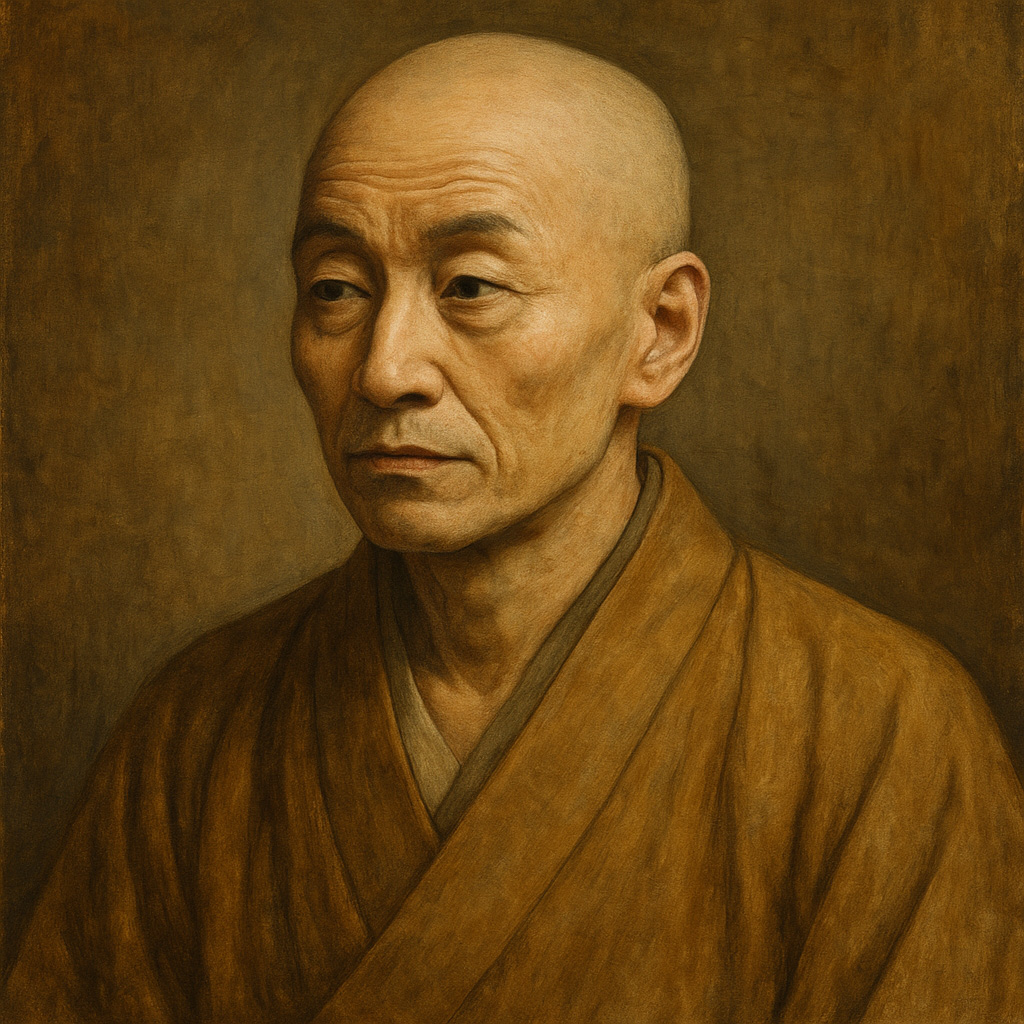

Ikkyu Sojun’s View of Love|What Truth Did the Rebel Monk Find Between Love and Desire?

On a moonlit night in Kyoto, the pale light brushed over the tiled rooftops.

Down a narrow alley walked a lone monk, a gourd in his hand and a love letter hidden in his robe—his name was Ikkyū Sōjun.

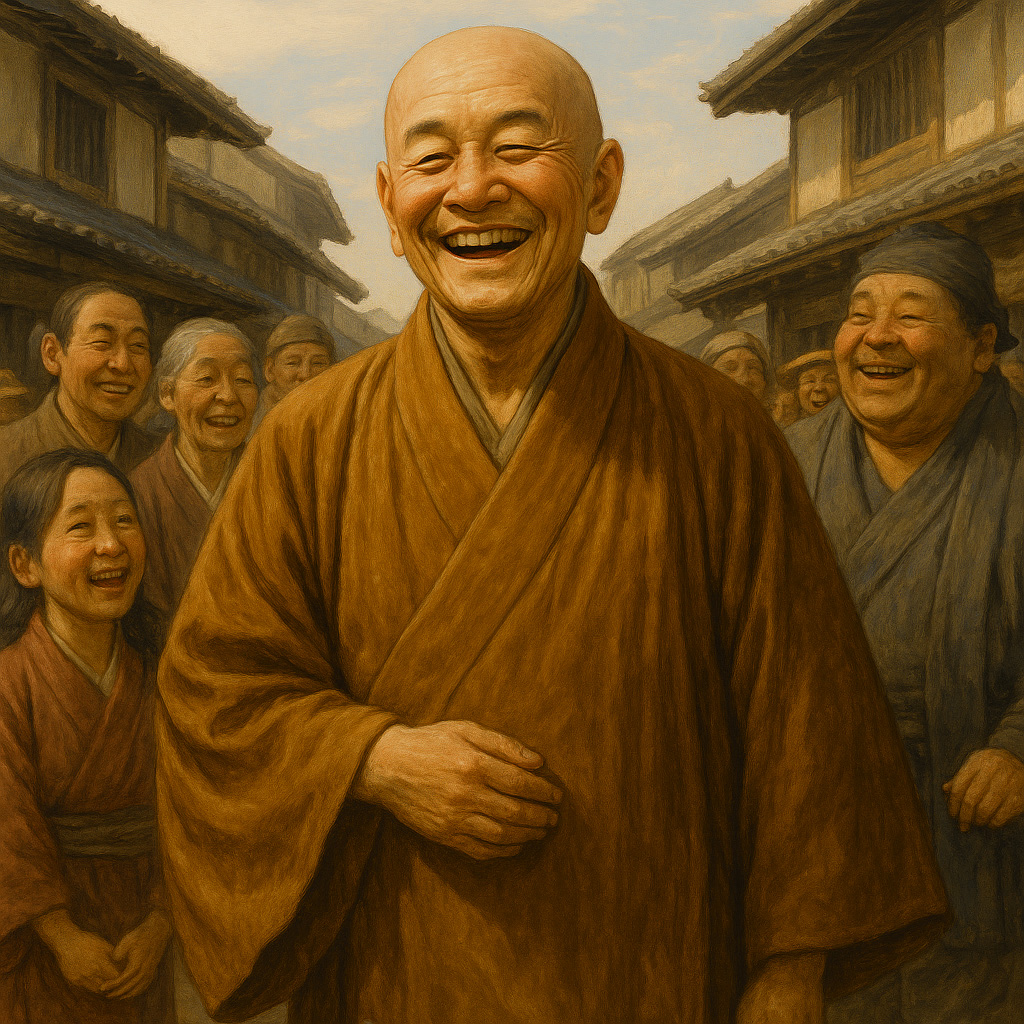

Known to many as the witty and mischievous “Ikkyū-san,” he was, in truth, a defiant Zen monk who loved wine, poetry, and women.

He left the temple behind, conversed with townsfolk and courtesans, and inscribed human warmth and weakness into his verses.

Preaching enlightenment, yet embracing desire and doubt, Ikkyū lived not as a saint—but as a man.

This article sheds light on the “view of love” held by Ikkyū Sōjun, the monk who walked the line between love and madness, seeking the quiet form of affection hidden within his unruly life.

In Childhood, Holding the Seed of Loneliness

A Nonconformist Born Under the Muromachi Sky

In 1394, in Kyoto.

There are several theories about Ikkyū’s origins, but the most persuasive is that he was the illegitimate son of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (a child born outside the lawful wife to a man of high rank).

His mother was a noblewoman of the Fujiwara lineage.

But while still young, he was separated from his mother and placed in Ankoku-ji Temple.

At the age of six, he entered the monastic life — an early parting and loneliness that cast a deep shadow on the boy’s heart.

Days of training gave him endurance and a poetic sensibility, but at the same time, quietly nurtured his longing for human warmth.

The Scent of First Love

Though there is no conclusive evidence in the historical record, it is said that in his boyhood, Ikkyū secretly admired a dancing girl he saw at a festival in Kyoto.

Beyond the high temple walls, the hem of a crimson underrobe swayed beyond the festival music.

It may have been a shock more vivid than the teachings of enlightenment.

But the precepts of a monk sealed that feeling away.

Ripening Years: Between Enlightenment and Desire

The Beginning of a Renegade Monk

In his mid-twenties, after strict training, Ikkyū attained enlightenment.

But that enlightenment was not something that severed desire.

In an age of war and famine —

the towns were full of hungry children, ruined farmland, and soldiers wagering their lives.

Having felt in his very bones the gap between the temple’s ideals and the muddy reality outside, he reached this conclusion:

“Desire is also a part of Buddha.”

Hunger for life and thirst for love cannot be discarded.

Rather, to embrace them and still smile — that is closer to enlightenment.

Not the tranquility gained by cutting off desire, but the tranquility visible when living alongside desire.

To seek that realm, Ikkyū deliberately stepped beyond the temple gates.

Before long, his steps led to unexpected encounters and to love.

Two Faces of Love: Court and Pleasure Quarters

From his thirties to early forties, Ikkyū entered the period when he lived most for love.

By day, enveloped in incense smoke at court, he exchanged waka poems with court ladies.

By night, he descended into town, visiting the pleasure quarters where shamisen music and laughter echoed.

Love at court was sustained only by words and glances.

He sought the other’s heart in a single character of a reply poem; the brush of sleeves alone could keep his chest warm all night.

Love in the pleasure quarters was more direct.

Knee to knee, tilting cups, mixing jokes and sensuality.

In coarse laughter, he would slip in a verse tinged with sudden poignancy.

His words, curiously, opened women’s hearts.

The contrast between his monk’s purity and his freedom as a breaker of rules — that was why he was loved by both court ladies and courtesans.

A love of words, and a love with body warmth.

For him, both were indispensable human truths.

Encounter with a Blind Lover

Light that Illuminates the Darkness

When Ikkyū was in his mid-fifties.

On an autumn night, at a small gathering on the outskirts of Kyoto, he was more drunk than usual.

From beyond the bustle, the soft tone of a shamisen flowed.

The sound cut cleanly through the noise and reached his ears directly.

The player was a blind woman — Shinnyo(森女).

Her voice carried a faint sensuality, and her fingers caressing the strings were quieter than the moonlight.

Fate’s meeting crept in from between the cup and the strings.

When the performance ended, Ikkyū sat beside her and touched his own cup to her hand.

People of later generations say there may have been such an exchange here:

— “Can you see the moon?”

— “I can see it with my ears.”

The truth is uncertain. Yet that one moment is warm enough to tell of the bond between them.

Between Love and Precepts

Before long, the two shared daily life and lived under the same roof.

A monk cannot legally marry —

love blooming quietly in the shadow of the precepts was rumored to be a common-law marriage.

Shinnyo set Ikkyū’s poems to shamisen music, and Ikkyū composed new songs for her.

At night, under the lamplight, they poured each other sake; before long, words ceased and silence enveloped them.

In that silence, there was undeniably the warmth of skin.

Public eyes were cold; in temple discipline, it was a violation.

Yet to Ikkyū, Shinnyo was not merely a lover, but a “reason to live” as important as enlightenment itself.

In later years, there remained a theory that one of his disciples, Giō Shōtei, was the child of Ikkyū and Shinnyo.

But as a monk, this may not have been made public, and the name may have been passed down only as that of a disciple.

Sake, Poetry, and Nightly Conversation

When Shinnyo’s shamisen fell silent, Ikkyū would always say, “One more song.”

While pouring sake for each other, they continued their exchange of poetry and music.

The blind Shinnyo caught Ikkyū’s breathing in the gaps of sound, and Ikkyū confirmed that breath with his fingertips.

It was, in modern terms, like musicians in a late-night jazz bar, improvising together while conversing through glances and gestures.

At times, sensual poetry was also recited:

“Your hair encloses the silence of the night.”

It was a verse that turned the sensation of stroking her hair directly into words.

Without dividing body and spirit, to make even touch a part of his poetry — that was Ikkyū’s way.

Later Years — The Form of Love in Old Age

The Old Monk and Shinnyo

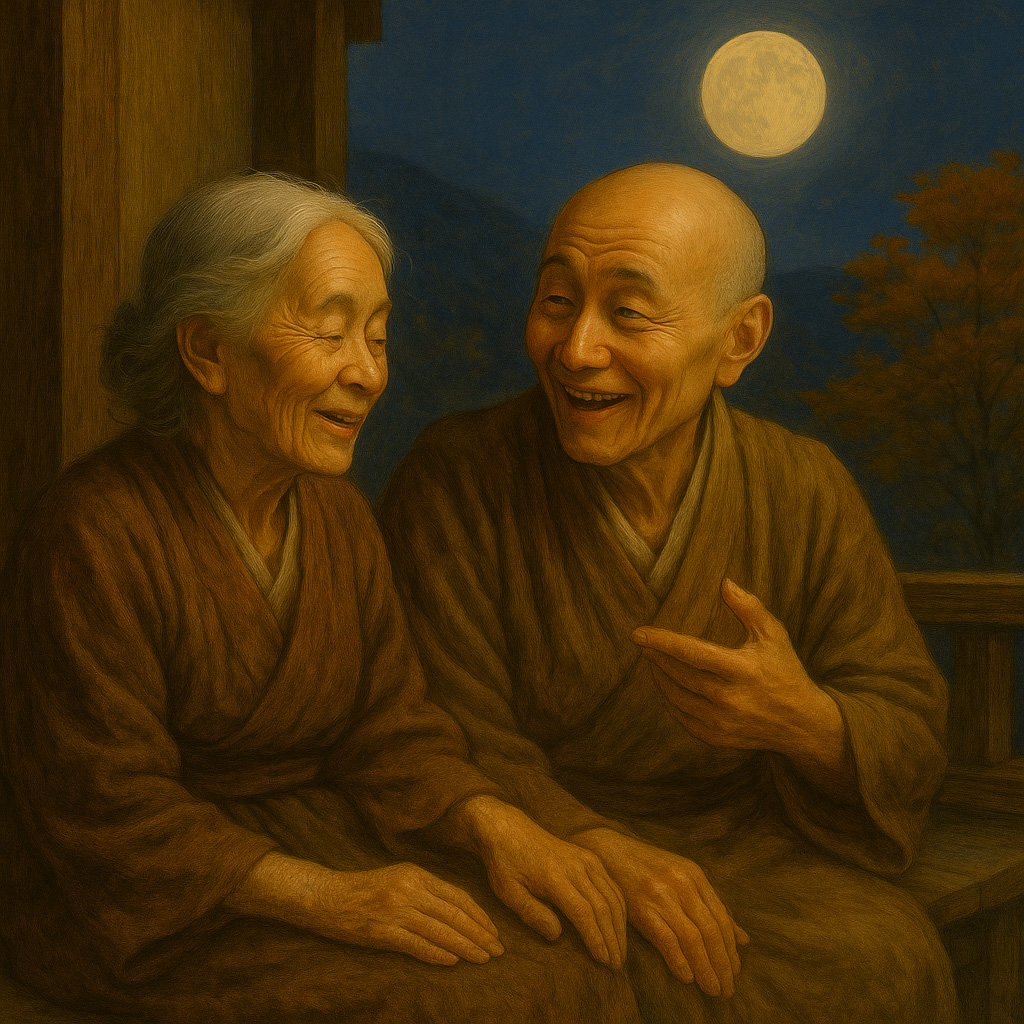

Even after passing seventy, Ikkyū stayed with Shinnyo.

Her hair turned white, and Ikkyū’s gait grew slower.

Yet the two still sat side by side on the veranda, looking up at the autumn moon.

Shinnyo, eyes closed, listened to the insects carried on the night wind and to Ikkyū’s amusing stories.

That scene was proof of a deep, calm love, different from the passions of youth.

Final Days

In 1481, Ikkyū ended his life at the age of 88.

Even on his sickbed, Shinnyo was by his side.

Taking her hand, after a long silence, he is said to have spoken:

“When it’s time to die, just die.”

As if to comfort her as she collapsed in tears, he smiled and quietly breathed his last.

To Ikkyū, love and death were nothing more than a natural flow, nothing to be feared.

A Master of Laughing Life Away with Love

What Was Ikkyū Sōjun’s View on Love?

Ikkyū Sōjun’s view of love lay outside the Buddhist precepts and public opinion.

He loved a blind woman for life and lived as if pouring desire and enlightenment into the same vessel.

For him, love was not to fill what was missing,

but the power to laugh even with the lack still there.

Love, sake, even death —

Ikkyū accepted them with a smile.

It was not resignation, but a smile of affirmation.

If you ever lose your way in love, look up at the night sky.

Under the moon, he would surely whisper:

“That’s fine. That’s just fine.”

日本語

日本語