Van Gogh’s View of Love|What Did Love Mean to a Genius Obsessed with Marriage?

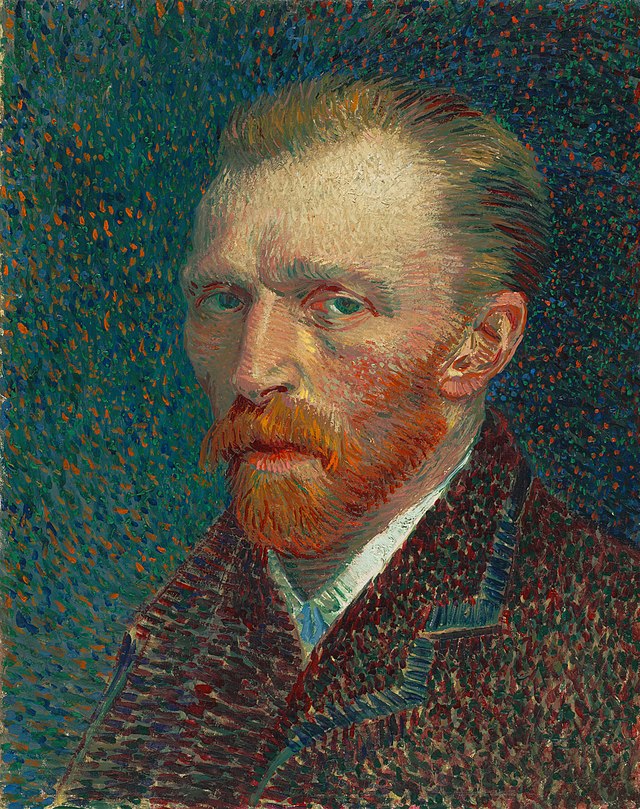

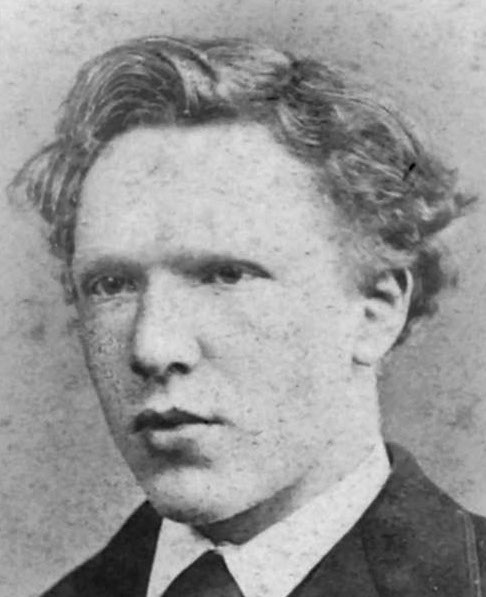

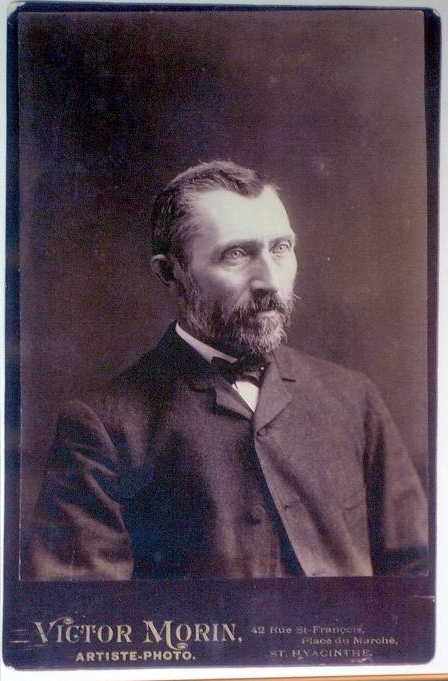

Vincent Willem van Gogh.

Though he was a painter who received little recognition during his lifetime, he is now known as a figure who left an indelible mark on the history of world art.

Brilliant colors, violent brushstrokes, and a life cut short at just thirty-seven—his story is often told as a dramatic legend of art.

In this article, however, we step slightly away from the analysis of famous masterpieces or narratives of artistic success. Instead, we look back over Van Gogh’s life from childhood to his final years, focusing on one often-overlooked theme: his view of love.

Whom did he love?

With whom did he hope to unite his life?

And where did that love ultimately go?

I hope this offers a glimpse of Van Gogh not as a mythic artist found in textbooks, but as a single human being—searching, yearning, and vulnerable.

The Town Where He Was Born

Faith and Solitude: The Origins of “Love as Salvation”

In March 1853, Van Gogh was born in the parsonage of Zundert, a small town in the southern Netherlands. His father, Theodorus, was a devout Protestant pastor; his mother, Anna, was a sensitive woman who loved drawing plants and landscapes. It was a household where religious faith and careful observation of nature coexisted.

When Vincent was born, his parents gave him the same name as their first son, who had been stillborn exactly one year earlier. This was not meant as a replacement or an act of disregard. Rather, it is thought to have followed a religious custom of the time—accepting a life “granted once again by God” as it was given.

Yet the consequence was profound. Van Gogh grew up in an environment where he could see a gravestone bearing his own name. Life and death, a chosen life and a lost one, stood side by side in his everyday world. Such an upbringing inevitably encouraged him, from an early age, to reflect on the meaning of existence itself.

Dutch society at the time valued religion, order, and stability. But precisely because of this uniformity, Van Gogh—introspective and highly sensitive—was keenly aware of how different he felt from those around him. His younger brother Theo, four years his junior, would later become his only true confidant. As a child, however, Vincent was said to be quiet, withdrawn, and prone to storing his emotions deep within himself.

A Boy Who Could Not Find His Place at School

During his youth, Van Gogh attended boarding schools and secondary institutions. At this stage, he was not studying art, nor was he drawing regularly in his daily life. He followed a fairly ordinary curriculum, learning French, English, mathematics, and other general subjects, without showing any particular academic passion.

What troubled him was not his grades, but his environment. The disciplined, collective life of boarding school did not suit his inward-looking nature, nor his tendency to internalize emotions. Teachers and classmates often regarded him as someone who “thought too much.” He, in turn, struggled to find a sense of belonging within the easy friendships of his peers.

Eventually, this sense of alienation reached its limit. Around the age of fifteen, Van Gogh left secondary school. Even then, he had no clear ambition of becoming an artist. Before committing himself to anything concrete, he was already burdened by a far heavier question: What am I meant to live for?

Instead, he immersed himself deeply in the Bible, in ideas of morality, duty, and self-sacrifice. At an age when many experience friendship and their first gentle romances, Van Gogh was already attempting to shoulder the meaning of life itself.

Perhaps it was this childhood—one in which he never learned how to gauge emotional distance from others, while his inner world grew ever larger—that later shaped his tendency in love to move too close, too quickly.

The Lodging House in London

His First Love, Unreturned

After leaving school, Van Gogh entered the large art dealership Goupil & Cie through the connections of his uncle. He worked as an art dealer while moving between The Hague, London, and Paris.

The job of an art dealer was not to paint.

It involved managing artworks, explaining them to clients, and mediating sales—in other words, acting as a bridge between art and the market. Language skills and knowledge of art were essential, and much of the work consisted of administrative duties and customer service.

During his time in London, Van Gogh met the daughter of his landlady at the boarding house where he stayed (the Eugénie theory is now considered the most likely). There was no dramatic incident that sparked his feelings. Rather, through the accumulation of everyday conversations under the same roof, he gradually came to imagine her as a future life partner.

When he finally confessed his feelings, however, he learned that she was already engaged. His love ended as a one-sided attachment. For Van Gogh—who believed that sincerity would always be rewarded—this was the first harsh reality he was forced to confront.

He continued working as an art dealer, but his performance gradually declined.

The reason lay in his personality. Instead of recommending paintings that would sell, he felt compelled to explain why a particular work was right. He prioritized discussions of art and morality over the preferences of his clients. Though his role was to sell, he had begun to lecture.

In time, his passion faded, and his path as an art dealer came to an end.

A Decision Finally Reached

After his career as an art dealer collapsed, Van Gogh did not immediately find a new direction.

For several years beginning around the age of twenty-three, he held no steady job. He attempted to become a teacher and failed, then turned to religion in search of answers, studying theology. Later, in the coal-mining region of Belgium, he worked as an unpaid missionary, living among laborers and giving away his possessions in acts of extreme devotion. Yet even this was deemed “excessive” by the church authorities, and once again he lost his place.

Having failed to find acceptance in either work or faith, the only thing left to him was a simple desire: to be of use to someone.

At the age of twenty-seven, Van Gogh finally chose to draw and paint. This decision was less a matter of confidence in his talent than a last means of offering himself to others and to the world.

A Love Met with Rejection

Choosing the life of a painter brought with it a very practical concern: how to sustain himself.

In his letters, Van Gogh repeatedly expressed his anxiety about living alone and his deep longing for a domestic life. He did not believe art and everyday existence should be separated; to reconcile the two, he felt it necessary to share his life with someone.

This longing gradually crystallized into a concrete desire for marriage.

At the age of twenty-nine, while staying at his family home, Van Gogh was reunited with his cousin Kee, who was seven years his senior. She had already been married and widowed, and was raising her child while leading a realistic, grounded life.

To Van Gogh—after years of drifting and searching for a “livable” form of life—she appeared as someone who understood responsibility as well as emotion. It is likely that he was drawn to her not simply out of romantic feeling, but because he saw in her a partner with whom he might rebuild his life through the structure of family.

Yet his way of loving did not allow relationships to develop slowly over time. The moment he felt a spiritual connection, he sought to finalize it through marriage, making a clear and direct proposal.

For Kee, this decision came far too quickly. Having already experienced the realities of life, she could not choose her future based on emotion alone.

Her reply was brief and decisive:

“No, nay, never.”

There was no hesitation, no ambiguity—only a firm boundary.

Her family also opposed the marriage. Beyond their blood relationship, they judged that Van Gogh, who had only just begun his life as a painter and had no stable prospects, lacked the practical ability to support a household.

Having lost his place once again, Van Gogh left his family home.

The realistic form of life he had been seeking was shattered by this unmistakable rejection.

The Repetition of Unequal Love

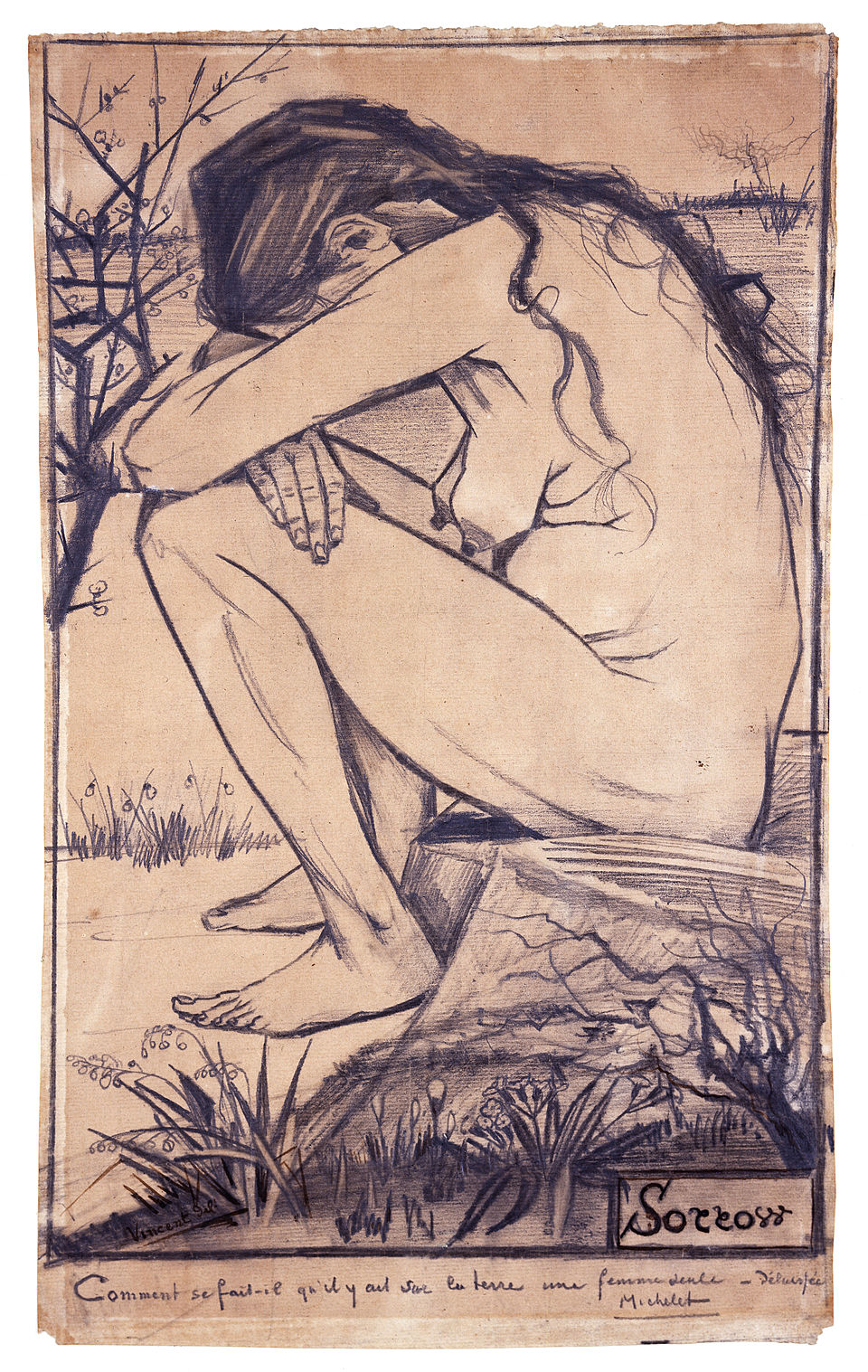

Sien, the Prostitute

After leaving home, Van Gogh moved to The Hague. One day, while walking through the city, he noticed a woman who appeared weak and exhausted. He spoke to her and offered her food and a place to stay.

Her name was Clasina Maria Hoornik, known as Sien. She was in her early thirties, had already borne a daughter, and had been abandoned by her husband. With no real options left, she had been forced into prostitution. At the time Van Gogh met her, she was also pregnant with another man’s child.

Fresh from rejection, Van Gogh was deeply affected by her circumstances. His own experience of not being chosen in love overlapped with her position on the margins of society, and he could not bring himself to abandon her.

Eventually, the two began living together.

There was certainly a physical relationship between them, but for Van Gogh this was less a romance than a life he felt obligated to take on. He tried to support her and her child, attempting to form something resembling a family. Perhaps because his earlier proposal had been rejected, he now chose a relationship that would not refuse him.

Yet this life gradually revealed its limits. Economic instability, combined with the widening gap between his ideals and reality, made it impossible both to rebuild her life and to focus on his own artistic work.

In the end, they separated, and Van Gogh found himself alone once more.

He had tried to shoulder life itself before allowing love to grow as an emotion.

The Gentle Margot

After ending his life with Sien, Van Gogh lived in Nuenen. There he met Margot, a woman who lived nearby.

She was unmarried, slightly older than Van Gogh, and led a calm life with her family. Through everyday interactions, the two grew close, and eventually their relationship developed into one that looked toward marriage.

This love, however, could not be resolved by the two of them alone.

Margot’s family strongly opposed the marriage. They believed that Van Gogh, with his unstable income as a painter, lacked the practical means to support a household. His intense and extreme temperament also appeared dangerous to them.

As the relationship stalled, Margot—caught between her family and her feelings—became mentally overwhelmed and eventually attempted to take her own life. With this, their relationship came to an end.

The quiet life Van Gogh had finally begun to grasp was once again denied by social reality.

Agostina: Where Life and Art Intersected

After moving to Paris, Van Gogh grew close to Agostina Segatori, the proprietress of the Café du Tambourin in Montmartre. While running the café, she supported it as a gathering place for artists—a woman firmly grounded in practical life.

Through her, Van Gogh found models, had his completed works displayed on the café walls, and in winter painted her portrait, The Woman of the Café du Tambourin. Their relationship began not as a romance, but as a practical trust where life and art intersected.

As the relationship deepened, however, Van Gogh once again tried to cross a line.

He proposed marriage to Agostina, but she refused. To her, Van Gogh may have been a talented painter and a regular patron, but he was not someone with whom she could share her life. After the rejection, tensions arose within the café, and Van Gogh gradually distanced himself from the place.

If Margot’s love was a gentle relationship torn apart from the outside, his relationship with Agostina was one destroyed by growing too close. It was neither a life of mutual support nor one of shared responsibility. Their inability to find a place where they could stand side by side ultimately determined the end of this love.

Here, once again, Van Gogh was forced to confront the difficulty of maintaining an equal relationship—even while standing at the crossroads of life and art.

Where Love Found Its Place

The Night the Dream of Living Together Was Torn Apart

After encountering new artistic movements in Paris, Van Gogh moved to Arles in southern France, setting his hopes on a dream: to live and work alongside fellow painters in the “Yellow House.”

For a time after Paul Gauguin arrived, the days passed in harmony. They went out together to walking paths and vineyards, painting side by side around the same models.

Yet their ways of making art—and of seeing the world—were fundamentally different. Gauguin sought to construct images from imagination, while Van Gogh staked everything on the reality before his eyes. Gradually, this difference turned into friction, and the atmosphere in the house grew tense.

Eventually, that tension erupted. With the ear-cutting incident as its turning point, their shared life came to an end.

From this point on, Van Gogh’s days would be marked by mental and physical suffering—by seizures, confusion, and instability.

Even so, he did not stop. He continued to paint through periods of treatment, and at last, long-delayed signs of recognition began to appear: high praise from the critic Albert Aurier, favorable responses at the exhibition of Les XX, and even the sale of The Red Vineyard during his lifetime.

Deep Crimson Cast Across the Wheat Fields

After leaving Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, seeking the care of Dr. Gachet. He based himself in a small room at the Auberge Ravoux and, in a remarkably short time, produced an astonishing number of paintings.

Human relationships no longer developed into romance, but his capacity for love did not wither—it simply changed direction. Wheat fields, skies, roads, houses—toward landscapes that could not answer him back, he was able to offer a quiet sincerity. It may be closer to the truth to say not that the world comforted him, but that he never abandoned the world until the very end.

Then, at the age of thirty-seven, he suddenly laid down his brush.

One Sunday evening, Van Gogh returned alone to his lodging, bearing a deep wound to his chest. The doctor judged that nothing could be done, and could only keep watch.

Soon, his brother Theo rushed to his side, and the two spent his final moments together. Among the words exchanged then, one was preserved in Theo’s letters:

“I wish I could die like this.”

It does not sound like a cry of despair, but rather carries the quiet acceptance of someone finally released from a life long held in painful tension.

At his funeral, Theo and a handful of fellow painters gathered. There was no great commotion; he was laid to rest in silence.

For many years, it was believed that he had taken his own life with a gun in a wheat field. Yet there were no witnesses, and the location and nature of the wound have led some to suggest other possibilities. The truth remains unspoken, unresolved to this day.

Van Gogh’s View of Love

Looking back on his life, his experiences in love were as intense—and as unrewarded—as his creative struggles.

An unreturned love in youth.

A proposal rushed toward marriage.

Relationships in which salvation and cohabitation became entangled.

And the repeated loss of a quiet life just when it seemed within reach.

Again and again, Van Gogh searched for a way to live together with someone—and each time, he collided with the hard limits of reality.

His view of love can be sensed in his paintings. Clear outlines, distinct colors, layers applied thickly and without hesitation—a relationship built with the same intensity and clarity. Perhaps that, to him, was what love meant.

When one looks up at the night sky over the Rhône, it is impossible not to feel it:

that his passionate love still continues to glow, quietly, even now.

日本語

日本語