Gandhi’s View of Love|What Kind of Love Lay Beyond His Celibacy?

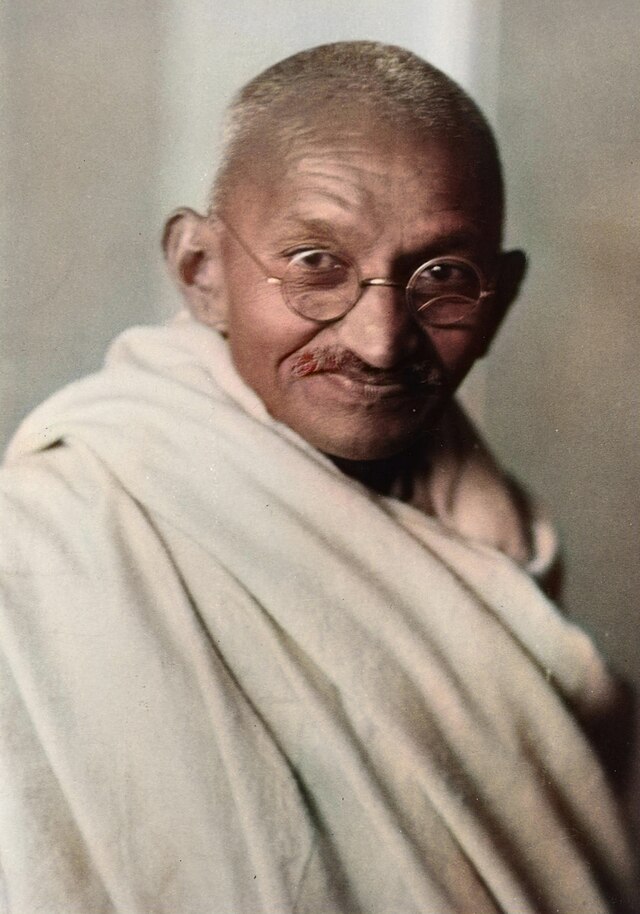

The Father of Indian Independence — Mahatma Gandhi.

By upholding nonviolence and truth, he stirred a nation through the power of conscience rather than the spilling of blood. His figure remains engraved in humanity’s collective memory.

Yet within him lived a man torn between desire and faith, love and renunciation.

This essay focuses not on Gandhi the liberator of India, but on the man who devoted his life to “loving,” “forgiving,” and “praying.”

I hope you will feel the quiet yet fervent trace of Gandhi’s heart — one rarely written about in history textbooks.

A Boy of Prayer, an Awakening of Desire

A Devout Mother and a Quiet Childhood

October 2, 1869 — in the port town of Porbandar, Gujarat, western India.

Amid the scent of sea breeze and spices, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born.

His father, Karamchand, was a local administrator, a man of duty and realism.

His mother, Putlibai, was a devout Hindu, spending her days in fasting and prayer.

If the father wrestled with the realities of politics, the mother communed with God.

Between those two poles, young Gandhi stood quietly.

Though surrounded by many siblings, he was introspective by nature.

He found it hard to express anger or jealousy, and as he watched his mother pray, he pondered what it meant to be “pure.”

Raised in a deeply religious household, he became aware early on of words like sin and desire.

The seeds of nonviolence and celibacy may have already been breathing softly in that still air of his childhood home.

A Child Marriage and Confusion Toward Sex

At the age of thirteen, Gandhi married Kasturba Makhanji, a girl of the same age.

Their families were long acquainted, and child marriages were customary at the time.

It is said the two first spoke only a few days before the wedding.

She was lively and strong-willed; Gandhi was quiet and somewhat serious.

Yet, despite their awkwardness, there must have been a faint trace of tender intimacy between them.

But sometimes the body awakens before the mind matures.

The young Gandhi soon found himself bewildered by a surge of sexual desire he could not contain.

In his autobiography, he would later write that he was “enslaved by lust” during this period —

a heat closer to passion than to love, something he did not yet know how to face.

At sixteen, Gandhi tended his ailing father day and night.

One night, when an uncle offered to take his place, Gandhi withdrew to his room for a moment’s rest and lay with his wife.

In that very moment, a knock sounded at the door — news arrived that his father had passed away.

Unable to witness his father’s final breath, he grieved deeply and later called it “the greatest mistake of my life.”

That night’s remorse and his revulsion toward lust perhaps took root as the faith that would later shape his lifelong celibacy.

The Discipline of Reason — Love as Spiritual Training

London Studies and the Art of Self-Governance

At nineteen, Gandhi left for London to study law.

Having lost his father and burdened with his family’s expectations, he sought to rebuild his life through learning.

Crossing the sea was a religious taboo, yet he swore to his mother to abstain from meat, alcohol, and women — a vow that balanced faith and future.

Back in India, his wife Kasturba quietly saw him off, cradling their young child.

There are no records of her words, but she must have felt both anxiety and pride.

In London, Gandhi was overwhelmed by the city’s liberality.

Women laughed freely, lovers held hands in public — dazzling scenes that to his devout eyes shimmered with an unsettling heat.

To avoid temptation, he buried himself in books, avoiding even the gaze of his landlady’s daughter.

In his diary he wrote:

“The conquest of desire is true freedom.”

Perhaps what he truly learned in London was not law, but how to govern himself.

Religious Practice and Discipline Through Food

As he adjusted to life in London, Gandhi grew more intent on self-restraint.

Abstaining from meat was not mere custom — it became a spiritual exercise to quiet the mind.

He joined a vegetarian society, eating with mindful awareness and believing that “to master the body is to purify the heart.”

His dietary discipline soon deepened into mental training.

He immersed himself in the Scriptures and philosophy — the Bible, the Bhagavad Gita, and Tolstoy.

Journeying between Eastern and Western thought, he began to sense that “love is found not in possession or dominance, but in patience.”

In time he earned his law degree and returned to India.

Armed with learning, he began practicing as a lawyer, yet his words carried little power and clients were few.

Confidence built on reason quietly crumbled before reality.

Still, the discipline and endurance he had cultivated in London continued to glow faintly within him.

The Power to Turn Anger Into Love

Awakening in South Africa — Redefining Love

At twenty-four, Gandhi accepted an assignment in South Africa as a lawyer.

What awaited him there was not the courtroom but the brutal reality of racial discrimination.

He was thrown out of a first-class train carriage, denied hotel lodging, and saw human dignity trampled by the color of one’s skin.

Amid such injustice, the “anger” within him slowly transformed into “love.”

Violence could not be met with violence.

If so, one must confront it with love.

Believing this, Gandhi conceived his philosophy of Satyagraha — “holding fast to truth.”

It was a new form of resistance: changing the oppressor through the power of truth and love.

For him, to “fight” meant not to hate, but to continue believing in the humanity within one’s opponent.

A Bond Beyond the Body

Eventually, his wife Kasturba and their children joined him in South Africa.

While he continued his work there, the family chose to share his life.

At thirty-seven, Gandhi took a vow of Brahmacharya — celibacy.

For Kasturba, this must have been a sudden declaration.

After years of marriage and raising four sons, her husband one day announced that he would renounce sexual relations.

Yet she did not resist.

Perhaps believing in him was itself her form of prayer.

To Gandhi, she ceased to be merely a wife and became a fellow seeker on the path of the soul.

By restraining desire together, they sought to purify love itself —

a feat sustained only by profound trust and silent understanding.

Return to India — The Practice of Nonviolence

In his mid-forties Gandhi left South Africa and returned to his homeland.

Seeing his people suffer under colonial rule, he began to live out the ideals of Satyagraha and nonviolence.

To answer violence with nonviolence —

he spoke gently, teaching the people the power of love as resistance.

His calm conviction moved hearts across the nation, and soon he was called Mahatma — “the great soul.”

Between Prayer and Desire

A Spiritual Bond With Mirabehn

While leading movements across India, Gandhi met an English woman named Mirabehn.

In her thirties, once a daughter of nobility surrounded by music and literature,

she had discovered Gandhi through Tolstoy’s writings and felt drawn to him from afar.

When they first met, Gandhi was in his mid-fifties —

a man clothed in plain white fabric, possessing almost nothing.

Yet Mirabehn saw in him a strange and radiant purity.

She adopted his ideals, dressed in white homespun cloth, cut her hair short, and became his disciple in both body and spirit.

Their relationship, though of master and student, carried a tension faintly akin to love — yet touch was forbidden.

Perhaps Gandhi saw in her devotion a form of love that transcended the physical.

An Eternal Companion

In his seventies, Gandhi led the “Quit India” movement, demanding that Britain leave India.

Amid the turmoil he was arrested, and he and Kasturba spent their final years imprisoned together.

In the stillness of the Aga Khan Palace, under limited light and air,

they shared days of prayer and conversation.

But her body had grown frail, and one winter night, in a dimly lit room, she passed away quietly in her husband’s arms.

Gandhi shed no tears, though grief welled within him.

Later he said,

“I have not lost my wife; her soul lives within me.”

For him, love was no longer bound to flesh — it was the continuity of the soul.

After that farewell, his love expanded beyond the personal, becoming a universal compassion like prayer itself.

The “Celibacy Experiments”

Soon after his wife’s death, Gandhi began what he called his Truth Experiments — spiritual tests of self-control.

He spent nights sharing the same bed with young female disciples and even his grandniece,

testing whether he could overcome sexual desire.

He described these acts as exercises of mutual trust between teacher and disciple,

yet they provoked fierce criticism.

A man revered as a saint sharing a bed with young women —

even if meant as a “pure trial,” it could not escape worldly judgment.

Still, he said simply:

“By restraining love, one comes to know true love.”

It was perhaps not an act of denial but the final stage of his quest to transcend the body while not rejecting it —

a spiritual exercise through which he sought to touch truth itself by passing through love.

At the End of Prayer

His Final Morning

In the winter of 1948, as the soft light of evening bathed the garden, Gandhi walked toward his usual place of prayer.

Clad in simple white cloth, he moved calmly through the gathered crowd.

Then, a young man pushed his way forward, and three gunshots shattered the stillness of the dusk.

The shooter was Nathuram Godse, a Hindu youth.

Ironically, it was the violence of a fellow believer that struck Gandhi down.

From his blood-stained lips came his final words: “Hey Ram”—“Oh God.”

They were not a cry of fear, but a voice of forgiveness and prayer.

As if returning all love and anger to God, that single phrase contained the essence of his life.

Gandhi’s funeral was held the next day as a state ceremony.

His body moved slowly through the streets of Delhi, while hundreds of thousands of people lined the way, offering prayers as they watched the funeral procession pass.

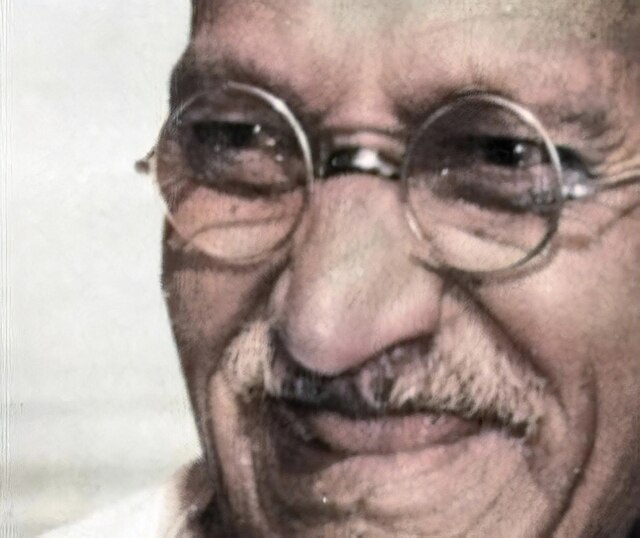

Gandhi’s View of Love

Gandhi’s life was an unending experiment in love.

Through the harsh realities of discrimination, he came to know hatred — and the power of forgiveness.

It was not only a political force that led a nation to independence,

but also an act of faith in human love itself.

To him, love was not an abstract ideal beyond the body.

Love and desire were two sides of the same sacred coin.

Thus he did not deny the body — he sought to master it from within.

Every endeavor of his was a step on the path toward truth.

Because there was love, he could forgive his enemies, guide his country, and reach out to human frailty.

For Gandhi, love began with one person and grew into a practice that embraced the world.

And you — how far does your love reach?

In loving one person, might there lie a prayer powerful enough to change the world?

日本語

日本語