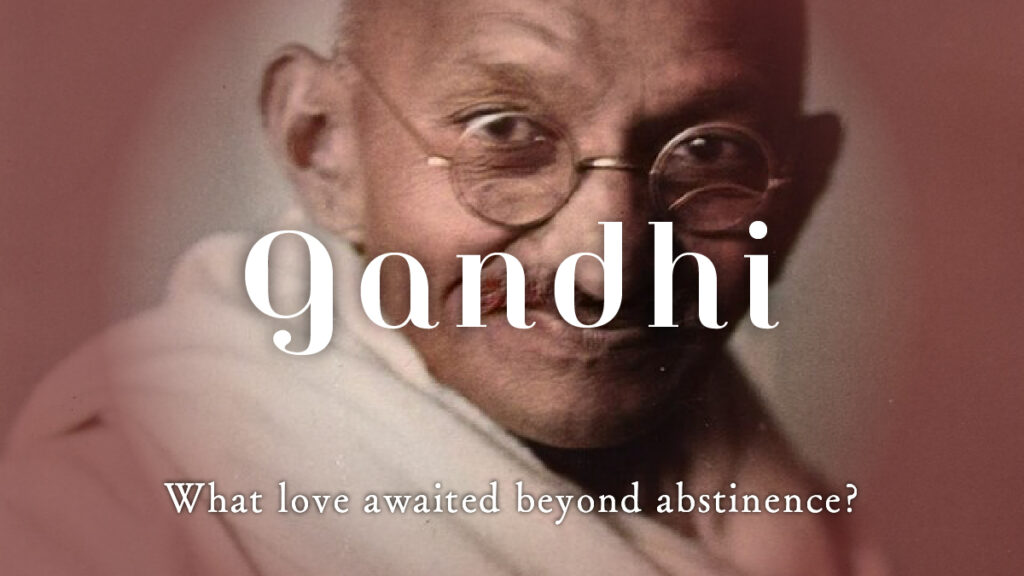

Osamu Dazai’s View of Love|What Lies Between Love and Death?

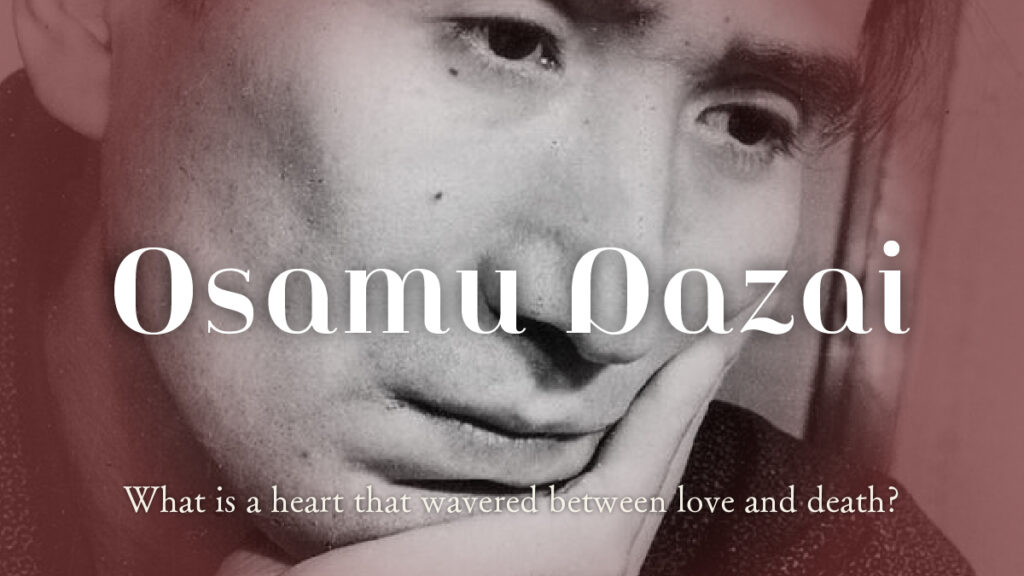

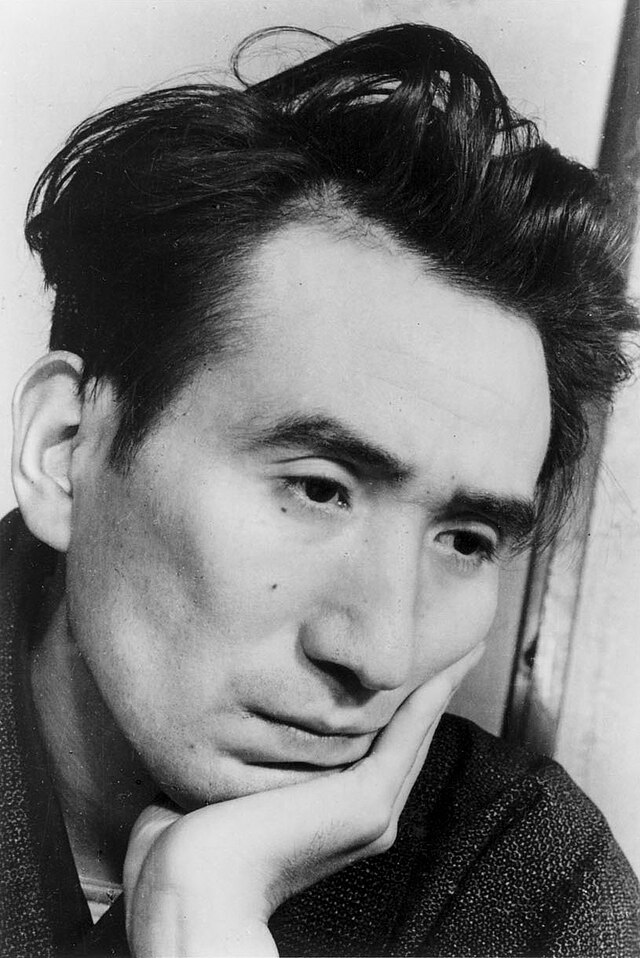

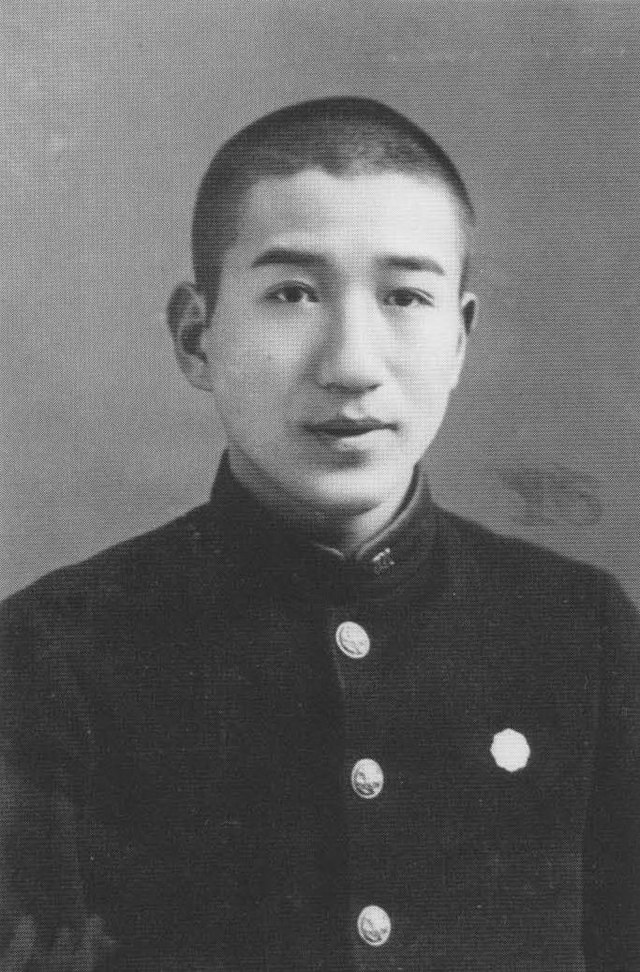

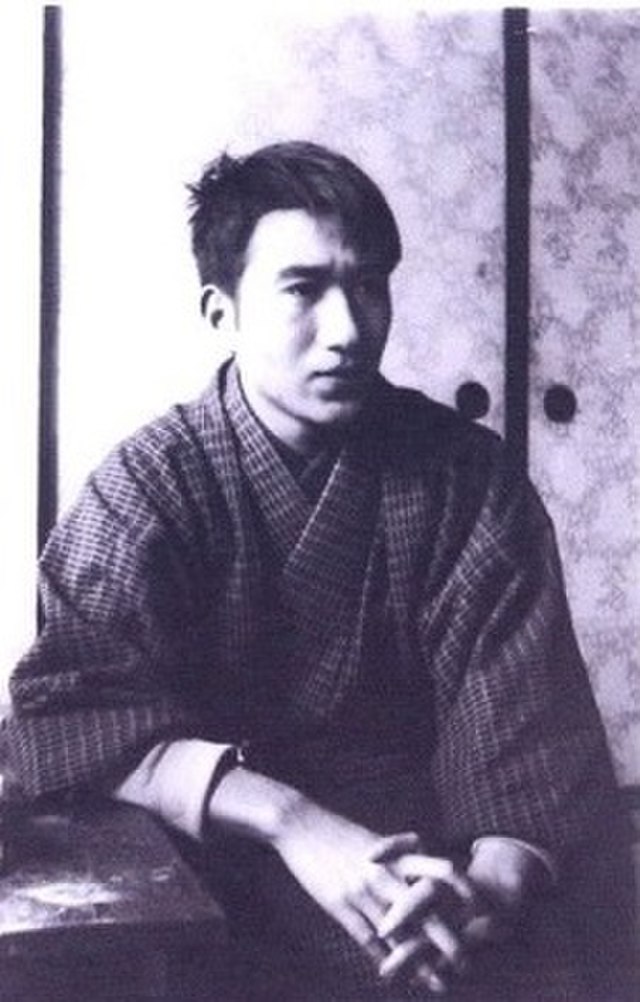

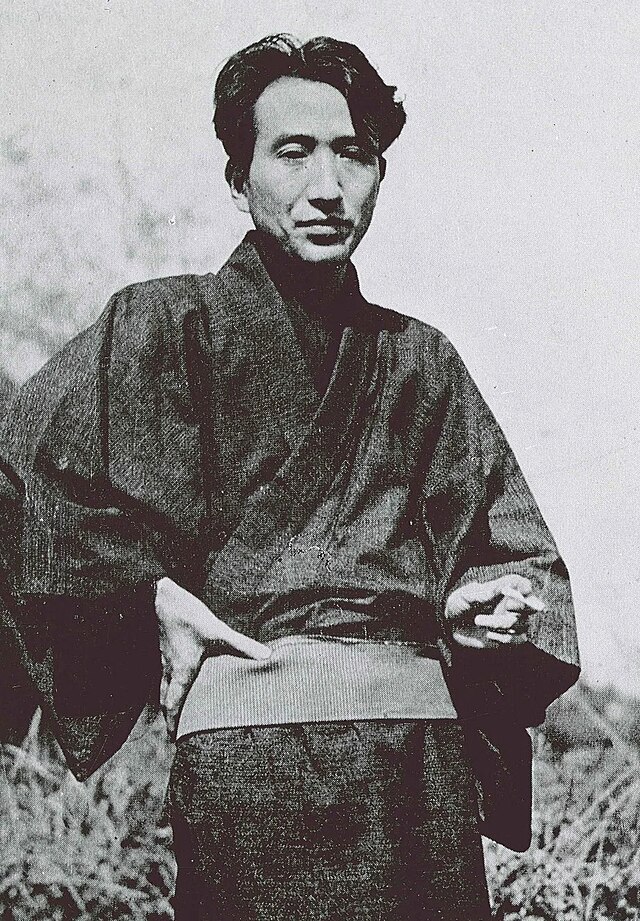

Osamu Dazai.

No Longer Human, The Setting Sun, Run, Melos! —

His works overflow with the fragility of human weakness, with a delicacy that seems barely alive.

It is as if each of his loves left behind a record of a heart slowly collapsing.

Throughout his life, Dazai encountered many forms of love — each one wounding him, yet compelling him to rise again.

For him, love may have been a small ritual of survival,

a faint act of resistance against the pull of death.

In this article, we trace Dazai Osamu’s life as the story of one man who wandered between “love” and “death.”

A Story That Began in a House Where Light Could Not Reach

A boy born into privilege

Osamu Dazai — real name Tsushima Shūji —

was born on June 19, 1909, in Kanagi, Aomori, to a wealthy landowning family.

His father, Gen’emon, was a member of the House of Representatives. His mother, Take, was frail, so a wet nurse named Kinu raised young Shūji.

The sixth son among ten siblings, he grew up watching the world from a slight distance amid a lively household.

In a home filled with political talk and business discussions, Shūji preferred sitting on the veranda, gazing quietly at the garden.

While his brothers spoke with their father about the family’s future, he listened instead to the sound of insects in the distance.

There was affection in the household — yet it somehow felt impersonal.

“To never bring shame to the Tsushima family” —

that unspoken code seemed to drift silently through the air.

Even as a child, Dazai sensed the heaviness of that atmosphere.

He later said, “I always felt like an outsider in my own home.”

The house was warm, yet somehow remote —

a strange world where kindness and loneliness coexisted.

Encountering Light and Shadow in Akutagawa Ryūnosuke

The family library was lined with political texts,

but what drew Shūji’s heart were stories —

worlds where everyone was forgiven, and even sorrow was beautiful.

In middle school, his writing talent began to shine, deepening his fascination with literature.

When he entered Hirosaki High School, he founded a literary magazine called Saibō Bungei (Cellular Literature) and began publishing poems and short stories.

For him, writing gradually became a substitute for living.

Around this time, he became captivated by the works of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa.

Beneath the intellectual, cool surface of Akutagawa’s prose lay a shapeless pain.

Perhaps Shūji saw in it the beautiful peril of exposing one’s innermost heart.

At eighteen, he was deeply shocked to read in the newspaper of Akutagawa’s suicide.

That event cast a quiet, lasting shadow over his soul.

Between Life and Death in the City of Light

Wearing a mask and walking forward

At nineteen, Dazai moved to Tokyo, ostensibly to attend a prestigious university.

But for him, the city was a place where freedom and loneliness walked hand in hand.

The buzz of Ginza cafés, the smoke of cigarettes, the laughter of modern girls —

lights unlike anything in Tsugaru enveloped him.

Amid that brilliance, he felt a faint fear:

“Here, I might dissolve and disappear.”

It was around this time that he began using the pen name Osamu Dazai.

It was a mask to create a new self,

and at the same time, a fragile skin to keep from breaking apart.

Bit by bit, Tsushima Shūji began to fade into the distance.

What Awaited at the Edge of the Sea

At twenty-one, Dazai met Shimeko Tanabe, a nineteen-year-old café worker.

Her thin cheeks cast shadows, yet her eyes were clear and bright.

They were drawn to each other at once, sharing their loneliness like two lost souls.

Though still enrolled at university, Dazai no longer attended classes, drifting between literature and vagrancy.

Dependent on his family’s allowance, his life was unstable. Some nights, he sought escape in alcohol and drugs.

To him, Shimeko’s presence was a small light that let him avert his gaze from reality.

Then one December day, the two went to the winter sea.

On the cold, windswept shore of Kamakura,

Shūji took her hand and quietly walked into the waves.

Shimeko never returned. Dazai was rescued.

From that moment on, he carried the unbearable truth of being “the one who survived.”

Why did they choose death? The answer remains uncertain.

But one thing is clear — for Dazai, love and death were twin emotions from the beginning.

To love was to soften the pain of life,

and perhaps, at its end, he glimpsed a peaceful silence.

From then on, scenes where love and death intertwine began to recur throughout his works.

The Fragile Outline of Happiness

When love turns into pain

After the incident, Dazai lost sight of any reason to go on living.

He kept on writing, but his life grew disordered; his relationship with his family had gone cold.

Writing became his only way to breathe—yet even that act itself was growing unbearable.

At twenty-six, after failing an entrance exam for a newspaper company, he tried to hang himself.

He survived, but from that point on, his dependence on drugs deepened.

Drifting somewhere between sleep and wakefulness,

Dazai gradually began to drift away from reality.

It was during that time that he met Hatsuyo Oyama, a geisha.

She was cheerful and deeply compassionate, and she sensed the delicate core that still remained within the collapsing young man.

Dazai, too, must have found some salvation in her warmth.

Eventually she became his common-law wife, and together they began a poor yet quiet life.

But happiness, for Dazai, was always as fragile as porcelain resting in his hands.

His drug dependency grew worse, and he once again attempted suicide.

Hatsuyo did her best to support him, but even her devotion only deepened his sense of guilt.

Love, for him, was both a comfort and a wound.

Within just a few years of meeting, the two chose to part ways.

It was less a breakup than an ending. Dazai could do nothing but watch her walk away.

The days with Hatsuyo were a brief respite—

and at the same time, a period that engraved upon him the difficulty of loving.

That memory of pain would later seep through his works like a lingering shadow.

The Hand Found in Darkness

After separating from Hatsuyo, Dazai’s life again descended into chaos.

Drugs consumed him; his body and mind neared collapse.

It was then that Masuji Ibuse, a fellow writer, took his hand.

Ibuse was among the first to recognize Dazai’s talent.

He gently but firmly pulled the young man back from self-destruction —

giving him a place to live, reading his manuscripts, and saying, “You have the power to write.”

Those words gave Dazai a fleeting sense of being alive again.

Ibuse became almost a father figure to him.

Through this encounter, Dazai gave up drugs and returned to writing.

In 1936, he published Bannen (Late Years).

Within it glimmered a faint light — an attempt to face life once more.

Their time together did not last long,

but for a moment, Dazai had surfaced from the depths of darkness.

Days Swaying Between Love and Reality

Meeting the light of his life

At thirty, a quiet light pierced Dazai’s long darkness.

Her name was Michiko Ishihara.

A teacher from Kōfu, gentle and intelligent,

she met Dazai through Ibuse’s arrangement. They soon married.

At the wedding, Dazai reportedly said,

“I cannot make you happy.”

It was less a vow than a forewarning.

He knew better than anyone how unstable he was.

Yet Michiko did not turn away.

As the war deepened, she devoted herself to keeping their home and supporting him as a writer.

When their daughter was born, warmth and the scent of daily life filled their home.

For a time, Dazai’s expression softened with calm.

But domestic peace was not happiness for him — it was also a restraint.

“Reasons to live” and “the urge to flee” may have coexisted within him.

Nights when his heart wandered in silence

As World War II dragged on, life grew harsh.

Publishing was restricted, paper was scarce, and censorship stripped his words bare.

Amid poverty and anxiety, Dazai lost his emotional footing.

Around him appeared various women — editors, readers, students —

drawn by the gentleness and weakness in him.

Perhaps being understood gave him proof that he still existed.

He sought salvation not in home’s quiet, but in fleeting empathy.

He was like a drifter, unable to bear reality’s weight, surrendering to momentary warmth.

For Dazai, love was not stability but escape.

Each touch of kindness drew him further from the real world.

The Longing for a Love That Would Never Betray

In 1940, Dazai published his celebrated story Run, Melos!

Known as a tale of friendship, it may conceal his yearning for “a love that never betrays.”

In Melos, who risks his life trusting a friend, Dazai may have glimpsed his ideal of love.

In reality, he betrayed his wife, blamed himself, and yet kept seeking others.

Thus, he entrusted to fiction the beauty of belief itself.

To “trust someone” was, for him, the most distant and beautiful illusion.

The Quiet Darkness at Love’s End

The Postwar Setting Sun

After the war, as life returned to the burnt ruins of Tokyo,

a woman appeared before Dazai — Shizuko Ōta, a poet.

She was simple yet possessed a curious inner strength.

She gave Dazai her diary, which became the basis for his later novel The Setting Sun.

In it, the protagonist Kazuko seeks love and rebirth amid defeat —

a reflection of Shizuko and Dazai’s own relationship.

A daughter, Haruko, was born between them, whom Dazai acknowledged.

But this further tangled his already conflicted heart.

There was Michiko, his wife, who protected their home,

and Shizuko, who bore his child —

both were love, and both were inescapable realities.

The Final Encounter

After The Setting Sun, Dazai’s relationship with Shizuko quietly ended.

Then, he met Tomie Yamazaki, a 28-year-old editor at a publishing company —

a sincere and intelligent woman.

At first, they were writer and editor,

but Tomie gradually began caring for his health and life,

and soon their silence spoke more than words.

By then, Dazai was suffering from tuberculosis and mental instability.

He had a wife, Michiko, and three children,

but postwar hardship kept him away from home for long stretches.

Tomie accepted his weakness and chose to stay by him, despite public scrutiny.

For Dazai, she may have been the mirror through which he faced himself in illness and despair.

Meanwhile, Michiko knew of her husband’s affairs yet did not openly reproach him.

In her letters, calmness and resignation coexisted.

“Please, do not stop writing.”

It was not affection, but a quiet prayer —

the kind that only one who truly understood him could offer.

The Silence Exchanged for Eternity

The Night Sinks into the Tamagawa Aqueduct

June 13, 1948.

On a rainy night during the monsoon season, Osamu Dazai and Tomie Yamazaki walked toward the Tamagawa Aqueduct in Mitaka, Tokyo.

The day before, he had left the unfinished manuscript of Good-bye on his desk.

True to its title, it became his final farewell to life.

Six days later, on June 19 — his birthday — their bodies were found in the water.

Dazai was 39. Tomie, 28.

According to police reports, the two were found embracing,

as if they had finally reached peace in death.

It was, in a sense, the purest embodiment of Dazai’s lifelong “equation of love and death.”

His wife, Michiko, accepted his death calmly.

“Even if there was a woman he loved enough to die with, I am the one he left alive.”

Her words carried not sorrow, but the quiet resolve of someone who had witnessed the life of a writer to its end.

Osamu Dazai’s View of Love

Throughout Dazai’s life, love and death were inseparable shadows.

He longed deeply for others, despaired just as deeply,

and yet still tried to believe in people.

In The Setting Sun, he portrayed a woman who lost both love and pride in postwar chaos;

in No Longer Human, he laid bare his weakness and his aching thirst for connection.

His works reveal not the salvation of love, but the painful reality of those wounded by it.

For Dazai, love was not peace — it was proof of being alive.

To yearn for someone, to wish to be understood —

in that repetition, he glimpsed the essence of humanity.

Love always broke him, and yet made him write.

It was within that contradiction that his literature was born.

Even now, Osamu Dazai’s words seem to ask us:

— Can you endure to love?

日本語

日本語