age.

Jacob’s body was laid to rest in a Berlin cemetery, beside his beloved brother Wilhelm. And nearby sleeps Dorchen as well, who departed a few years later. Even in death, they remain close, preserving that triangle unchanged, leaning gently toward one another.

The German Dictionary they began was passed down through the hands of many scholars and reached completion roughly one hundred years after Jacob’s death. It was not the work of a single person, but a long continuum of lives devoted to language.

What Was the Grimm Brothers’ View of Love?

Jacob, Wilhelm, and Dorchen.

The relationship they lived within never fit, from the outset, into the conventional framework of “one-to-one romantic love.”

For them, love was not about possessing someone, but about sharing life itself—time, daily existence, and language. In days spent telling stories, writing them down, and reading them again, the three breathed the same air, gazed upon the same world, and together built a single life.

That Jacob remained unmarried throughout his life was likely not a lack, but a choice. By welcoming his brother and his brother’s wife fully into the inner space of his own life, he lived within a relationship so complete that there was no need to seek new love elsewhere. It was a closed circle, and at the same time, a form of existence that accepted others more deeply than most ever could.

Perhaps even now, the three of them sit side by side in heaven, choosing words as they weave fairy tales together.

And beyond the page, one cannot help but imagine a slightly strange, somehow nostalgic fairy tale—one no one has ever read before—continuing to be born, quietly and endlessly.

日本語

日本語