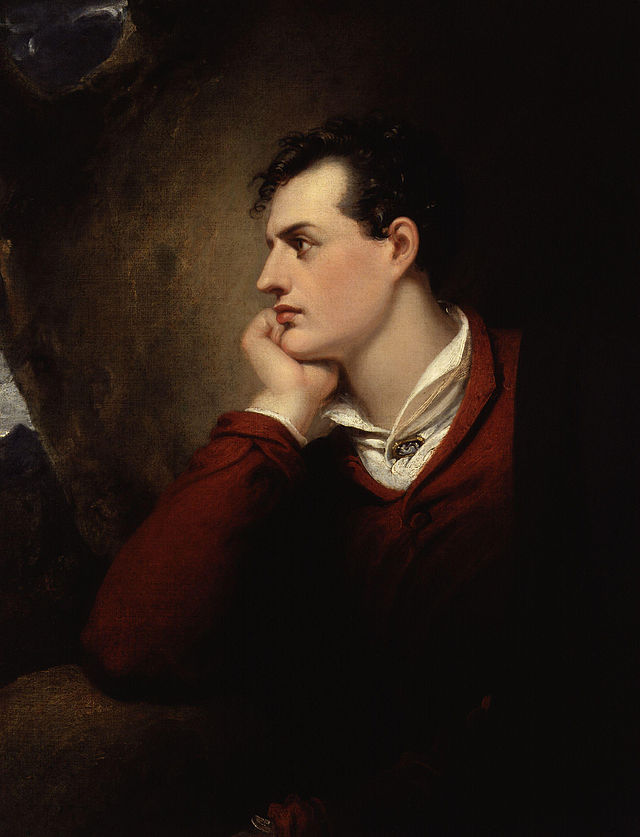

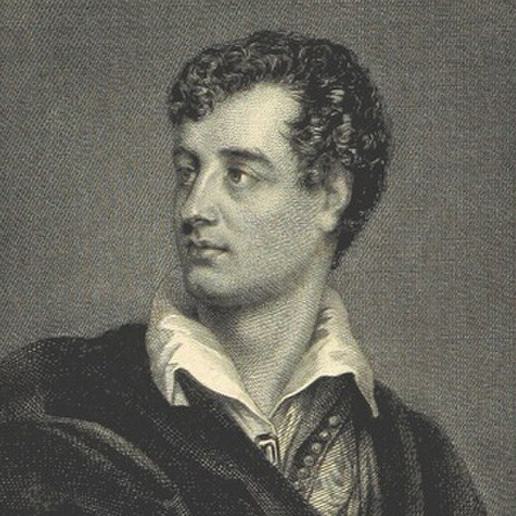

Lord Byron’s View of Love|What Drove the Romantic Poet to Dangerous Love?

In the early 19th century, when London’s fog still wrapped the city in its familiar scent, a man moved between the salons and the bedrooms of high society, armed only with poetry.

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron.

A leading figure of the Romantic movement, an English nobleman, and—so his contemporaries said—the very embodiment of the love scandal.

The success of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage made him a literary sensation overnight.

His striking features and languid gaze pierced the hearts of women across Britain without mercy.

But it wasn’t only his poetic gift that carved his name into history.

It was the loves that flared like storms, and wrecked themselves like storms.

Early Years and the Birth of Solitude

A boy with a crooked foot, trying to walk straight

Byron was born in London on January 22, 1788.

Soon after, his father died, and he moved with his mother to Scotland.

He was born with a clubfoot in his left leg, and every run left a slight drag in his step.

That gait planted both a deep inferiority complex and a fierce defiance in him.

His mother’s moods swung violently—spoiling him one moment, scolding him the next.

His young heart was restless, always seeking a place of safety.

Eventually, he found refuge in the limitless sea spread across the pages of books—literature.

The Smile of Mary Duff

At eight, in the chill sea winds of Scotland, Byron fell for an older girl—Mary Duff.

Chestnut hair, a smile that lifted one corner of her mouth just so.

That smile was like sunlight breaking through overcast skies.

He would take the long way around just to pass her on the road, saying “Hello” as they crossed.

That instant made something leap inside his chest.

Later he would write:

“Her smile was the prototype of all the happiness I have ever known.”

But happiness didn’t last. A few years later, still in boyhood, he heard she had married another man.

It felt as if a cold stone had been placed deep in his chest.

From that moment, he began to believe: love is joy, but it exists to be lost.

Cambridge and a Season of Recklessness

A dangerous awakening

At eighteen, Byron entered Cambridge. He devoted more time to observing people than to his studies.

In company, he walked tall, dragging one foot slightly, his gaze casual yet probing the depths of others.

One evening, at a small dinner party in a friend’s rooms, a married woman of twenty-seven appeared.

Pale grey eyes, and the easy composure of one who knew life well.

We don’t know what words they exchanged, but the scrape of her chair, the way she lifted her glass—these stirred something deep in the young poet.

They began a correspondence and a series of discreet meetings.

From the outside, it may have seemed only polite conversation, but behind the quiet lay nights that drew them closer together.

The glow through curtains, the breath before dawn—these never entered his poetry, but lived on within him.

From this, he gained a conviction: age and station are mere decoration in love.

If the soul desires, that is reason enough. He never let go of that belief.

Another Face

Byron’s recklessness at Cambridge was not limited to women.

He also formed close bonds with younger male students and servants, leaving in letters and poems hints of special feelings toward them.

In an era when homosexuality was illegal, he could not speak openly. Still, those around him sensed the dual nature of his romantic inclinations.

For Byron, attraction was not about gender, but about the ineffable something a person radiated—

beauty, intelligence, danger.

Fame and Scandal

In 1812, at the age of twenty-four, Byron published Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and became the darling of the age overnight.

Black hair, fine features, and a slight lameness that only enhanced his allure—he commanded the gaze of society.

From the moment of publication, letters and gifts from unknown women poured into his home.

One morning, before breakfast, he received seven proposals of love.

He took amusement in it, sometimes even pride.

But what made him a “dangerous man” was his readiness to act on his allure.

Married women, widows, young ladies—he ignored boundaries.

Love was the fuel for his art, and art was the pretext for his love.

Society watched him with a mixture of envy and suspicion.

Between Love and Rumor

The line with his half-sister

In 1813, at twenty-five, Byron grew rapidly closer to his half-sister Augusta Leigh.

She was twenty-seven, married, and the mother of three.

They had been apart for most of their lives; their reunion in adulthood seemed, at first, like pure sibling affection.

But to Byron, Augusta became more than family.

Behind his public success lay harsh criticism and mounting debt, and his mental state was unstable.

Augusta was the only family member who accepted him unconditionally.

In his letters, he called her “my only comfort” and “my dearest friend.”

Affection and dependence crossed a line, and in 1814 Augusta gave birth to a daughter, Medora.

Who the father was—no one could prove. Still, society buzzed with rumor, and his reputation undeniably suffered.

Marriage and Collapse

In 1812, at a small gathering in a friend’s home, Byron met Annabella Milbanke.

Nineteen, with perfect posture, intelligence, and poise.

Her talk of mathematics and philosophy drew him instantly, and he nicknamed her in his mind “the princess of parallelograms.”

He proposed on the spot, but she refused.

His wild reputation and mercurial nature were too dangerous for such a careful mind.

Two years later, cornered by rumor and debt, he wrote to her again.

The letter, more sincere than poetic, moved her. In January 1815, they married.

But the marriage soured almost immediately. His spending continued, and letters to Augusta did not cease.

Distrust grew, and shortly after the birth of their daughter Ada, Annabella decided to separate.

The marriage lasted only a year. The official reason for the separation did not mention Augusta, but the gossip never stopped.

In April the next year, Byron left England. Few saw him off; no footsteps followed.

He would never return.

Exile and Loves Abroad

A wanderer across Europe

Leaving London, Byron crossed the sea in search of the air of the Continent.

The heavy stares and persistent whispers of his homeland faded with each border, and foreign skies slowly unbound him.

In Switzerland, he had a brief relationship with Claire Clairmont, which resulted in the birth of his daughter Allegra. They never married, but she left a deep mark on his journey.

Eventually, he reached Venice on the Adriatic.

At a masked ball, he danced two songs with an unknown lady, then took a gondola along the canals.

The next morning, he strolled a museum with a countess; by afternoon, he was visiting a young actress in her dressing room.

Love in Venice was like fireworks—brief, brilliant, and gone.

Different perfumes lingered in his room each night, and his desk piled high with unsent letters.

The Exception of Teresa Guiccioli

The sky over Ravenna seemed to hold light even in winter.

There, Byron met nineteen-year-old Countess Teresa Guiccioli, whose dark hair shadowed eyes that never rushed.

Her marriage was purely formal. In Italy’s upper society, arranged marriages to preserve family name and status were common.

Love was not in the contract. Instead, it was socially acceptable for a woman to have a cavaliere servente—a recognized lover.

Within this custom, they met.

Perhaps their first words were only casual greetings, but with each exchange the space between them shrank.

Soon, they moved through the day’s walks and the evening’s dinners as if breathing in unison.

Byron learned Italian; Teresa learned English.

Their letters crossed like poems, forming a bridge between them.

It was one of the rare long seasons he spent with a single woman.

When Teresa’s family was implicated in an independence movement and forced into exile, Byron didn’t hesitate.

He followed her to Pisa, then Genoa.

The light through the windows and the scent of the port changed, but his time beside her did not.

In a life of chaos, this was almost his only stability.

The Final Voyage

To a battlefield for freedom

But stability could not hold him forever.

In Italy, the scent of the ancient sea returned to him.

The Greek sunlight of his youth, the echo of his own footsteps on stone streets—these stirred once more.

Across 19th-century Europe, Philhellenism—the movement to support Greek independence—was surging.

Through Teresa’s family, Byron had been drawn into politics, and now a direct appeal arrived from Greece itself.

It awakened a long-sleeping impulse.

In 1823, Byron said farewell to Teresa and boarded a ship for Greece.

As the port slipped away, the wind was cold but his mind was clear.

He knew the path ahead might shorten his life.

In the western Greek town of Missolonghi, he used his own fortune to raise troops and buy equipment.

Before he could take the field, fever struck him down.

Burning with heat, he kept saying, “It is not yet the day to set out.”

Before the spring rain had lifted, he died quietly.

He was thirty-six.

Beside him lay a sword, a book of verse, and a short letter without an addressee.

Whether it was meant for Teresa or another, no one knows.

A Boat Adrift Forever

Byron’s loves were not merely a string of affairs.

The loneliness and sense of defect he had carried since childhood had grown into a hunger to be loved, and he sought people to fill that void.

He knew how to wield his beauty, his title, and his talent like weapons.

Love was the fire that fed his art, and parting became lines of poetry.

Breaking society’s rules brought him pleasure; forbidden loves burned brightest.

In those fleeting moments, he believed, lay the proof of life itself.

So his loves were always intense, and always fleeting—illuminating all they touched, then slipping away.

Still, he never stopped searching for the next light.

That light still falls between the lines of his poems, brushing the reader’s fingertips.

Would you reach for that light yourself—

even if it could never be held?

日本語

日本語